Q&A: Christine Sneed Discusses Her Compelling Story Collection About the Lure of Fame

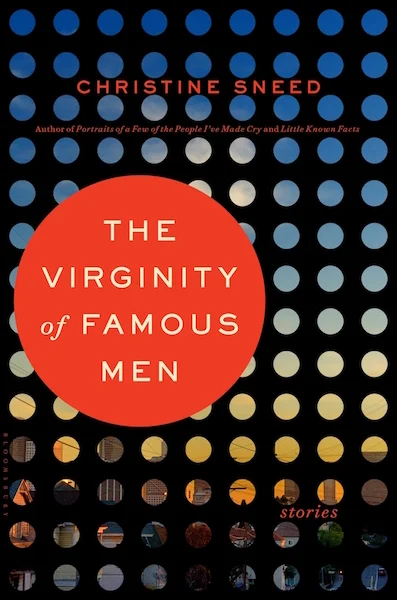

/Who we fall in love with, and why, has always fascinated Christine Sneed. In her new collection of stories, The Virginity of Famous Men, she also delves into why some of us are so drawn to fame—and how much we are willing to give up for a little bit of it.

I first encountered Sneed’s fiction when the owner of Prairie Lights Books in Iowa City, Jan Weismiller, pressed a signed copy of Portraits of a Few People I Have Made Cry into my hands. I am often grateful that she did. That book, Sneed’s first, is full of substantive, unusual stories with characters caught in messy situations, like quasi-prostitution, to stay alive.

One story in the collection — “Quality of Life” — was chosen by Salman Rushdie for Best American Short Stories, and the collection itself won the John Zacharias award for first fiction from the literary journal Ploughshares; it was also a finalist for the Los Angeles Times fiction prize. I found myself stopping to think about each story for days after I read it, turning over the extraordinary situation it detailed in my mind.

Since then Sneed has also published two novels in close succession—Little Known Facts and Paris, He Said—and now her highly anticipated story collection, The Virginity of Famous Men. -- Aviya Kushner

Q: Let’s start with the fabulous title of your new collection The Virginity of Famous Men. What is the story behind the title of the book? It looks like it was originally the title of another short story of yours, not included in this volume.

A: When this collection was acquired by Nancy Miller, my editor at Bloomsbury, it was titled The Virginity of Famous Women, but the story with that title was more like an essay, and my editor and I agreed that it didn’t complement the other stories in the manuscript. Ultimately, I also preferred The Virginity of Famous Men for the collection’s title. I wrote the first story with that title about 12 or 13 years ago, but it wasn’t the right fit for this book either.

In the end, I wrote what became the title story of this collection last August and September, and it picks up about a year and a half after where my first novel, Little Known Facts, leaves off.

Q: Many of your stories in both your collections — The Virginity of Famous Men and Portraits of a Few People I Have Made Cry — are about what M.F.K. Fisher called “the many visages of love.” (The phrase appears in “To Feed Such Hunger” in The Gastronomical Me, one of the great essay collections of all time, on page 68 in the paperback. But I digress.) What draws you to love as a subject?

A: The people we fall in love with, and in some cases, make a life with, are such an elemental part of our identity and the course our lives take—whether our lives will be mostly happy or turbulent, whether we will have exhilarating adventures or stay quietly home. I find the subject deeply thought-provoking and inspiring. Romantic love also tends to bring out the best and the worst qualities in a person—very good material for a fiction writer.

Q: In several of the stories here, the characters know they are in a hopeless situation, and yet they stubbornly refuse to change course. In the opening story, a woman nags her teenage son during a trip to a beach resort, and worries that he has become a bad person. But it is she who is increasingly out of line, culminating in a slap on the face, from mother to son, that will certainly be remembered. And in another, a 47-year-old, twice-divorced man with two children somehow stays with a 21-year-old woman he met in Mexico who he knows doesn’t love him, and is almost definitely using him. What is it about people who keep hoping for what they want against all evidence to the contrary that attracts you as a writer? Why are bad choices such great material?

A: If you don’t have the flaw, you don’t have much of a story. I see the narrative arc of a story as a series of decisions made by the main character(s), and some of them must be bad decisions in order to create the tension the story needs to keep a reader engaged and the plot moving forward.

I think it’s also a survival instinct for people to be hopeful and to keep hoping even when it’s very likely that events are not going to go the way they want them to. This optimism/foolhardiness is also a part of the American character that I think the rest of the world regards alternately with scorn and admiration.

Q: It’s hard to miss the role of fame in this book. In the story we just discussed, the gorgeous and poor young woman will clearly do anything to be famous. She swiftly moves from Mexico to America with a man she just met, leaving her family within minutes. In another story, a relatively normal professional woman finds herself, to her own surprise, married to a famous actor, shortly after her marriage proposal arrives — in front of the entire world, on television. In this era when the lines between private and public are blurring, when internet celebrity is making “fame” easier to get than ever, and when a single comment on Twitter by an average citizen can go viral, it seems that the definition of “fame” is changing rapidly. Why did you want to write about fame? What do you think it is about fame that makes so many people want it so desperately?

A: One thing that I attempt to do in some of my stories is examine the myths that Hollywood and celebrity culture have been very successful in marketing and selling to most of the world. Fame and wealth are glittering dreams, but like all dreams, they’re insubstantial, and also, in as many cases as not (probably many more than not) the realities of being rich and famous poorly translate to real life. What you think you want isn’t what you actually get, etc. You don’t need to spend much time Googling to find an example of a famous person whose fall from grace was well-documented and gleefully, meanly celebrated by supposed fans and other detractors lying in wait.

The contradictions in human character, like our flaws, are very good material for a fiction writer. When I taught college composition and rhetoric courses, my students and I looked at various dualities in America—for example, the fact our country’s roots lie in Puritanism but pornography is now annually a billion-dollar industry. Similarly, we want to be famous, but we also want to be left alone and never criticized for our public behavior, our mode of dress, the people we keep company with, etc.

Q: There’s also some interesting social commentary on money and its role in our lives in this collection. In “The Couplehood Jubilee,” an unmarried woman with a longtime live-in boyfriend tallies up all she has spent on friends’ weddings over the years. The total -- $24,900 -- astonishes her. The story also touches on the different economic fates of longtime friends. I notice that you’ve also written some nonfiction about money, with a piece for The Billfold on the financial life of a writer. (It’s a wonderful piece titled “Publish a Book and Change Your Life….Or Maybe Not.” Here is the link. What do you think attitudes toward money can reveal about character? And why is money a wonderful subject for fiction?

A: Your relationship to money, like the person you choose to make a life with, is a big part of who you are. Are you generous, stingy, a compulsive spender? Do you try to cheer yourself up with retail therapy instead of a brisk walk or a favorite movie or book? I saw a documentary not long ago made by Tom Shadyac, I Am, in which he interviews various scientists and philosophers about why (among other topics) we’re such a violent, unhappy species. One of the people he spoke with, an expert on indigenous cultures, I think he was, said something I can’t forget—that the accumulation of more goods than a person could possibly use was once considered to be a manifestation of insanity.

The accumulation of vast amounts of the world’s wealth by a microscopic portion of the population should be as troubling to us as most anything else that is currently plaguing us, but it isn’t being remedied at all because so many of the people making our laws and governing us are in this tiny club of Haves.

Q: I have sometimes heard fiction described as “radical empathy”— as the full imagining of another person’s life. I thought about that description while reading “Five Rooms,” in which a mother tries to teach her daughter empathy by sending her to help a blind man who was once her colleague, before he went blind. But it becomes clear that the mischievous and endearingly honest teenage narrator — who got caught throwing pennies on mall shoppers from on high — already has a big heart, and a good sense of who is worth caring about. What are your thoughts on whether it’s possible to teach someone to be more decent? Does literature have any place to play in the project of empathy?

A: I really do think that reading literature, literary fiction, and poetry especially, will make you a better person. One thing literature does is offer you access to points of view and consciousness different from your own. Most of us associate with people who are similar to us, in regard to class, education, and hobbies, especially once we’ve reached adulthood. We choose our friends based on these similarities, and our jobs also habitually bring us into contact with people whose backgrounds are similar to our own. (We wonder why America is such a polarized country?) Most of us don’t speak a second language, and the majority of Americans rarely, if ever, travel abroad; our cities and schools are deeply segregated, and we don’t actively seek out communities and people with lifestyles and opinions different from our own. What hope is there other than to teach someone to read ambitiously and with curiosity? It’s something we should all be talking about, and furthermore, encouraging every American to make a habit. Even as I type this, I’m thinking, “Good luck. Yeah, right.” But it’s more necessary now than ever before.

Q: Let’s switch gears a bit, and move from subject matter to form. One story here is in the form of a CV—but everything in it is true. It’s a classic case of “too much information.” Where did the idea for the form of that story come from? And how does it relate to the collection’s exploration of appearance and reality, deception and saddest of all, self-deception?

A: I can’t really remember what triggered it! But I do know that I was thinking about how job interviews require you to put a pretty face on all aspects of your character, and employers don’t know who they’re hiring, nor do potential employees know whom they’ll be working for, until well after the offer has been made and accepted. We spend so many hours at our jobs, and it has always seemed a harsh fact that as often as not, we don’t like some of the people we have to spend years of our lives pretending to get along with. I’m thinking specifically of office jobs. There’s a reason why Dilbert and the movie Office Space are so popular — all that time in a little warren of petty rivalries and absurdities, and of course you’re going to go a little cuckoo after a while.

As for “The New All-True CV” and the rest of the collection, I do think that, as I mentioned in reply to your earlier question, one of my main preoccupations as a writer is try to figure out why we’re so often fooled by our desires—why do some things strenuously sought after, once obtained, disappoint us? I think the Buddhist saying “The goal is in the path” offers a clue: the quest is more of a reward than the prize itself.

Q: Lastly, I’m curious to hear your thoughts about stories themselves, as a form and as a lifelong pursuit. I remember reading Alice Adams’s introduction to a Best American Short Stories anthology where she wrote: “I am deeply enamored of the short story.” I get the sense that you are deeply enamored too, that you will always write stories even as you publish novels. So I hope you can help make the case for what is wonderful about stories, and give us a glimpse into why you keep returning to them. What can short stories do like no other form? Why do you love them as a reader and as a writer? And as a bonus: what are some of your favorite stories of all time?

A: The compression of a short story, like that of a poem, is something that I find very appealing. It’s often said that writing fiction requires the ability to be a world-builder, and this challenge, i.e., the task of creating characters and their environment from nothing but an initial, triggering idea, is one that I haven’t yet tired of and hope I never will. The best short stories can take you directly into the crucible of someone’s private heart and often will show you something about your own life in only a handful of pages.

Some of my favorite (recent) short stories are Karen Brown’s “Unction,” Anthony Varallo’s “When the French Girls Came,” Karin Lin-Greenberg’s, “The Half and Half Club,” Peter Orner’s “Pampkin’s Lament,” T.C. Boyle’s “The Night of the Satellite,” Edward P. Jones, “A Rich Man,” Mary Gaitskill’s “The Girl on the Plane,” Deborah Eisenberg’s “What It Was Like, Seeing Chris,” Angela Pneuman’s “All Saints Day,” and Maura Stanton’s “Oh Shenandoah.”

Gur Salomon

Aviya Kushner is the author of The Grammar of God: A Journey into the Words and Worlds of the Bible (Spiegel & Grau/ Random House), a National Jewish Book Award finalist, a Sami Rohr Prize finalist, and one of Publishers Weekly’s Top 10 Religion Stories of 2015. She is an associate professor of creative writing at Columbia College Chicago, a contributing editor at A Public Space, and a Howard Foundation Fellow for 2016-17.