REVIEW: A Humane Memoir by a Victim of the Charlie Hebdo Terrorist Attack

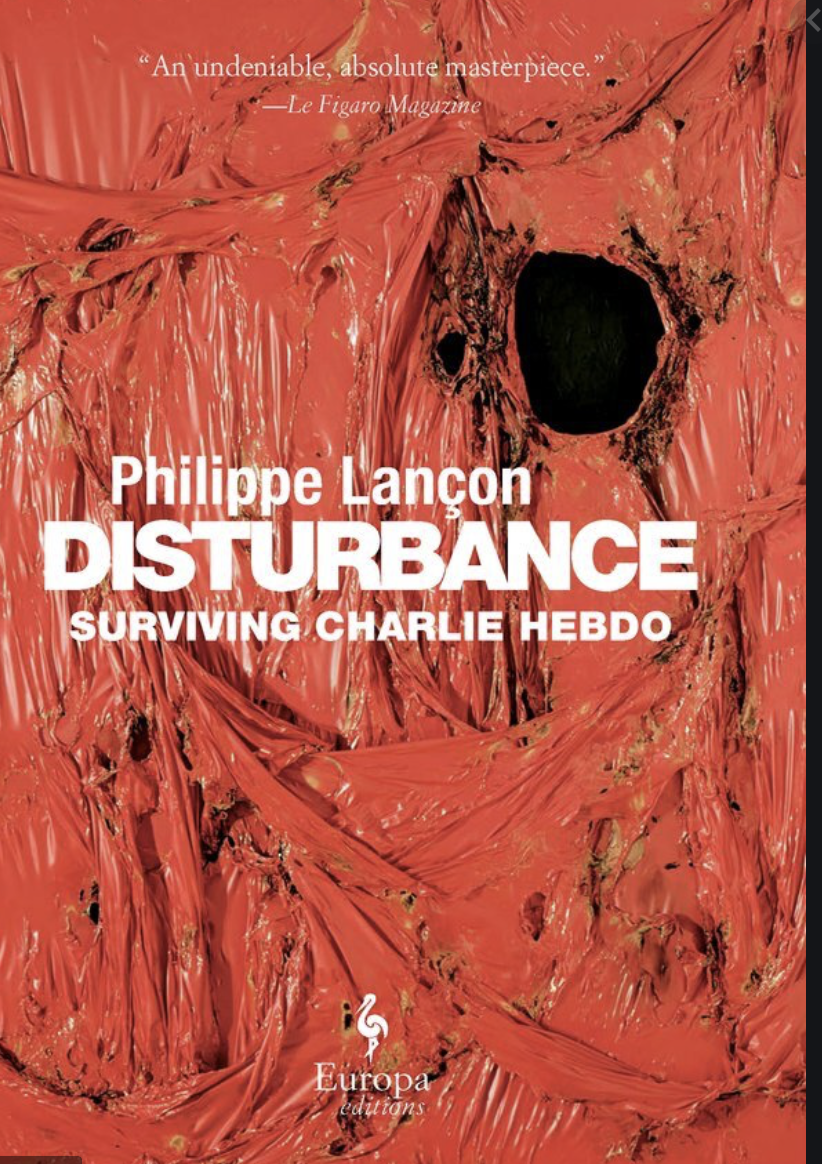

/DISTURBANCE: SURVIVING CHARLIE HEBDO, by Philippe Lançon, translated from the French by Steven Rendall.

Europa Editions, 473 pp.

By Rayyan Al-Shawaf

In Disturbance, a memoir-cum-contemplative essay, author Philippe Lançon displays a knack for elucidating seemingly portentous musings – his own – in an unassuming and accessible manner. When he recalls his “earlier life,” it is not the transmigration of his soul that he has in mind, but his five decades or so in the same skin before a shooting attack that left him hospitalized and in need of facial reconstructive surgery. “[W]here my chin and the right half of my lower lip should have been,” he explains, “there was not exactly a hole, but a crater of torn, hanging flesh that seemed to have been put there by the hand of a childish painter, like a blob of gouache on a picture.”

And when he points to a book on jazz as having “probably saved my life,” he does not mean that it took a bullet for him during the attack, or even that it served as some sort of metaphysical balm without which he would have committed suicide in its aftermath. Rather, had he not paused before his intended departure from his workplace’s conference room in order to show a colleague a photograph in the book, he would have run into the gun-toting assailants in the office building’s stairwell, and almost certainly gotten killed. In that conference room filled with people, he was one among several targets. So he had his jaw blown off.

Lançon is a longtime contributor to Charlie Hebdo, the French satirical weekly magazine with a history of skewering, among other sanctified figures, the Prophet Muhammad; he was in the publication’s Paris offices that fateful day in January 2015 when two Islamists of jihadi bent burst in, automatic rifles ablaze. All told, the two attackers, brothers Said and Cherif Kouachi, killed 12 people. The author was one of the 11 who were injured. His book, Disturbance, is subtitled “Surviving Charlie Hebdo,” and traces the tentative emergence of a new-old Lançon during his nine months in two hospitals following the attack. As doctors and nurses go about constructing a new jaw for him out of the bone in one of his calves, he does his utmost to stay sane – even as “all the worlds in which I had lived, all the persons whom I had loved began to cohabit in me without precedence or decorum.”

Disturbance, translated from the French into fluid and natural-sounding English by Steven Rendall, is a curious work. A seasoned writer (journalist, book critic, and occasional novelist), Lançon pointedly resists the temptation afforded by his harrowing near-death experience to embark on a quest for profundity. Instead, he chooses to wander far and wide in pondering matters personal, literary, and cultural. An award-winner in France, Disturbance has its boring stretches and sometimes comes across as the product of a rarefied mind oblivious to jihadi ideology and practice, but its erudition is matched by emotional discernment and complemented by humor.

In the wake of the attack, the people whom Lançon has loved do not only intrude upon his consciousness and – as he puts its – cohabit there; they converge on his hospital room. For instance, his France-based ex-wife hurries to his side, while his girlfriend, who lives in New York, catches the first flight to Paris. At times, this makes for something approaching screwball comedy. “As in a vaudeville play,” he observes, “the ex-wife had to leave so that the new one could come in, and all the more because the latter was unaware of the former’s presence.” There are poignant scenes, too. For a long time, Lançon’s wounds make it impossible for him to speak to his ex-wife, his girlfriend (and apparent wife-to-be), or anyone else on hand; he uses a marker and a whiteboard to communicate with them. He also keeps a journal of his impressions and reflections, some of which he will later incorporate into this book.

“It was in a space and a time for which nothing could have prepared us” is how the author at one point sums up the Charlie Hebdo attack. Alas, Disturbance does little to illumine that space and time; for all his wide-ranging and in-depth divagations, Lançon gives short shrift to the question of whether the attack heralded a new era or served as a manifestation of one that had already begun. Was the even bloodier Bataclan massacre, which Lançon touches on toward the end of the book, and which was also carried out by jihadis, a sign of this new space and time’s durability? Or was it one of the last gasps of a movement that is on the run everywhere – from Raqqa to Mosul to Paris to Kandahar? The author does not say.

Lançon may not write much about the new space and time in which he and an unsuspecting France found themselves (he also proves remarkably restrained in characterizing the attackers who killed his friends and gravely wounded him), but he does have a few things to say about a novel depicting the near-future Islamization of the country.

In Michel Houellebecq’s Submission, French voters of varied persuasions rally around and ultimately elect a fictional moderate Islamist as president in order to stymie the presidential aspirations of his opponent in the run-off, real-life rightwing politician Marine Le Pen. Insofar as both the Charlie Hebdo outrage and Lançon’s own book are concerned, Submission emerges as germane in more than the evident thematic sense. For one thing, it hit the stands the very day of the attack. Consider, also, the following: Libération, the daily newspaper for which Lançon serves as a culture critic, had just published his review of Submission; he was slated to interview the author for the same publication a few days later; Houellebecq was on the cover of that week’s edition of Charlie Hebdo; and everyone in the Charlie conference room was talking about the book when Lançon arrived.

So how does the author react to Houellebecq’s explosive story? “I laughed a lot as I read Soumission,” Lançon recalls, referring to the book by its original French title. The reason for this is intriguing. He believes that, at the end of the day, with “its coyly downplayed provocations” and its counterintuitive depiction of a robust Islam restoring to grandeur a long since effete France, Submission qualifies more as dystopian fantasy, albeit of a decidedly arch sort, than ominous prophecy. He is almost certainly right.

Besides, he has more pressing concerns, especially once he recovers enough to move out of the rehabilitation-focused second hospital in late 2015 and regains his independence and mobility. One such matter is of particular interest, in that behind the otherwise prosaic choice of where to sit or stand in a crowded subway car may lurk an unseemly consideration. Having survived a deadly shooting by young male jihadis of North African descent, Lançon discovers that he is wary of Arab-looking youth. So much so, in fact, that he feels impelled to steer clear of them.

Yet he refuses to succumb to this new and disquieting urge. “It wasn’t normal, at least for me,” the author observes, “to fear all Arabs less than thirty years old whom I might run into.” Indeed, while understandable, the fear is irrational. That Lançon should recognize as much and act accordingly lends Disturbance a stirring quality. As a bonus, the whole affair imparts a salutary lesson: Whatever the space and time we find ourselves in, it behooves us to hold fast to reason, and aspire to fairness.

July 29, 2020

Rayyan Al-Shawaf is a writer and book critic in Malta. His debut novel, When All Else Fails, has just been published by Interlink Books.