Q&A: Cris Mazza Talks Family, History, the Slipperiness of Memory, and the Hybrid Essay

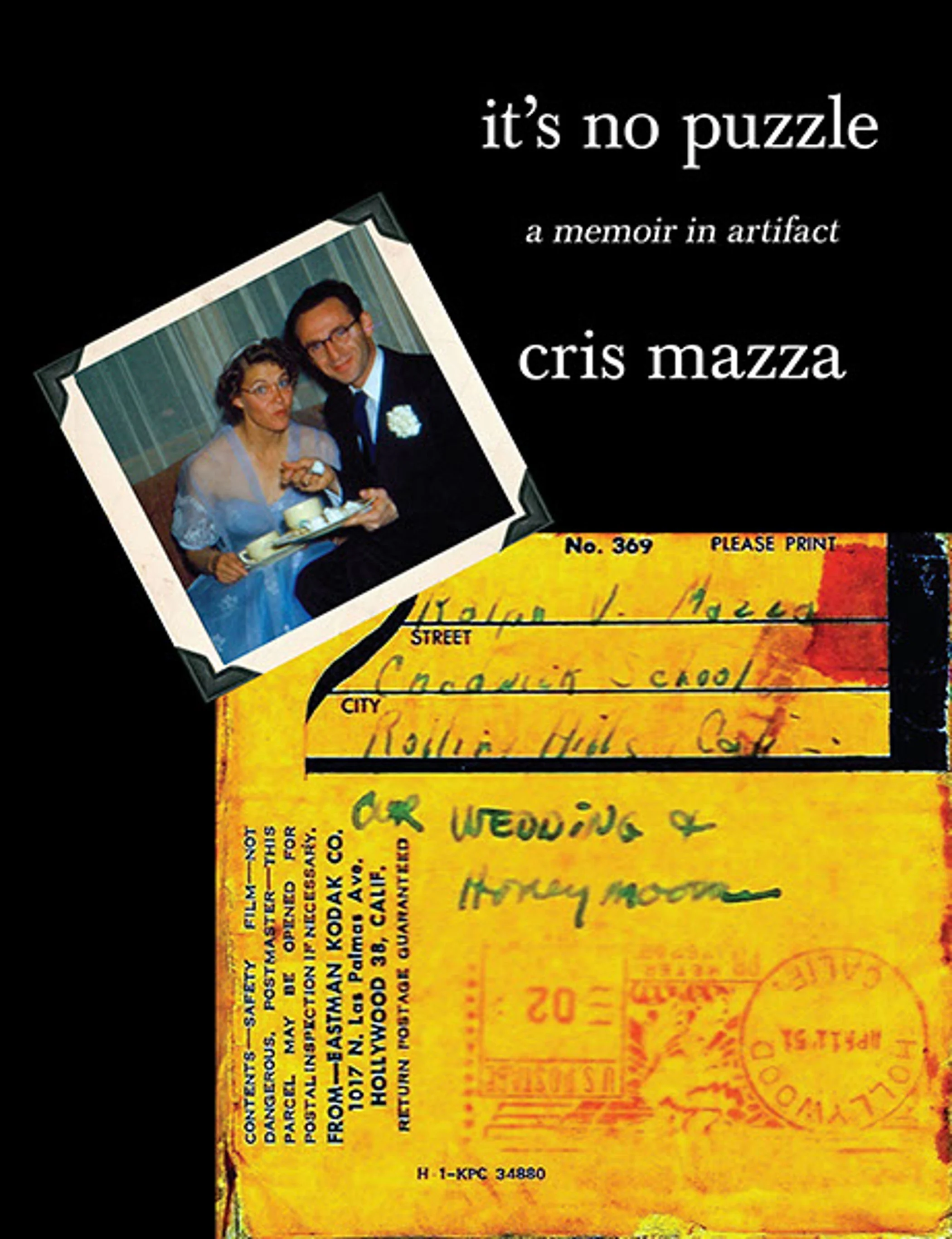

/In It’s No Puzzle: A Memoir in Artifact (spuytenduyvil), Cris Mazza combines photographs, newspaper articles, and other visual ephemera with the personal essay to work through questions of familial and cultural inheritance. Triggered by the death of her parents and by the difficulties of the Trump years, Mazza spent several years sorting through her mother’s copious photographs and slides, as well as through her own archives from four decades of teaching and writing. The completed project is dizzying in scope and depth. Mazza brings an astounding level of rigor to her investigations, even when her detective work leads her to some inconvenient conclusions. She uncovers inconsistencies and missing facts in family lore, and discovers new facets of her parents’ early years—as well as unanswerable questions.

A native of Southern California and a long-time professor in the Program for Writers at the University of Illinois at Chicago, Cris Mazza has authored twenty books, including novels, short story collections, and creative nonfiction. It’s No Puzzle advances her previous work in hybrid memoir and is an unflinching look at personal and communal loss, recovery, and re-examination.

For The National Book Review, Rachel Swearingen spoke with Mazza about her approaches to archiving, to the hybrid essay form, and to writing about family.

Q: In It’s No Puzzle, you detail the monumental task of sorting through family photos, slides, and memorabilia. As I was reading, it struck me that later generations will most likely not inherit the same degree of physical artifacts. What are your thoughts on this?

A: I’m not sure Americans have stopped accumulating “stuff,” judging from the proliferation of rental storage units. But for sure the kinds of artifacts may now be different. No more paper trails. But people still take thousands of (and probably hundreds too many) photos, and it stirs a little anxiousness in me to imagine all those images not sorted and stored where a family might access them and [re]view family experiences. In fact, some high percentage will disappear completely with the discarding of a phone. I still uber-organize all my digital photos, probably more for the sake of not allowing my sense of my own past life to fall into chaos.

Q: You mention hiring a research assistant to help you organize four decades of your own documents from your writing life. Did the process of going through your parents’ effects change how you are handling your own archives?

A: Wow, I actually hadn’t thought about this. With my own archives, I either didn’t have the desire or didn’t allow myself to go down any rabbit holes. My mother’s photos and artifacts, combined with our (siblings’) memories of stories she told, raised intriguing questions that I was able to plunge into, even if I never found “true” answers, like who was the married man who was “bothering” her enough to cause her to quit her first teaching job? Who did she have a crush on? What were her relationships with African American peers in college? The questions that could have caused me to “research” my own career pitfalls and missteps—like why did the New York editor, who later became an agent, ask my agent if I was dangerous?—would have been rabbit holes of humiliation, regret, and even self-loathing of a sort I wouldn’t find the upside of exploring. And yet, perhaps, those are the very questions I should pursue. Unfortunately, the archives to “follow” to those discoveries are non-existent, and, in this case, I don’t see the value in guessing.

Q: In your opening essay, “Complex List,” you dramatize the strange experience of spending the Trump years archiving your parents effects. Do you think you would have interrogated your parents’ lives in the same way without the pressure of this added political turmoil?

A: Maybe. Probably. I don’t know! At the same time I was escaping fully experiencing mounting personal losses, including a beloved dog who went too soon, as well as loss of my visibility as a writer.

Q: Your essay on your father’s time in post-war Germany as a Depot Commander fascinated me, in part because I can sense you trying to place yourself within this larger history that began before your birth. This desire haunts many of the essays, but in this case, it’s magnified by the photos of artifacts brought home from Occupied Germany. How did you choose which objects to include?

A: This is the only essay in the book where I was able to actually ask questions of a living parent. So that’s where I started. Finding out the (dissimilar) range of duties under his supervision—from the train depot’s activity gathering tools of war as well as raw materials, to his command of a unit of German POWs, to sending recordings of the Nuremberg trails back across the Atlantic—I researched those things to try to find the parallels (and irony) between the few details he remembered and any written history of the occupation. I searched his photos and documents for traces of either what he remembered or what I was learning from my research. Then I could show him certain photos and ask what was it them (to be sure I was assuming correctly) which sometimes elicited another memory which gave me another avenue of research. As I developed what the essay would become, I posed the “problem” for myself of making the summary of the area of research column on each page not be longer than the summary (plus artifacts) of his memory in a parallel column. It was truly a puzzle built from not knowing what the picture was going to be when I finished.

Q: You write that the act of photographing and curating photographs “may also affect our reminiscences of childhood—the collective one and the differing individual memories.” Did writing and arranging this book change your sense of your past and history?

A: In a very real way, yes, when I interviewed two young men I’d known in high school and discovered that even in the mid 70s there were organizations that restricted African Americans from entry. Many native Californians (who are as old or older than I am) probably continue to assume that “it didn’t happen in California; that was the South.” I was one of those. Writing this book lifted that veil from my eyes. In other cases, some of my research and contemplation reinforced doubts and confusion that I’d always had, like when I saw the “another girl,” (emphasis mine, but I felt it nonetheless) on my Dad’s telegram to my grandmother after my birth. In all, it probably helped me re-realize that our pasts are subjective stories and we view the events with lenses of influence from other sources, whether or not we’re aware that there are “other sources.” But our reactions to our pasts are real reactions, even if the remembered experience is unreliable.

Q: Your essay about sorting through your mother’s photos and slides raises some interesting questions about collective and individual memory, and about living in the digital age of camera phones. In many ways, you seem to be underscoring the importance of the act of selection itself. Could you tell us a bit more about this?

A: When simpler-to-use cameras became widely owned by the middle class, many people were still careful about how much film they used. Film wasn’t free, and development and printing raised the cost of photography. So it was common to gather people together for one group shot at a picnic or national monument, instead of taking a dozen candid shots. So photos didn’t show as much varied personality in subjects. But, then, more people took care of their photographs: put them into albums, wrote on the backs who was in the shot, etc. I feel tremendous sadness when I see, at estate sales or swap meets, boxes upon boxes of old photos (20s through 60s or 70s) that once were someone’s family record and now are kitsch, at best. Even that much won’t happen with the giga-loads of digital photos. (I think I went into a tangent about something else and not the question you asked.)

Q: One of the things I admire about It’s No Puzzle is that you include potentially embarrassing or shameful cultural artifacts, and you also recognize gaps in your records. How difficult was this for you? Has your view of memoir, and what the genre should do, changed since writing this book?

A: In the back of my head is always the desire to expand what memoir is and what it can do. Plus any dealing with memory (from writing narrative to interviews to court testimony, etc.) is dealing with unreliability and a narrator’s (or speaker’s) own unintentional or intentional filtering of what they’ll include, what they won’t include, the spin they’ll put on it, and the agenda behind any story-telling at all. OK, let me step down from that podium and answer your question: If I’d really expected to find true answers to any of my questions about my parents’ lives, I would have failed and the book wouldn’t exist. I am so grateful that we found the 1950 blackface photo because it was the impetus for at least four of the essays.

Q: Speaking of unreliability, in “Getting Their Stories Straight,” your essay about the private school your father attended, and the school where your parents later taught, you mention that “your narrative also suffers from the unreliability of authorial selection.” Could you explain more about what you meant by this?

A: Related to the answer above: I basically cherry-picked throughout the school founder’s memoir to find portions that suited both my parents’ memories and my (shocking to me) discoveries about the racist intent behind the development of the area where the school was located. My parents viewed the school as a good way to give the children of very wealthy/famous people the benefit of some family-style structure. But when I found the founder’s assessment of the public school she first sent her own children to in San Pedro—a Navy and commercial fishing town in the Port of Los Angeles—it could be read as racist and classist. Choosing that quote might tend to slant the founder’s whole view of the school she built toward racism, which it was not. But that’s what authorial choices do, and it’s the role they play in writing this type of nonfiction. I let my choice of evidence speak for itself, but I wanted to admit up front that what I included and what I didn’t smacks of unreliability—as all nonfiction does.

Q: Do you think it’s important to try to separate our individual identities from cultural history?

A: But can we make that separation? Could or would any of us be who we are without the cultural histories we’ve lived through? Even though I didn’t refer to The Depression at all, I can’t imagine who my parents would have been without The Depression and WWII, not to mention The Cold War. Will or has the covid pandemic impacted the individual characters and identities of Gen Z or the generation that comes after?

Q: There’s a culminating sense of urgency in your examination of your parents’ and your own history in these essays. Do you feel that same urgency now? Or did this project bring a sense of resolution?

A: After one of my sisters read the book, she told me another story she’d heard from our Mom regarding another man flirting with her during the first few years of her marriage when my two older sisters were toddlers. Having the book already in print, it was a lost opportunity for another research-journey. I regretted not hearing of this sooner, but I also wondered if I could conjure the same intensity of immersion as I’d had while originally working on this book. And yet an aspect of my parents’ marriage was not included in the developing of their young adult “selves.” I think there will never be real resolution about “knowing” my parents, because there were five of us: that’s five people with five different memories and perceptions of five different yet overlapping segments of our parents’ mid-adulthoods. Just considering that gives me an unsteady and shifting lack of stability in any claim to “know” my parents.

Q: By displaying family artifacts next to the newspaper clippings and scraps of research, you raise questions about how slippery stories are when facts, especially unflattering ones, are left out. I would love to hear your thoughts on the powers of hybrid nonfiction. Has this project changed the way you think about memoir?

A: First, I wanted the artifacts and images to stand for themselves as much as possible, without commentary or captions. (The exception was “Ask the Depot Commander,” where certain photos from 1945 Nuremberg needed information—or guesses—about what was being shown.) Many of the news articles and old advertisements, of course, did not need me to chime in about their obvious racism. So in a way it was how I was able to characterize that era (and that industry: real estate) without a skimmed-over summary, but with actual validation. Any personal nonfiction that would want “actual validation” for something claimed about the setting, culture, era is, in my view, hybrid or leaning that way, since so much memoir is pure authorial memory and feeling offered as true and factual. So it’s possible my view of memoir has grown more extreme than it had been, either asking for research and evidence to sit side-by-side with personal experience, or admit the untrustworthy slant being offered, and don’t strive for the “recovery” resolution … something you find instead may be much more interesting and even more universal.

Q: You’ve written twenty books—novels, short story collections, memoirs. What are you working on now?

A: I have a new completed manuscript that is structurally similar to It’s No Puzzle. It’s called The Decade of Letting Things Go, and it is more focused on my own experiences with coupling, longing, divorce, relationships with the world around me, sexual dysfunction, #MeToo, losing parents, seeing an esteemed mentor crumble, coming to terms with childhood scars … all in a decade post-menopause when I’m supposed to be invisible.

Rachel Swearingen is the author of the story collection How to Walk on Water and Other Stories. Her stories, essays, interviews and reviews have appeared in Electric Lit, VICE, The Missouri Review, Kenyon Review, Off Assignment, Agni, American Short Fiction, a