Q&A: Mary Gabriel Talks About Madonna's Rebellion and Legacy

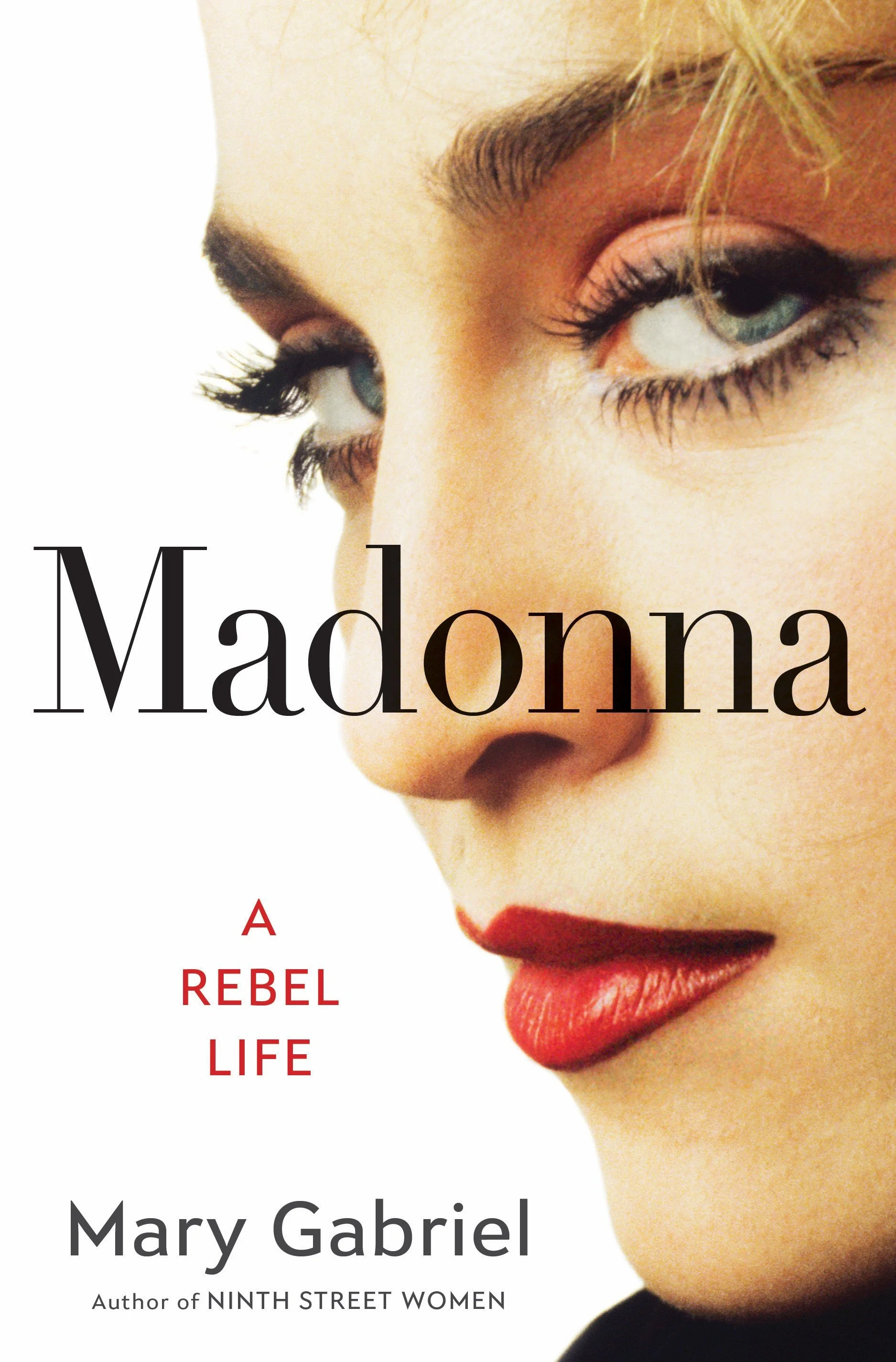

/In her vivid and comprehensive new biography, Madonna: A Rebel Life (Little, Brown), Mary Gabriel traces the iconic star’s childhood roots in Michigan to her global stardom. Gabriel has a talent for powerfully evoking boundary-pushing women artists as she displayed in her award-winning Ninth Street Women: Lee Krasner, Elaine de Kooning, Grace Hartigan, Joan Mitchell, and Helen Frankenthaler: Five Painters and the Movement that Changed Modern Art (Little Brown, 2018). John B. Valeri discussed Madonna’s life and legacy with Mary Gabriel for The National Book Review.

Q: Madonna is one of the most written about people on the planet. What drew you to her story? As she embarks on her “Celebration” word tour, why is she as relevant today as when she first emerged forty years ago?

A: To answer the second part of your question first, I believe that she is as relevant today as she was then because we’re still hungry for art and the social issues that she has spent a lifetime addressing are still critical. Amazingly, the pendulum is swinging back radically toward repression and discrimination; repression of women and discrimination against the LGBTQ community and racial, religious, and ethnic minorities. That was the world she lived in when she began her career, that was what she was rebelling against as she used her music, videos, films and life to point a way toward freedom and, I’m tempted to say tolerance, but it’s more than that – toward love. The world needs Madonna as much as it did in the early ‘80s.

Now, to your first question. What drew me to her? I wanted to continue writing about women artists but I feared that if I wrote another book about a woman painter or sculptor, I would repeat myself. Plus, I wanted to move closer into our time chronologically. My last books have been in the 19th and mid-20th centuries and I wanted to experience writing about today. I decided on Madonna after hearing her 2016 Billboard Woman of the Year speech. It was so honest, and such an important message delivered at a very raw moment after the 2016 election, that it stopped me in my tracks. It also made me – and I’m sure I’m not alone in this – view Madonna in a completely different light. I realized how misunderstood she is, despite as you say being written about more than just about anyone on the planet. And I realized that I could help reintroduce her by telling her story in a new way.

Credit: Mike Habermann

Q: You tell Madonna’s story within its cultural, historical, and even geographical context. Why is this important to our understanding of her development – and how did you endeavor to meld this background into the biography so that it enhances your narrative rather than overwhelming it?

A: This is something I have done in all my books. I think we are all the result of where we live, who we know, and the historical period in which we live. In other words, we are inseparable from the forces around us and so to describe an individual’s life and development, you need to describe those people and things that impact them at any given moment. I try not to let those external forces become the story by making sure I remain focused on the individual – on Madonna. She might disappear from the narrative for a page, even two, but I try as quickly as possible to bring it back to her. I often say it’s a way of telling a story horizontally, rather than vertically. It’s not a timeline of a life that travels from point A to B, but a sweeping landscape that moves in sync. Anyway, that’s a grandiose and probably overcomplicated way of saying I try to put my characters in context.

Q: The book opens with Madonna’s 2000 mini-concert at London’s Brixton Academy before proceeding in a chronological telling. Why did you choose this moment in time as an entry point? In what ways does it represent an ideal vantage point from which to look ahead and behind?

A: It was very difficult to imagine how I would end this book because Madonna is alive. I needed to stop writing at some point, but she would still be working. In the interest of a narrative arc, I decided to open the book at a small concert in London because I planned to end it at a smallish concert in London. The Brixton show was also important because it represented a real turning point for Madonna. Prior to that, she was based in the United States and worked mostly – aside from William Orbit – with American collaborators. Beginning in 2000, Madonna rebased her world and her work to Europe. It felt to me that the “adult” Madonna was born that year, with her second child and her second marriage, and that that was a good place to introduce her story, before dropping back to explain how she got there.

Q: You preserve Madonna’s voice throughout the book despite not having interviewed her. Tell us about your approach to capturing her perspective. How did you go about augmenting this with other, sometimes contradictory, viewpoints to present an intimate yet objective portrait?

A: It’s frustrating to write about a living person and not be able to speak with them. In fact, one of the things that drew me to this subject – or at least to a modern subject – is the possibility of interviewing them. Everyone else I have ever written about has been long dead. When it became clear that I wouldn’t be able to speak with her, I decided to write the book the way I had my other historical biographies, by finding everything that person has ever said and written, and by finding interviews, books, articles – anything and everything that those who knew her and worked with her wrote and said. Luckily for me, the public conversation among all those characters has been ongoing for forty years. There was no lack of material.

It was really important for me to have those voices because nothing annoys me more in reading a biography than paraphrasing. I want to hear how the person speaks and what the person says – in their words – and not an expert’s version of it. I want to hear how her friends and colleagues speak about her, as candidly as possible, in their own words. And crucially, I wanted to hear what the various characters said at the time. I love to be able to quote Madonna in 1983 in the words and voice she had then, rather than have a mature Madonna recall that time. Using quotes from various interviews through the years, gives readers a chance to hear Madonna’s evolution as an artist and a person, to see how she changed and how she was forced to change. The same is true of her associates. How did they speak of this phenomenon called Madonna in the early ‘80s compared with how they spoke about her in 2020? How did the press speak about her over those years? It’s fascinating to watch and listen.

Q: Madonna’s talents as a lyricist and musician are often overlooked. You remedy this by spotlighting the development of her songs/albums. What was your process like to understand and convey the inner-workings of her creative process – and how does it challenge common perceptions of her as a “singer”?

A: That’s such an important point. I think oftentimes people think of pop stars as manufactured products – like breakfast cereal, they’re concocted by a room full of entertainment industry executives and hot producers. And that is what happened in later years to other artists, unfortunately. But Madonna is not a pop star. She is an artist, in fact she’s not a singer at all, she’s a performance artist. Music is just one aspect of what she does. I think a lot of people don’t realize that she wrote her own songs, and even when her name is listed as writer or co-producer, they doubt whether she really had a hand in the song’s creation. I can tell you that there is not a single producer or musician who has ever worked with Madonna – at least not one who I discovered – who ever said she was anything less than a full partner in an album, and in most cases, she was the ultimate force directing the project. Every album was a “Madonna” album, no matter how many producers she had working on it, because she made sure that it was. In 1995, she overtook Carole King as the woman songwriter with the most number one hits, and that was a position that King held for 30 years.

I tried to tell the story of her work as a songwriter by taking the reader into the studio with Madonna and her producers for each of her albums. I let them describe the process and Madonna’s role in it. And, again, it’s fascinating to see how that environment changed as people playing musical instruments were replaced by computers, and as the number of people it took to make a record swelled from a handful to a small army.

Q: Given her dynamism, Madonna is perhaps best viewed as an “artist” rather than a more singular entity (singer, actress, author, businessperson, dancer, etc.). What did you discover about her unique approach to the creation and presentation of her craft(s) – and why is this an important distinction in considering its merits?

A: You’re absolutely right. Madonna is an artist, or I would say that she’s a performance artist. Her approach to her work is partly due to her insatiable curiosity across art forms, but also to the environment in which she became an artist. Madonna, as we know her, arose out of downtown New York in the late ‘70s and early 1980s when distinctions did not exist between art forms. A person could be a painter, singer, film director, author, actor, dancer, songwriter, producer without anyone questioning why they didn’t settle into a particular category or tsk tsking that they were spreading themselves too thin. The environment was about discovery and cross-pollination. It was also a world in which high and low art did not exist. Just because someone didn’t show in an established gallery didn’t mean they couldn’t call themselves a painter. And just because someone’s work was popular, didn’t mean they weren’t serious or a “real artist.” You could trace that particular attitude back to Andy Warhol, the father of Pop with a capital P culture. Madonna and her crowd knew him and adored him and, most importantly, were inspired by him.

Madonna took those ideas and made them mainstream. She was, as far as I know, the first “pop artist” – as in popular – to dare to be everything. And she made that possible for those who followed her. They were no longer bound by the constraints of genre.

Q: One of the things I found most revelatory in your telling of Madonna’s story is her role as mentor to a younger generation of (on-stage and behind-the-scenes) talent. Tell us about this aspect of her character and how you think it relates to her own journey from aspiring performer to global superstar, and the obstacles she’s faced along the way.

A: That is one of the least understood aspects of Madonna’s career. She’s often accused of trying to be like younger artists, or appropriating the style or art of underground movements and people. In fact, the opposite is true. She has made a career of inviting young artists who didn’t dare dream of being on a stage as large as hers into her work, and they didn’t rest in a corner. She made a point of acknowledging them and celebrating them. The same is true of underground art forms. Madonna doesn’t appropriate. If she finds something interesting, she gives it a global stage and she makes sure those people who created it are given credit. The best example is the Ball culture in New York. Madonna was sharply criticized for so-called appropriating it in her “Vogue” video. In fact, she loved it and wanted to share it with the world, and to do that she asked some voguers she discovered in New York to help her. It wasn’t theft, it was tribute.

As far as the musicians and producers she worked with, she has always said that she preferred working with people who were considered unknown. She didn’t want sounds that were already familiar, she wanted to work with people who were at that wonderful moment of discovery when new styles are created and new avenues opened. I would argue that her only weak album (and I use the word weak reluctantly) is one she did with producers who were so mainstream that they dominated the music industry.

Finally, there is a false narrative that has followed Madonna since the ‘90s, and it is that she is competing with younger women performers. That is a media-generated fantasy created in a world where women aren’t allowed to support one another. It’s sadly and stupidly rooted in the notion that women compete with each other for the attention of men. Throughout Madonna’s career, time and again, she has offered support to younger women artists, especially when she saw them being abused by the press and the entertainment industry. Far from competing with them, she has championed them.

Q: If you had to create a playlist of your essential Madonna songs, which would you choose?

A: That’s the hardest question of all! I’ll throw out a couple but not in any particular order: Live to Tell, Like a Prayer, Deeper and Deeper, Where Life Begins, Take A Bow, Inside of Me, Hung Up, Get Together, Die Another Day, X-Static Process, God Control, Crave, Crazy, Dark Ballet.

And that’s just the beginning!

John B. Valeri is a book critic, author, and host of the web series “Central Booking” who has written for CrimeReads, Criminal Element, Mystery Scene Magazine, The Big Thrill, The National Book Review, The New York Journal of Books, The Strand Magazine, and Suspense Magazine. His popular Examiner.com column, “Hartford Books Examiner,” ran from 2009 – 2016 and was praised by James Patterson as “a haven for finding great new books.” Visit him online and watch past episodes of “Central Booking” at JohnBValeri.com.