REVIEW: David Grann's Epic Story of Shipwreck and Mutiny During the Quest for Empire

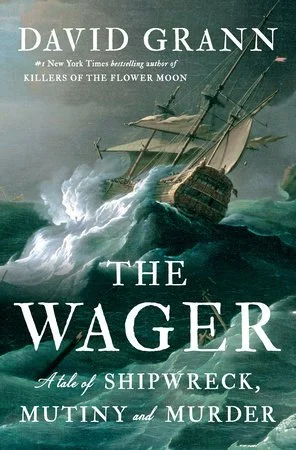

/The Wager: A Tale of Shipwreck, Mutiny and Murder

By David Grann

Doubleday, 352 pp.

By Ann Fabian

A couple of years ago, one of my children gave me a copy of a collection of David Grann’s stories The Devil and Sherlock Holmes: Tales of Murder, Madness, and Obsession. Most of those stories had appeared in The New Yorker, but the title of the collection nicely captures the something of Grann as a writer. He is a reporter with the patience of a detective and the persistence of a historian and a man with the stomach to spend months in the company of murderers, madmen and obsessives.

Like a lot of you, I’d been gripped by Grann’s Killers of the Flower Moon: The Osage Murders and the Birth of the FBI, his account of the “reign of terror” that greedy, violent white Oklahomans brought down on the newly oil-rich Osage people in the 1920s. The sprawling evil and raw suffering running through the story are hard to fathom. But it’s also hard not to admire the humanity Grann brings to his retelling and to marvel at the archive he assembled in the process: trial records, prison files, dime novels, detective reports, yellowing newspapers, family memories and more.

In his new book, The Wager: A Tale of Shipwreck, Mutiny and Murder Grann picks up a tale set in the 1740s, a decade when Spain and England—vying to subject native peoples, control the world’s mineral riches and bank the wealth produced by enslaved laborers—sent shiploads of men to square off on the high seas. Those imperial encounters boiled over when a Spanish officer boarded a British brig, accused the captain of smuggling sugar and cut off his ear, launching the conflict known as the War of Jenkins’ Ear—a bit of pub trivia that also left us, Grann writes, “one of the longest castaway voyages ever recorded.”

The Wager was a royal navy vessel manned with 250 officers and crew and carrying munitions for a squadron of six warships. It set sail from Portsmouth in September 1740. Bad weather and bad decisions chased the ships around Cape Horn, and the Wager wrecked on an island off the coast of Chile in May 1741. Everyone assumed the men and their boat were lost. But almost nine months later, a remnant of the crew staggered ashore in Brazil. Several months after that, more of the crew appeared in Chile. Those survivors had stories to tell—and to sell.

The voyage was snakebit from the start. For all England’s imperial swagger, naval crews of the 1740s were a sorry lot—wretched men impressed into service, invalids pulled from pensioners’ homes, second sons without better prospects and dozens and dozens of young boys—all commanded by officers whose power often harbored a streak of cruelty. The situation was made worse on the Wager when lice spread typhoid through the squadron before the ships had left port. At sea, scurvy decimated the crew. “Dead reckoning” proved a poor tool for sailors caught the currents of the South Atlantic. Rats and worms ate the ship’s stores. Hurricane winds ripped sails. Navigators lost the way. Men lost their minds, their limbs and their lives. “So miserable was the scene,” one wrote, “that words cannot express the misery that some of the men died in.”

By the time the Wager ran aground off Chile in May, the ship had lost nearly half its crew. The remaining 145 castaways were a haggard, sickly, quarrelsome bunch, although some were resourceful enough to bring onto the island pieces of their sinking ship along with what they could salvage of food and rum. Thanks to the Kawésqar, sea going peoples of the Patagonia coast, the Englishmen added shell fish and seaweed to the meager rations saved from the ship’s stores. But the shipwrecked sailors, clinging to delusions of their racial superiority, drove the Kawésqar away. They fought, drank, stole, drowned, got sick and died. The castaways were lucky that an ingenious carpenter had survived the wreck. This man fashioned a long boat into a craft to carry men back around the Cape into the Atlantic and north to Brazil,

It is a wonder any of the Englishmen survived and I confess I lost count as the number of living dropped. (Maybe a dozen men of the original 250 made it back?) With his characteristic ability to follow his stories right through what seems their darkest moments, Grann brings out the horrors on the island and the terror of men crowded onto rickety crafts. How can it get any worse, I kept wondering. But I’ve read enough of Grann by now to know that it always does get worse: the evil in Oklahoma, the stupidity of some sailors.

What really happened during those shipwrecked months? Mutiny? Murder? Starvation? Cannibalism? Scenes from “a Hobbesian state of depravity,” Grann imagines? Or a community of men opting to follow natural leaders rather than incompetent officers?

Survivors included the ambitious captain, David Cheap, and John Byron, a 16-year-old midshipman, a compassionate man, and grandfather of the poet, whose account of the wreck inspired Patrick O’Brian’s novel, The Unknown Shore. Grann’s chief witness, however, is a gunner named John Bulkeley. Bulkeley was “a true seaman,” Grann writes, the father of five children and a devout Christian who’d spent more than a decade in the navy. He shares qualities with many of those who figure in Grann’s stories—a natural leader, determined to survive whatever the odds. While his shipmates continued to die, Bulkeley hunted, foraged, read accounts from earlier shipwrecks and plotted a course to take survivors back around Cape Horn and north to Brazil.

The charisma and competence that drew Grann (and many of the castaways) to Bulkeley antagonized his superiors. Captain Cheap, gripped by vanity and clinging to British naval codes, tried to quell what he saw as brewing insubordination. He had men beaten and flogged and finally shot a drunken midshipman. In his mind, the best way to reach England was through Spanish settlements in Chile. With frayed tempers, the surviving men split into two groups. “Although the dispute centered on a simple matter of which way to go, it raised profound questions about the nature of leadership, loyalty, betrayal, courage, and patriotism.” The dispute also led to competing interpretations of the events on the island. Had Bulkeley led a mutiny? Would he return to England only to be hanged? Had the captain murdered a man? Would he come home only to find his career in ruins?

Grann doesn’t pass judgment on the men of the Wager. But the competing accounts of events give him a chance, as one would expect in a story by Grann, to speculate on the nature of truth and to write about the writers, especially John Bulkeley, whose stories he has pulled into his narrative. Unlike senior officers, Bulkeley wasn’t required “to maintain a logbook, but he kept one for himself anyway,” vowing “to be exceedingly ‘careful in writing each day’s transaction,’ in order to ensure a ‘faithful relation of facts.’”

The gunner knew his “faithful relation” would prove valuable were he to be charged with mutiny but he also recognized a new market for stories like his told in the voices of ordinary people. He and the ingenious carpenter enlisted a friendly London bookseller and published Bulkeley’s journal, remarking in a preface that “[p]ersons with a common share of understanding are capable of committing to paper daily remarks of matters worthy their observation, especially of facts in which they themselves had so large a share. We only relate such things as could not possibly escape our knowledge, and what we actually know to be true.”

The Admiralty declined to try the castaways—worried perhaps that sorting through the competing stories would expose the depravity (mutiny, murder, cannibalism) of the shipwrecked men and cast doubt on the British Empire’s civilizing mission. Freed of suspicion, Bulkeley set off for Pennsylvania where he recruited one of Ben Franklin’s printer apprentices to bring out an American edition of his narrative. With his story told, the gunner slips out of history.

In the end, The Wager is a great weave of many yarns: a naval adventure for fans of Patrick O’Brian, a story of seafaring for armchair navigators, a tale of men in adversity for moral philosophers, an account of printing and publishing for book historians and a great read for all of us tossed around on the waves of our “post-truth” society. There are details on naval surgery, descriptions of sailors’ quarters, a blow-by-blow account of a naval battle and even the capture of the Spanish Galleon.

But through it all, if often just over the horizon, the slave trade haunts Grann’s story. That traffic in human beings surfaces powerfully in Grann’s attention to John Duck, a free Black sailor who once offered to give a bare-headed John Byron his hat. Duck survived the wreck only to be kidnapped and sold into slavery. History has lost John Duck, Grann writes, “as is the case for so many people whose stories can never be told.” “Empires preserve their power with the stories they tell, but just as critical are the stories they don’t—the dark silences they impose, the pages they tear out.”

The dark silences that Grann acknowledges were left in the Wager’s wreck brought me back to Tiya Miles’s All that She Carried: The Journey of Ashley’s Sack, a Black Family Keepsake. Miles works from the sparest of archives: some fifty words stitched onto a sack. Following the lead of others who have called our attention to silences in the archives and taught us to chart slavery’s reach in stories we’ve told, Miles recovers the lives an enslaved woman, a daughter who was sold and their descendants.

I don’t think Grann had Miles in mind as he scanned the torrent of words left from this shipwreck, but her book drives home his haunting point about stories and power. Instead of shelving Grann’s book next to my collection of sea stories—Robinson Crusoe or Mutiny on the Bounty or White Jacket—I’ll put The Wager next to All that She Carried and bet on the writers Grann and Miles inspire to recover the pages empires and enslavers have torn out.