REVIEW: Two Adventurous Women Who Mapped the Botany of the Grand Canyon in 1938

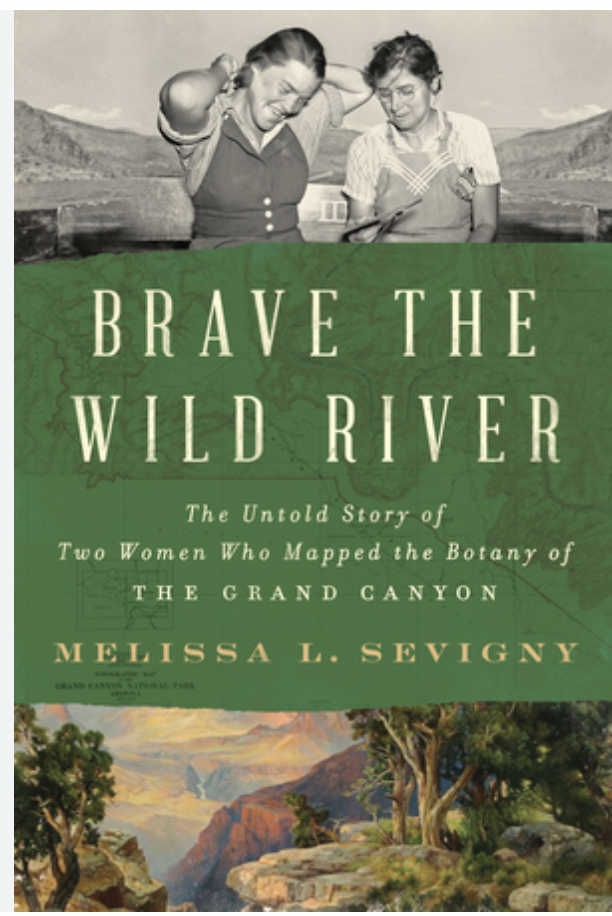

/Brave the Wild River: The Untold Story of Two Women Who Mapped the Botany of the Grand Canyon by Melissa L. Sevigny (W. W. Norton)

By Ann Fabian

It’s been a scorching summer in the Grand Canyon and a dangerous one for hikers and boaters. Park rangers have rescued overheated and dehydrated tourists, reviving them with steaming bowls of ramen and reminding them that temperatures at the Canyon’s bottom are no cooler than along its rim.

But even with climate heightened risks, the beauty of the Canyon pulls record numbers of visitors. They follow old trails left by the region’s indigenous peoples and maps designed by generations of explorers. If they brought along a copy of Melissa L. Sevigny’s Brave the Wild River: The Untold Story of Two Women Who Mapped the Botany of the Grand Canyon, they could picture a Colorado river that some locals once labeled the most dangerous river in the world.

Sevigny’s book adds two University of Michigan botanists to the roster of explorers. In the summer of 1938, Elzada Clover, a 43-year-old instructor in botany, and Lois Jotter, a 23-year-old graduate student working on a thesis on evening primroses, boated down the Colorado River—the first two white women to make it all the way from the Green River in Utah to Boulder Dam in Nevada. With a changing cast of boatmen, Clover and Jotter moved down the rivers, running the rapids and, more important to them, collecting and pressing the intrepid flora and thorny cacti, creating an essential botanical record of a fast-changing region.

The trip caused a sensation that summer. Breathless reporters reminded readers that as far as they knew only a dozen expeditions, with just over 50 men, had successfully traversed the Grand Canyon by boat. The one woman who had tried, Bessie Hyde, had vanished on her honeymoon in 1928.

Clover and Jotter had come to botanize—not for publicity and not to honeymoon. On countless occasions, they tried to explain the work that inspired the trip. But stories kept turning back to the fact that they were women—their gender more interesting than their work. They set up camp, cooked, went to the beauty parlor and made up their faces before they posed for photographers. Reporters forgot to mention botany.

Sevigny has not forgotten the plants. She writes beautifully about the geology and botany of the Grand Canyon and the challenges Clover and Jotter met as they collected and preserved the extraordinary region’s plants, the cacti, “the least demur of plants imaginable, all showy blossoms and spines.” In a couple of striking passages, Sevigny conjures the agency of plants growing in the harsh terrain. Plants “squat sullenly,” “beckon moths,” stick their spines into fabric or fur, stretch arms skyward and the challenges of the habitat. “Tucked here and there, hunkered under boulders or clinging insecurely to scree, were plants that had learned, somehow, to thrive in this place. They wove a thread of pale green around the river’s strong blue cord, hitched to the rhythms of drought and flood in ways that botanists had only begun to perceive.”

Sevigny’s artful account follows the crew along the river. She draws from descriptions in journals kept by Clover and Jotter and by their boatmen companions—Norm Nevills, Don Harris and Dell Reed—and from the correspondence left by the touching figure of Buzz Holmstrom. Using the diaries is a wonderful stroke and provides a sense of danger and uncertainty in a story whose outcome, of course, we know.

Those journals have also given Sevigny a sharp appreciation for her characters—with all their aspirations, faults and flaws. She lets us see the world through their eyes, and we root for them. But the book does something more, as Sevigny weaves histories of the Havasupai people, of exploration, botany, geology, conservation, ecology, hydrology, tourism, publicity and movie making through her account of Clover and Jotter’s trip.

And then there is the fate of the river itself, a story that haunts the whole account. Clover and Jotter ended their trip at Lake Mead, the reservoir rising behind Boulder dam, the first of the dams built to tame the wild river and provide water to the farms and cities of the water-guzzling states of the west.

I liked this book a lot, but its title sent me down a side canyon of “untold stories.” Publishers have slapped that title on books about The Grateful Dead, the Eagles, the Battle of Shiloh, the Vatican, India’s Partition, psychiatry, Marvel Comics and milk, Roosevelts, Kennedys, art thieves, kidnappers and murderers. And on dozens of books about women—women flying planes, cracking codes, fighting wars and manning newsrooms. Adding Sevigny’s good book to the list of untold stories left me wondering just where unheralded women will turn up next.

Ann Fabian is a cultural historian.