REVIEW: The Erotic Noir Novel 'The Rope Artist' is a Surreal Tsunami of Sex, Politics, Religion, and More

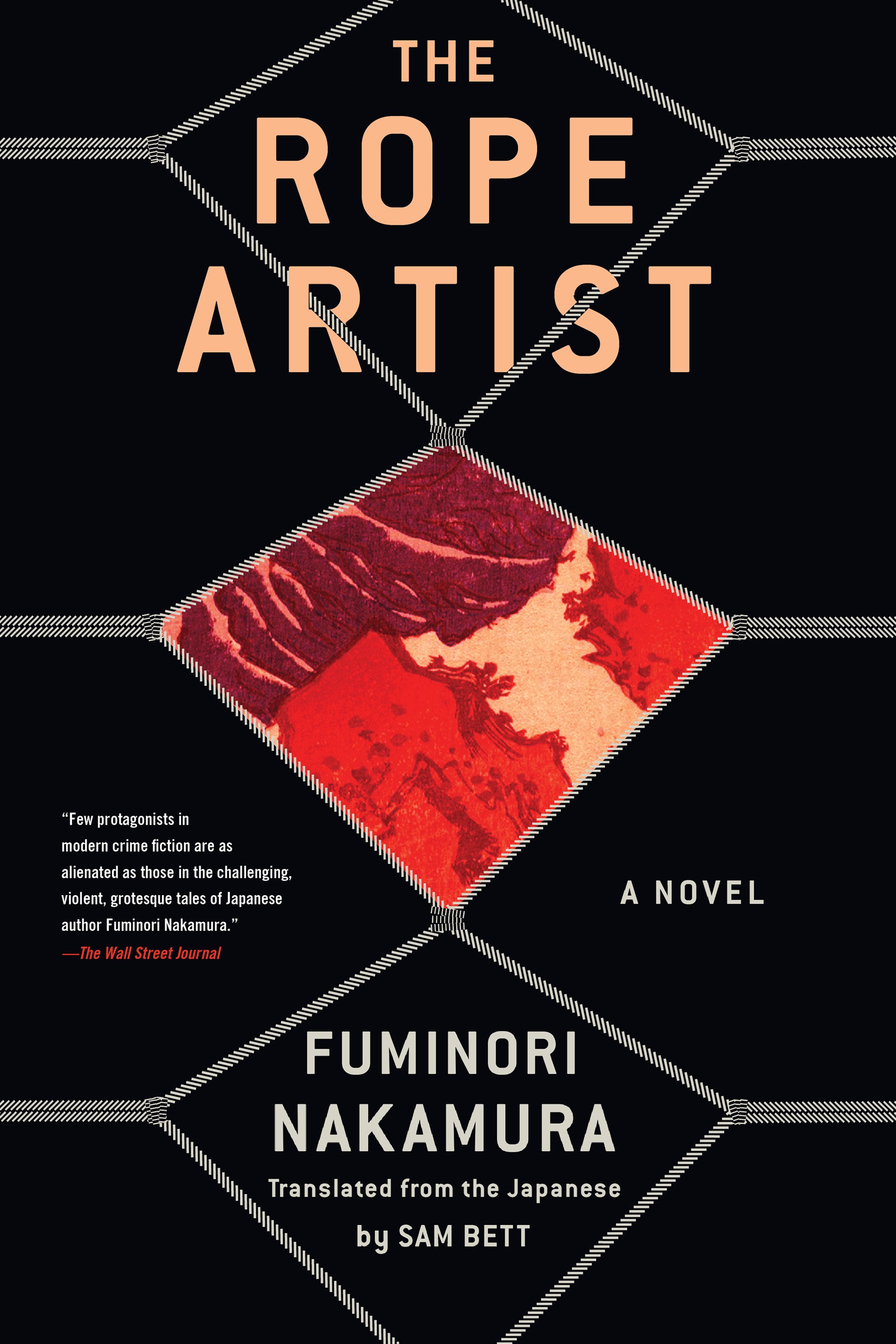

/The Rope Artist by Fuminori Nakamura, translated by Sam Bett

Soho Crime, 288 pp.

By Robert Allen Papinchak

Shake the “snowglobe of unrealistic obsessions” of award-winner Fuminori Nakamura’s erotic noir novel, The Rope Artist, to churn up a surreal tsunami of sex, politics, religion, imperialism, and haunting memories.

Propulsive prose energizes the graphic exploration of the lurid BDSM underbelly of Japanese fetishism with a challenging convoluted double-edged police procedural upending the mystery genre into an absorbing mind-bending psychological thriller.

Nakamura’s honors include the Agutagawa Prize for rising stars and the prestigious Kenzaburo Oe recognition for the slim, impressive expose of an adept pickpocket, The Thief, (translated, Satoko Izumo and Stephen Coates). Other novels from Soho Press are the expansive Cult X, the haunting The Boy in the Earth, The Gun, The Kingdom, My Annihilation (translated respectively by Kalau Almony, Allison Markin Powell, Allison Markin Powell, Kalau Almony, Sam Bett) and more.

This time, Nakamura’s clever narrative structure divides the novel into two parts, each built around the first person voice of separate detectives enmeshed in the same spellbinding crimes. He transcends the obvious salacious nature of the story line by dwelling on their distinctive personalities and modus operandi.

The first detective, Mikiya Togashi, is overwhelmed by a primal scene that dominates his memory. A “kind stranger” saved his young life by scooping him out of the abyss of a whirlpool after he was certain he had seen a woman whose “bony fingers” clutched at her bathing suit. Or perhaps it was a fantasy.

The image reappears frequently as if “memory eclipsed [his] consciousness” and surfaces as he examines the body of Kazunari Yoshikawa, victim of a brutal bludgeoning. The investigation becomes personal when he comes upon evidence (a card and an eyelash blackened with mascara) that incriminates Maiko Kirita, an escort he met on a whim at a performance club. She has been confined by Yoshikawa for several weeks.

Nothing is simple about the case. Yoshikawa was a prime practitioner of “real kinbaku,” an “intense form of embrace” with a mutual communication between a rope artist who has to predict where a “woman wants to be tied up, or how she thinks she’s going to be tied up next, to keep her feeling surprised.”

The routine inquiry becomes complicated when Togashi and the second detective, his partner, the forthright Yuichi Hayama, discover that Yoshikawa--as they know him-- does not exist. His driver’s license is fake. Enter femme fatale number two, Ami Ito. She, too, had lived with “Yoshikawa” until she was found hanged during another investigation.

For the remainder of the first part of the novel, Nakamura plays an adept cat and mouse game with the reader, exploiting every avenue of deception. Once Togashi exits the novel (and it would be a major bombshell spoiler to reveal how and why), Hayama takes over as narrator and there is a seismic shift in the plot.

A sex tape with Maiko and Togashi emerges sparking suspicions that the duplicitous Togashi may or may not have been involved in Yoshikawa’s murder. Police work begins to take place “on the edge of darkness.”

It’s here that Nakamura introduces the compelling social and cultural background of kinbaku, its history and its mythology that reaches back to the Edo period in the time of the samurai. At first, police used knots to tie up criminals until “over time, a bunch of different styles appeared, so they could switch it up depending on the crime and the social standing of the criminal.” People saw it as a “form of entertainment.” Ropes began to show up in kabuki theater.

In theory, only hemp, “inseparable from Japanese culture and religion,” was supposed to be used for the rope. At Shinto shrines, braided shimenawa (rope used for purification) and hemp serve as a “boundary between the everyday world and the spirit realm.”

The tradition extends to sumo wrestling (also considered a Shinto ritual) where the Association of Shinto Shrines does “grassroot work for conservative causes and drums up votes for conservative politicians.”

It’s Hayama’s daunting task to understand the sacredness of hemp rope and the possible connections to his investigation.

Part of his discovery is to learn why Yoshikawa (aka Yoshikama) created a new life, changing his identity as a “departure from reality” like “a character in some kind of story.” When Hayama begins to visit his neighborhood shrine he traces links to politics in a “new constitution, for and by the people.”

A series of Yoshikawa’s confessions outline his immersive seduction into the sex industry learning to turn pain into pleasure when “torment, turns to love, the evil turns to good . . . where everything flips over” as if in meditation. He also becomes involved with a mysterious missing-fingered character and traces “myriad episodes of globalization” where “one culture was baptized as another, bushwhacking through the dusky brush of history” resulting in contemporary Japan with ancestral traditions “either from the mainland or the islands to the south.”

Ultimately, Nakamura resolves the existential dilemma of “human bondage” through a metaphysical understanding of “what life [is] all about.” Hayama’s chief declares “case closed” by making a “story sound okay.” This makes for an intriguing, ambiguous conclusion. To say more would expose major spoilers familiar to most noir fans.

In the evocatively enriching The Rope Artist, respective lives get “tangled up in one big knot” with violence at its core. Identities are altered, licentious secrets revealed in Nakamura’s unflinching, emotionally charged rewarding read.

Robert Allen Papinchak is a former university English professor whose reviews, criticism, and interviews have appeared regularly in The New Yorker, Publishers Weekly, On the Seawall, World Literature Today, The National Book Review, and Mystery Scene Magazine and in newspapers, literary journals, and online. He was named a Finalist for the 2022 Kukula Award for Excellence in Nonfiction Book Reviewing by The Washington Monthly. His fiction has been nominated for the Pushcart Prize and won a STORY award. He is the author of Sherwood Anderson: A Study of the Short Fiction.