Q&A: A Modern-Day 'Miracle': Reporting on the 12 Thai Boys Trapped in the Cave

/The world focused on a small province in northern Thailand in June 2018 when the Wild Boars Academy Football Club, a teenage boys soccer team, was stranded for 18 days inside a cave they had been exploring with their coach. A monsoon hit and high waters prevented their escape.

An international team of thousands, including over 100 divers, rescued the boys and their young coach in a complex process that involved pumping more than 1 billion liters of water out of the caves and anesthetizing the boys for their perilous, diver-guided, journey to safety, while an enormous camp of helpers and onlookers waited.

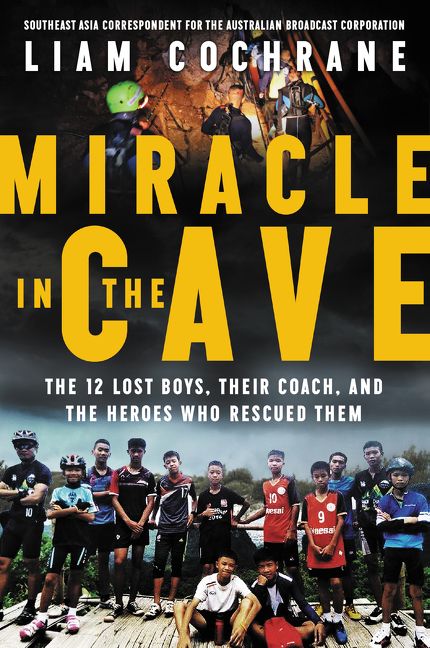

Liam Cochrane, Southeast Asia Correspondent for the Australian Broadcast Company, has written a vivid, meticulously researched book, Miracle in the Cave: The 12 Lost Boys, Their Coach, and the Heroes who Rescued Them (HarperOne/HarperCollins), focusing on the boys in the cave, as well as the complex rescue efforts involving more than 10,000 divers and experts drawn to the scene.

A former managing editor of the Phnom Penh Post, Cochrane is based in Bangkok. He met with The National Book Review’s Caroline Kaplan to discuss reporting on the boys in the cave, writing his book, and the unique challenges of politics and journalism in Thailand.

Q: Am I right to think that social media, particularly Facebook, helped you in your reporting, and more generally in getting the boys rescued? For instance, the amazing chef who used Facebook to bring a very famous monk to the cave to help save the boys?

A: Some of the key public moments of the rescue come from Facebook things. One of, if not the most, interesting interviews was the one I did with the chef who had the dream about the princess and calling the famous monk “Kruba Boonchum” to the cave. And he comes, and it’s a huge deal.

Q: Yes, the monk gives red string bracelets and blesses all the rescue operations teams. It seems like the thousands at the rescue site were really moved by the monk — and all because of the chef’s widely shared Facebook post.

A: Unfortunately, I could only put a little bit of the chef’s story in because most of what we talked about was even more bizarre -- about the dark spirits that visited her for many years — it was just unbelievable and fascinating. So, the chef’s post on Facebook, which perhaps on first glance seems a bit nutty, or not relevant, did actually have a tangible effect in bringing this monk to the cave, which bolstered the spirits of the families and the rescue workers. and was very deeply felt by Thais. I was aware he was there and was very revered, but didn’t know at the time how important it really was for superstitious or mystical Thais.

Another really useful thing was the Thai Navy SEALS Facebook page. They used their Facebook page during the rescue, and the wife of the SEAL commander did a lot of that. She was lovely. We met her and had a quick interview with her. She was one of the only women in the cave, throughout the whole thing. It was a very low- key scene in there, and it was a very strongly female scene outside the cave.

Facebook was huge, across Asia but particularly in Thailand. And towards the end, one of the only firm, credible sources we had was the SEALS Facebook page. There were lots of rumors about how many boys had come out, but until either Governor Naransak or the SEAL’s Facebook page confirmed it, we were never really sure.

Q: In terms of communication with Thai speakers, government and civilian, did you rely on translators?

A: I’m quite used to translators. Jum was with me at the cave, she works for the ABC, but then just by coincidence Jum was on leave for most of the time I was writing the book so that’s how I got Nat in. I hadn’t worked with her before, but she is fantastic, and Am as well. They’re right up there with the top fixers and producers in the country. They’re shit hot.

Languagewise, obviously I’m working through them so often I’m being led by them, depending on them absolutely, not just for facts, but also for the flavor. Nat, a main fixer, did a really good job of that. Particularly in interviews, like with the Grandpa who gave us the wonderful folk stories about the mountain, getting all that color, it comes through language. It was the same with the interview with the chef. It’s a slow process, but I was working with the best in the country.

Q: Details, such as how the boys got their nicknames, snacked on sugary drinks and sticky rice from the carts around their soccer field and filled their weekend schedules with tutoring and soccer practice, made the book so alive. I teach middle school boys and girls, so it just felt so specific, true and real to me. How did you capture what happened before you arrived on the scene on the tenth day? And how did you go about constructing the narratives about the boy’s lives pre-Tham Luang?

A: Hard work and research. That was a big challenge to go back and piece together what happened from all the different angles. The key challenge was trying to secure an interview with the boys. Once that interview happened, they provided detail about what actually happened. Little things like how they went in, and singing a little song as they walked into the cave.

And so, I ask: ‘what was the song? I was thinking it was going to be something really cool, but he was singing “now we’re walking in to the cave dah dah dah” but it is kind of lovely because that’s what kids do, which brought authenticity to it. On the process, because I wrote the first draft in seven weeks I knew I couldn’t really go down too many blind alleys or dead ends.

So, I just started with a big butcher’s paper and put in the center “interview with boys.” And around that kind of John or Rick (the eccentric British divers), and Richard Harris (the anesthesiologist who administered the sedatives to the boys), in concentric circles around there. So that was my plan of who I wanted to talk to. And from there it was a matter of getting all the fixers and asking: “How can we do this?” Then I had to line up as many interviews as possible.

Q: The number of different characters and personalities involved in the rescue mission was astounding. Your narrative puts at its center an American (Josh) who is fluent in Thai and happened to operate a rock-climbing business near the cave. He was a liaison between westerners and Thai government officials. How did you develop connections?

A: Between the Thai and international figures? That was a really interesting element to the story, potentially a somewhat controversial one. Going into the book, I was keen to tell the truth but to do it in a way that was kind to people, because everyone was there doing their best to get those kids out.

I don’t think there is any doubt that there were certainly misunderstandings, some gaps between the Thai military and the foreigners, and between different groups of foreigners involved, which is understandable. With military and civilians, there’s going to be a communication gap.

Q: Even when people are still speaking the same language, communication between military and civilians can be complicated. When thousands of people were at the site, speaking mainly Thai, while others were there speaking English, misunderstandings happen.

A: Josh played a huge role and I only found out Josh’s role quite late in the research, and it was fascinating. And it answered a bunch of questions about what went down. About how and when the decision to dive (as opposed to other rescue strategies) was made and why.

The whole thing was very much like a jigsaw puzzle. There were a lot of characters and a lot of scenes, and originally I had a straight chronological timeline. I was pretty much trying to get down to the minute of what happened when, and in the end with some excellent advice from the editor, we moved some things around and grouped them.

Q: It seems like much is happening simultaneously, at the rescue site and all-around Thailand. You capture the shifts in influence and power in rescue effort, and deal with Thai celebrities raising funds, cave diving shops around the world sending gear, and military involvement from three different countries. The Australians played a big role.

A: The Aussie angle was actually more difficult than you’d imagine. The Australian Federal Police declined to give an interview. It was a bit frustrating because they did play a wonderful role and had no reason to kind of keep it to themselves. But that’s their culture.

Q: it’s interesting that Dr. Harris [the heroic Australian doctor who spent three days in the cave on the rescue mission] declined to speak, because I feel like the scenes of him speaking to the boys and going through the sedation procedures are quite fleshed out.

A: The bits that contributed to Dr. Harris’s characterization was public, there were one or two tweets that were really important. He gave some seminars back in Australia after it all happened, and one of the doctors in the audience tweeted a slideshow, a photo and some information. And that was the first confirmation we had of specifically which drugs were used. That was very sensitive and quite secretive at the time.

After that, we could definitely say the sedatives were ketamine injections and Xanax, and an anti-saliva agent, which was genius.

So, you are absolutely right. It was small crumbs to try to get a picture of him. After the book was out, he sent me a message via Facebook and said, “just read the book, really enjoyed it, congratulations.”

And I wrote back and said, “did I get anything wrong?” Because as much as I did to put it all together, I wasn’t there --in the cave, or behind the scenes -- for most of it. So, I was still nervous that I might have screwed up some important detail. But he replied “nothing significant” so that was very reassuring.

Q: Were you nervous about some of these sensitive moments coming to light, and how do you feel the reception has been so far about some of the sensitive details?

A: There were a couple of things that were sensitive. But the sedation of the boys, I don’t think was something that needed to be sensitive because it saved their lives. It’s easy to say that now, because it worked, and I think we should say what happened. The sensitive issues regarding the King’s interest in the rescue of the Wild Boars and any discussion about royal issues in Thailand is something you have to be careful with because of the strict laws. In this case, the King’s contribution was very positive. So, I felt it would be okay to discuss it. And fair to give credit where credit was due, because the royal representatives played a very quiet, but influential role in making things happen.

Q: Chapter 27 takes place after the boys are rescued. It’s titled, “Hunting the Wild Boars” and is largely about the post rescue media circus. How did you balance wanting an exclusive story with the boundaries of ethical journalism?

A: We just did what we felt was right. And you know we took a bit of a risk. Because we got quite exclusive access to a boy and his family. We were there two nights after the Wild Boars got out of hospital and were there listening to his story. We had this amazing exclusive and no one else got an in-depth chat with the boys. But the agreement was, we weren’t there to report it. We were there as guests of the family. So, it was only later on, getting the father’s agreement, asking, “Can we use that, it would be important” and he agreed. So, no there wasn’t really pressure on us, the way there was pressure on other networks, particularly the Americans. Which you know, did get nasty.

Some of the Thai producers who were working for various networks are friends and were told not to talk to each other, because they work for competing agencies. As I mention in the book, we all wanted the interviews. We all wanted to talk to the kids. That’s what we were there for.

Q. You put getting that interview at the center of your butcher paper outline.

A: That’s it. I can only imagine the pressure that some people were under from their bosses, screaming at them to do whatever it took to get that exclusive. And that’s pressure that I wasn’t under. So, I wanted to cut some people some slack. But at the end of the day there are ethical guidelines.

Q: Just to be sure, the book has come out in Australia, but under a different title: The Cave. Why?

A: HarperOne, which is an offshoot of Harper Collins, publishes the American version and they wanted to package it differently. For the American markets, they felt that having “Miracle” in the title was going to be a good thing.

Q: That was an interesting switch, because there’s a moment in the book where a Brit diver says, “this wasn’t a miracle, this was hard work.”

A: Yes, and I agree with him.

Q: As a foreign correspondent in Thailand, what stories are coming up that you’re excited to follow? The possible upcoming elections for Prime Minister.

A: The election. The long-postponed election and return to some kind of democracy in Thailand is going to be interesting and perhaps something that will play out over years, as opposed to just the next few months. The coronation is going to be fascinating, one more step in the transition to King Rama X. Overall, across Southeast Asia, in the five Mekong countries that I cover, there’s sort of a shift towards more authoritarian rule. Myanmar was looking very hopeful for a while there but genocide of the Rohingya people, of course, is a huge cause for concern.

Politically things are pretty tough in terms of democracy, freedom and human rights. But there’s always great things happening, and there are always people doing wonderful things.

In this video, Cochrane explains Thai nicknames:

Caroline Kaplan is a Princeton in Asia teaching fellow at Deebuk Phang Nga Wittayayon School in Phang Nga, Thailand.