Q and A: On Reimagining the New Testament as an Allegorical Horror Story

/In the spectacularly imagined Jesus and John, Adam McOmber has conjured a Lovecraft-esque ‘New Weird’ re-imagining of the New Testament as a novel of allegorical horror.

John, a fisherman from a rural village on the shores of Galilee, is tasked with protecting the risen body of his lover who was crucified for disrupting Roman order in the city of Jerusalem. And then the novel gets really interesting as the pair travel to a mansion in Rome known as the Gray Palace. With an eye toward Christian Gnosticism and Pagan dreams, McOmber seizes control and queers the classic story retold to so many of us every spring. The journey of John and Jesus is about devotion and the incalculable longing one experiences when one has everything one wants and yet, not quite enough. A central figure asks John, “Which do you prefer?” But how does one reply to such a question in a world without binaries? For The National Book Review, McOmber spoke with long time friend, Brian Leung about, blasphemy, glam, and the queer imagination.

Q: It might be true that I’ve read everything you’ve published, or nearly so. We’ve known each other for a long time, and above all else, I find you to be a playful writer and thinker. I don’t mean that in the sense of child’s play, but more that your imaginative self reconfigures everything from “the real” into magical props. In this way, Jesus and John is horror and fantasy built from your sense of play, and it has me thinking about Diane Ackerman’s Deep Play when she writes that “Above all, play requires freedom. One chooses to play. Play’s rules may be enforced, but play is not like life’s other dramas. It happens outside ordinary life, and it requires freedom.” How does her observation resonate with you as person Adam and as writer Adam?

A: I believe passionately in the concept of play both in life and in art. And I agree with Ackerman that play is not easy to come by. I’ve trained myself to step away from the ordinary as much as possible, to view the so-called real from what I hope is an uncommon vantage point. I have a strong sense of the absurd and the queer, and I also have an aversion to what many people would call “regular life.” I want to celebrate the strange, the weird, the unnatural. But as Ackerman says, there is a necessary component of freedom in all of this too. I notice many of my friends—especially on social media—repeating the same ideas, using the same agreed upon language. This, to me, is the opposite of that necessary playful freedom. It’s a kind of thought-cage honestly. I’ve considered various ways to better address the thought-cage. Jesus and John speaks to some of those concepts, as I’m trying to provide strategies for escape.

Q: Oh, “thought cage;” that’s an interesting term. This book is certainly uncaged. Which leads me to ask what is the history of your grounding in Christianity, and have you written a blasphemous book here, or how would you characterize the novel’s Weird reframing of Christianity’s central holy figure?

A: Blasphemy isn’t really on my radar. I can’t take a word like that seriously, you know? It feels archaic and empty, like the Catholic Church with its shiny jewel-encrusted surfaces and its impossibly dark uber-basement. A word like “blasphemy” makes me immediately say: “Who cares? Get out of my face.” This reaction comes, in part, from the fact that I grew up gay in a small Christian town in Ohio. That was a mess, honestly. It’s not an experience someone should have to endure. But many people, of course, are still forced to endure it. I knew that I had to find a way out for myself, both physically and mentally. The Weird is one way out; it’s become a kind of spiritual hammer for me. I use the Weird to break through surfaces, to shatter what Lacan calls the Symbolic Order, the structures imposed upon us by culture. Jesus and John is one example of a queer spiritual hammer. It wants to break the current order and move toward the Real—the thing that can never be seen or touched, though we sense it’s there around us all the time. I read a lot of theory about Jesus as I wrote the novel, and the Jesus I created became, for me, a kind of labyrinth. He can’t really be known. He’s an absence, but at one point, he was a presence. I suppose I made a kind of personal Jesus here, a Jesus who embodies my own searching. Hopefully, He’ll hold meaning for readers as well.

Q: I’m interested in this idea of your “personal Jesus” as connected to your own history in Ohio and the genesis, no pun intended, of this story. The paratext calls the novel “a postmodern gnostic gospel.” I suppose that makes you the implied Gnostic author. Talk a little more about how you manifested your personal Jesus through this gospel.

A: When I was in college, I read Elaine Pagels’ The Gnostic Gospels. It was one of those books that blew my mind—the idea that there were these other texts written around the same time as the texts in the Bible and that some of them might have been included in the Bible if not for the literalist take of the “editors.” The Gnostic Gospels are so strange—Jesus has a twin, there are dragons. And most importantly, perhaps, the creator god who makes the world is actually a deceiver. We are all currently living inside his lie. There’s a more powerful God out there somewhere, a truer God. This felt like an excellent metaphor. Jesus and John attempts to peer into the black box of whatever happened two thousand years ago. It’s my attempt at searching for something truer. The Jesus in my novel is introduced to his apostles as a kind of question. They are constantly trying to make sense of Him. John makes sense of Him in one way—as a lover—and Peter makes sense of Him in another way, as the leader of a rebellion. But really what’s really happening is that the initial question Jesus poses becomes an echo. There is no real answer. Everyone gets lost in the question.

Q: Leviticus 19:31 warns something to the effect, “Regard not them that have familiar spirits, neither seek after wizards, to be defiled by them: I am the LORD your God.” Do you see any irony in the fact that the Biblical Jesus performs some level of wizardry and that your novel, Jesus and John, transforms Christ into an even stranger spirit than what he becomes in the Bible? And, I suppose, on top of all this the author, you, is performing a wizard’s trick in upending John and Jesus’ story?

A: My version Jesus is a strange spirit, in part, because I am a strange spirit. My own experiences, both as a boy in Ohio and as an adult in Chicago and Los Angeles, have made the world seem slippery, less real than it may seem to other people. In terms of magic or wizardry, the Apostle John who narrates the novel doesn’t say that Jesus performs any of the miracles we normally ascribe to Him. A reader who is familiar with the New Testament will likely bring those preconceptions to the book, but no miracles are actually mentioned in the text. The only thing miraculous that this Jesus does is raise Himself from the dead, and when you read the book, that act doesn’t seem all that miraculous. In terms of my own opinion on wizards, I have no problem with them. Occultism is my jam.

Q: So, no harm will come to a believer who reads this novel? You are making no attempt to alter their faith and how they conceptualize a virgin Jesus as having died for our sins?

A: I’m not really concerned about anyone’s faith. The process necessary to have faith is alien to me. I suppose I can understand it on some level, but really it seems quite “other” in the end. I’m honestly not interested in trying to harm anyone’s faith or change it. Instead, I wanted to try to figure out how to make sense of this big immovable thing called Christianity for myself. It’s such a looming artifact in my own history. I was surrounded by it, trapped inside of it, much like how Jesus and John are trapped inside the house called the Gray Palace in my novel.

Q: There is the kick ass story aspect of this novel, and there also some surprisingly emotional touches. The novel is filled with a sense of longing, for example. Without giving too much away, it strikes me that John has quite a dilemma. There is a man that he is devoted to who likely can never fulfill his desires. Then, there are “options” let’s call them, which carry a weight not dissimilar to Peter’s multiple denials about knowing Christ.

A: I love novels that value story. I’m rereading The Talented Mr. Ripley right now and I’m, once again, so impressed by how Patricia Highsmith weaves such a tense and compelling plot. I find myself wanting to quit whatever I’m doing and return to Ripley because I want to know what’s going to happen next. That’s an effect I’ve tried to achieve in Jesus and John as well. I want the reader to feel pulled into the weirdness, to want to follow these characters. Desire is one way of achieving that effect for me. John, like all of us, is a desiring being. He has lost his beloved, Jesus. And rather than walking away, he’s still following Him around, searching for meaning where there either is no meaning or the meaning is too complicated for him to understand. Over the course of the novel, John encounters other possible ways to fulfill his desires. There’s a handsome Roman soldier. There’s an apocalyptic cult. He makes choices. He opens doors. Trouble ensues.

Q: Anyone who has followed your career recognizes your seemingly limitless abilities of speculative invention, but Jesus and John is raised to a whole other level. I’m going to coin a genre term here for the novel, “Biblical Steampunk”. But I want you to tell me what the definition of that term is. Maybe give me an example from the book.

A: Oh man! Okay, I’m game. The Biblical part is straightforward enough. I tried to recreate something that resembles the “Biblical Age” for at least a portion of this novel. I did a lot of research, trying to move the setting away from what we’ve seen in movies and television. The Steampunk part of your genre assessment is more complex. I agree that there is a punk or countercultural sensibility to the novel, a kind of middle finger to certain norms. Jesus and John is also Steampunk in the sense that it reimagines the technology of ancient Rome and Jerusalem. It presents a retrofuturistic vision. For instance, there’s an elevator in the novel. Elevators of a sort actually existed in ancient Rome, but seeing them depicted is surprising. There are many technological effects like that to be found in Jesus and John, little surprises intended to disrupt a comfortable sense of the “historical.”

Q: Thinking of “certain norms, as you put it, why does Jesus get top billing here? He strikes me as a supporting character, a Prometheus in John’s even greater story.

A: I agree, and yet I also think that John believes himself to be a secondary character. Jesus is his beloved but also a kind of master. Even in death, Jesus remains John’s motivating force, his plot. When they walk, John trails behind. Jesus always chooses the direction. I contemplated this image again and again as I wrote. Jesus wanders and John follows. He can’t help himself. There’s a kind of horror in this, following the corpse of your boyfriend around forever. But perhaps this is something we all do. We follow mirages, objects we have imbued with great meaning. But do they actually have meaning in the end? That’s a question John grapples with. Where is meaning to be found? Figuring this out will, perhaps, help him locate some kind of agency.

Q: And if this is John’s story, it’s less like Jesus Christ Superstar and more like Velvet Goldmine. If you recall, you and I saw that movie together in Bloomington, Indiana, at the Von Lee, in 1998. Do you see the connection I’m making with your novel and the David Bowie/Glam Rock era? Is John the curious reporter?

A: I do remember that, very fondly. I agree that John, as a disciple, or perhaps as the disciple, is indeed a kind of curious reporter adrift in the “glam” world of Ancient Rome. He follows the risen Christ, his one-time lover, through a mysterious labyrinth of shimmering, hyperreal signs, and he does his best to make sense of those signs, just as he tries to make sense of his own complicated desires. Todd Haynes’ Velvet Goldmine and perhaps his Far from Heaven are good exemplary texts for the tone I’m trying to strike. Jesus and John is a novel interested in solemn, almost funereal surfaces, but beneath those surfaces are these roiling emotions—feelings of loss and resentment, of confusion about how to move forward. In his collection of essays, K-Punk, Mark Fisher defines the glam impulse as a “hyperbolic/parodic identification with the big Other.” I think that too is a fitting description of what I’m trying to do in Jesus and John. As I wrote the book, I embraced the notion of parody, flipping the New Testament on its head, turning it inside out. I think John too understands that he is not part of the world in which he’s forced to exist. He wears the sandals and the robe, sure. He looks the part. But he’s not some pious figure. He is, instead, our existential guide through the darkness. He simulates but also complicates what we think we know about the “Apostle John.” I listened frequently to Pet Shop Boys’ “It’s a Sin” as I wrote about him: “Father, forgive me, I tried not to do it/ Turned over a new leaf, then tore right through it/Whatever you taught me, I didn't believe it...”

Q: We’ve mentioned film and music. What are three or four surprising texts you discovered in the making of Jesus and John and how did they shape your telling of the story?

A: Bart D. Ehrman’s Jesus Before the Gospels and Misquoting Jesus were both instrumental in helping me think about history versus myth. Ehrman also helped me understand something about current New Testament scholarship. H.P. Lovecraft’s “The Rats the Walls” and Gaston Bachelard’s The Poetics of Space helped in terms of thinking about occult architecture and the significance of what I will call “internal landscapes” or “mansions of the mind.” And, finally, Grace Krilanovich’s The Orange Eats Creeps helped me think about how to modernize the novel, to disrupt some of its historical conventions in interesting ways.

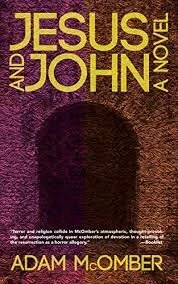

Q: All that helped you make the inside of a book. On the outside, readers will be confronted by the fact of a dark and ambiguous doorway in the novel’s cover. It serves as a kind of tonal overture to perhaps the central set of images in the novel when John decides to enter a mysterious house in Rome. To lay it all out there, when John steps in, is he actually coming out? That is, again avoiding spoilers here, do the strange events in that house track descent or ascent for John’s understanding of his desires?

A: The doorway image on the cover was created by the Australian artist Matthew Revert. I loved it the moment I saw it, as I think it speaks to many of the novel’s themes. If you look closely at the image, it’s not actually a doorway at all; instead, it’s the shadow of a doorway. There is, in fact, no door. No way out for either the characters or the reader. Everything in the text is perpetually revealed as a simulation, a shade. I love too that, in reality, an open door cannot possibly have a shadow. A state of openness isn’t a physical object. It’s an empty space. And yet we are confronted with the doorway’s shadow here. I think, as you say, that John is confronting many scenarios in this story that are not possible according to the laws of his society or according to the laws of contemporary Christianity either. When he enters the Gray Palace, he’s moving toward some truer form of understanding, both of himself and of his beloved Jesus. I think of the story less in terms of verticality—a traditional ascent toward Heaven or descent toward Hell—but more in terms of a deepening, an infinite passage through doors that both exist and cannot possibly exist. Movement toward something more profound.

Q: Let’s circle back, a little bit, and come at the source material from a different direction. Buckle up. The novel implies that human culture, maybe Western culture, is built coral like, mythology on top of mythology. John tells us at one point,

Tales of exotic creatures were common enough. My mother, in her sleepless nights, had described the animals named by the Greek traveler Herodotus: the dog-headed men and the giant golden ants, the one-eyed cyclops and the feathered griffins, yet this worm did not seem like a creature from some foreign land. It seemed instead the sort of impossible beast that could not exist. Could not have ever existed.

A few years ago, Neil Gaiman received some positive attention for Norse Mythology in which he retells, surprise, stories from Norse mythology. Gaiman is famously imaginative and certainly could have conjured his own Norse-ish mythology stories. Your source material, I suppose, is the Bible and the Gnostic texts. But, why tie yourself to these when you could have invented your own dude impossibly dedicated to a messiah and with a story unencumbered? How would that have changed the acid trip this novel takes us on? Why do writers find it irresistible to imagine through the lens of iconic source materials? And please do not mention Wicked in your response.

A: In order to understand the symptom, you have to take a closer look at the disease. Most of my writing stems from an examination of my own symptom and the various “diseases” given to us by culture. I recently gave a craft lecture about the concept of “celebrating your symptom.” I asked the audience not to fear their symptom, but to find a way to dance with it instead. Jesus and John is, for me, an example of that dance. I had a great deal of fun writing the book. I came out the other end really liking John and Jesus, really liking almost everyone in the novel. I enjoyed these figures and learned from them. I’m glad I took the trip. I’ve always said that I have no use for kitchen-sink realism. I don’t care about “slice of life.” Instead, I want to uncover cultural artifacts, to place them on the shelves of my weird traveling museum. Jesus and John are on the shelf now. Who’s next?

Brian Leung, author of Ivy vs. Dogg: With a Cast of Thousands!, World Famous Love Acts, Lost Men, and Take Me Home, is a past recipient of the Lambda Literary Outstanding Mid-Career Prize. Other honors include the Asian-American Literary Award, Willa Award, and the Mary McCarthy Prize in Short Fiction. Brian’s fiction, creative nonfiction, and poetry have appeared in numerous magazines and journals, including the previous iteration of Story. He is the current Director of Creative Writing at Purdue University, and his forthcoming novel, What a Mother Won’t Do (C&R Press) will be published in 2021.