REVIEW: Lorrie Moore's New Novel Centers on a Suspended Teacher in Meltdown

/I Am Homeless If This Is Not My Home by Lorrie Moore

Knopf, 208 pp.

By Robert Allen Papinchak

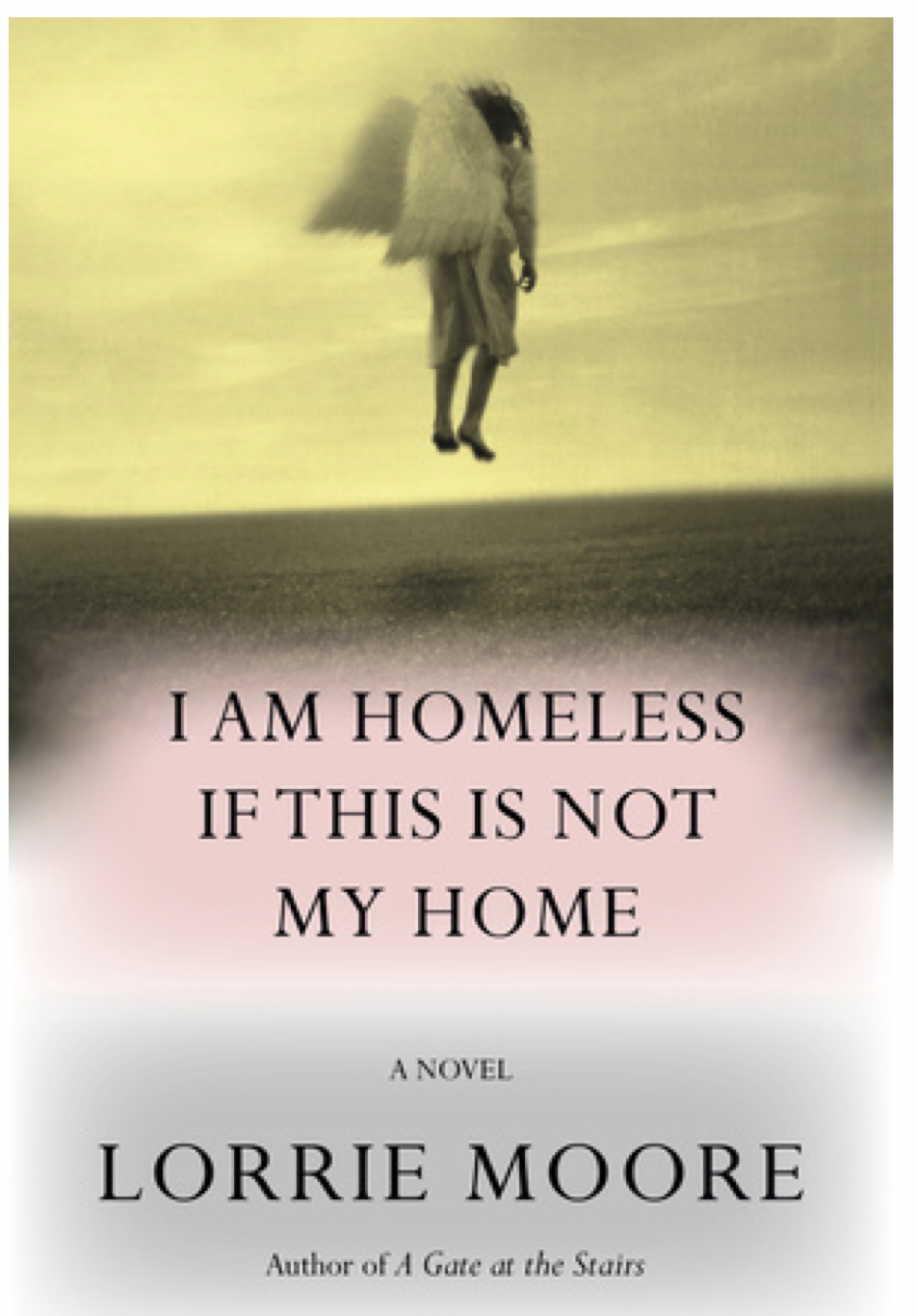

Don’t judge a book by its cover? Why not?

The first clue that something may be amiss in Lorrie Moore’s bold, evocative I Am Homeless If This Is Not My Home is the winged, ascending angel floating in a blindingly bright yellow sky above a faraway horizon. Provocative questions arise: Who is it? Where is it going to? Or coming from?

Beyond the alluring cover is a poignantly dark manifestation of a macabre road trip that explores haunting memories of sibling connections and a childhood past, lost love, gut-wrenching guilt, lingering grief and the valiant effort to assuage it all.

At the center of the bizarre narrative is beleaguered Finn. He has just been suspended from a teaching position in Illinois for “wandering away from the curriculum,” focusing on math instead of history and taking a “stand against homework.” With his landlady’s disposable cat box sliding around in the back seat of his Subaru (don’t ask) along with “glass shards in a paper bag from a broken goblet” rattling around (don’t ask), he has driven straight from the Midwest to an Airbnb in the “industrialized zone of Chelsea” in an unrecognizable New York.

It is now “No York: all these neighborhoods telling him ‘No.’ ‘NoHo—a guffawing denial, ‘No Mad’ where he was staying . . . ‘Nolita.’ Didn’t he date her in high school? Or rather junior high? “

He’s there--kept awake until two am by all night jackhammers--because his older brother, Max, is dying from cancer in a hospice in the Bronx. Suffering from his own terms of endearment he wrangles with young Ghanian aides and nurses to “’get a little juice or something.’” At the same time, he’s attempting to cheer up Max with “props,” a photo of them holding baseball bats in their youth, or watching the Cubs and the Indians in the World Series.

Max’s memories are waning. He’s not sure where he is. Finn becomes complicit with Max’s wife, Maxine, who has asked him to lie and just say his brother is in a hospital. They chat about Finn’s suicide pron ex-wife, Lily, who is contending with her own demons back in Illinois.

Before Finn, as Max’s “death doula,” can “grow their brotherhood like a beautiful garden at long last,” he gets a call from one of Lily’s book group companions telling him he must return to “urgent matters.” He abandons Max with an “illogical sense of hope” that he will outlive hospice odds and rushes back for the seventeen hour drive through the Holland Tunnel, through the keystone, buckeye, and hoosier states, only to discover that Lily has succeeded in taking her life in a rather unusual, outlandish drowning incident in a shower.

That’s when the novel enters the grotesque zone. Ironically, Lily had practiced “laugh therapy,” dressing as a clown to “try to shake people, mostly children, out of their gloom.” She “understood enfeebling malaise” but could not shake her own despair. She had a red nose, “even wore floppy shoes, the laces of which she had once used to strangle herself.” She was buried in a “green cemetery” in those clown shoes (“men’s oxfords with floppy glued on extensions”) with only a grapefruit marking her otherwise unmarked burial site.

Finn knows Lily had other final wishes so he seeks out the cemetery and the grapefruit. What he discovers is Lily an undead dead, “standing in dead fleabane,” wearing her “shroud around her, a cocooning filthy gown . . . like an infinity scarf gone very wrong.” He vows to take her to a “body farm in Knoxville, Tennessee.”

That outlandish road trip takes up the remainder of the surreal, head spinning misadventure. Finn helps the decomposing corpse into the passenger seat of the car trying not to think that “what he was doing could be misconstrued as body-snatching.”

Despite their disheveled and “sketchy” demeanor they manage to get a room at the South Sunken Road inn where the owner is “no stranger to swamp people.” Their gothic room suits them—“dank as a church [smelling] of old wallpaper paste.” Bathroom and bedroom windows “were patched with ambrotypes serving as make-do stained glass.” The place is from another era.

It’s there that Finn discovers a “brittle and faded red [book] with a cracked spine and tawny, deckled pages . . . a woman’s journal all handwritten in the form of letters.” Unsent letters from one sister to another in the nineteenth century that reveal a secret life at the same decrepit inn where Finn and Lily are staying.

Finn steals the journal. It becomes numerous entries in the novel that prove to be a kind of posthumous confession. They are a palimpsest of memories that sometimes echo events in Finn’s and Lily’s life (the writer has a pernicious thespian “gentleman lodger” with a cork foot named Jack; Lily’s belligerent husband was named Jack). The writer reveals a mind-twisting secret. Memories from “another time and other people and in the form of humidity saturated the place. Any given time always had other times underneath it.”

There are graphic descriptions of Finn and undead Lily having sex in the car with her “shifting organs” and “silverfish in her perfumed hair.” Of Finn bathing Lily at the inn: he “slipped her into the tub with all her clothes and wrappings . . . her body was both strange and familiar, her breasts parabolas of blue and brown, and when the evening light shifted outside her ashy skin seemed to have phospherence in it. Her torso was mottled but also creamy like a New Age candle, and he pressed his lips to the closest part of her branching collarbone.”

After Lily reaches the “dead end” of her final resting place, Finn still needs to contend with Max’s demise. And to understanding what he learned from the double journeys. His “old life seemed a swirl of smoke in a jar. He saw that no longer caring about a thing was key to both living and dying. So was caring about a thing.” Love lingers through others. ‘‘Nothing in this world was ever truly over.”

The past ascends. Perhaps that’s Finn on the cover. Perhaps it’s Lily. Perhaps it’s Max. Everything that rises might converge in the slim, fulfilling I Am Homeless If This Is Not My Home.

Robert Allen Papinchak is a former university English professor whose reviews, criticism, and interviews have appeared regularly in The New Yorker, Publishers Weekly, Los Angeles Review of Books, On the Seawall, World Literature Today, The National Book Review, Mystery Scene Magazine and in newspapers, literary journals, and online. He was named a Finalist for the 2022 Kukula Award for Excellence in Nonfiction Book Reviewing by The Washington Monthly. His fiction has been nominated for the Pushcart Prize and won a STORY award. He is the author of Sherwood Anderson: A Study of the Short Fiction.