Q&A: A Legendary Reporter On His Book on the 1960s, Filled with Heroes and Villains

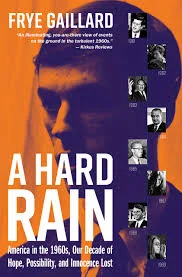

/In his fine new book A Hard Rain: America in the 1960s, Our Decade of Hope, Possibility, and Innocence Lost (NewSouth Books), Frye Gaillard makes a personal connection to the people, events and influences of one of the most momentous decades in American history. With the 1960s still reverberating powerfully a half century later, the work is a primer for the young and middle-aged and a reflection for those old enough to have personally witnessed that tumultuous time.

A Hard Rain tells the stories of heroes and villains, of soaring success in landing on the Moon; of devastating sorrows in the assassinations of two Kennedy brothers and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.; of the social movements that inspired women to greater equality and African-Americans to claim the civil rights they had been long denied.

Just listing the names of those who had lasting impact on American life shows the monumental task Gaillard faced in trying to capture how it felt to live in those times. In this 704-page mountain of reporting and research, he reminds us of the culture of the time--an extraordinary change from the previous decade—with the music of the Beatles and Jimi Hendrix; the conscience of Thomas Merton and the Berrigan brothers; the conservative voices of Barry Goldwater and Billy Graham and the singular impact of diverse figures such as Rachel Carson, Mister Rogers, and Andy Warhol.

Gaillard is the author of more than 20 books on Southern culture and history, including Watermelon Wine; Cradle of Freedom: Alabama and the Movement that Changed America; Journey to the Wilderness: War, Memory, and a Southern Family’s Civil War Letters and, most recently, Go South to Freedom, and in his long career as a journalist and author, Gaillard has won numerous literary awards and honors.

He is now the writer-in-residence at the University of South Alabama and the John Egerton Scholar in Residence at the Southern Foodways Alliance at The University of Mississippi, and corresponded from his home in Mobile, Alabama with The National Book Review’s Timothy J. McNulty who recommends that readers of Gaillard’s excellent book also look to Spotify for “A Hard Rain Reader Soundtrack” playlist that will help transport them back to those joyous, exciting and often shocking days.

Q: Your decade runs from Kennedy to Nixon with great achievements accompanied by an unresolved war, racial tension, environmental fears and deep political vitriol. Substitute the names Obama and Trump and the rest sounds familiar. If you were to write a book about the 2010s thus far, how would you subtitle it?

A: Depending on what happens between now and 2020, I might subtitle it “The Rise and Fall of America.” I've heard a lot of people say something like, however bad it seems right now the 60s were worse. I don't agree. I was overjoyed in 2008 when Barrack Obama was first elected. It was as if the greatest promise of the 60s, the kind of America Dr. King spoke about, had come to fruition. But the racial backlash against this brilliant black man was one of the most disheartening realities of my lifetime, followed by the rise of Trump, and the ongoing poison of Fox News.

In the ‘60s, until the assassinations of 1968, there were people like King and RFK who embodied our most audacious hopes, and even those whom some of us regarded as villains -- LBJ because of the war in Vietnam, or Richard Nixon for a whole lot of reasons, were multi-dimensional figures. Johnson was a great civil rights president, and Nixon was, in many ways, a statesman who normalized relations with China. Trump is more like Wallace as we knew him in the 60s, a man who sows division for his own benefit. It's horrifying.

Q: You distill stories from many sources and mix the immediacy of journalism with the calm reflection of history. What decisions did you make about including or dismissing accounts of events or people?

A: There are always decisions that have to be made in telling a story, and there are certainly other events and people whose stories could have been expanded or included. Some I've learned about since the book was published. But hopefully there is enough here for readers to know that I've aimed for as much breadth and depth as I could while trying not to let the story sprawl. It was the most difficult thing I've ever tried to write.

Q: Many books focus on just evolving politics, why did you choose to combine the influence of music, literature, art and movies? Did anything surprise you? Can you give examples?

A: I wanted to include those cultural dimensions because that was how I remembered the times. There were surprises, but mostly in the form of little details - like Betty Friedan and her friends writing out the founding principles of NOW (the National Organization for Women) on a napkin; or a Black Panther organizer in Chicago whose name was -- I'm not kidding -- Robert E. Lee, working to build a coalition with young and radicalized white Southerners now living in Chicago whose caps were emblazoned with the Confederate flag. I also did not expect to be writing about Mister Rogers or astronauts reading from the Book of Genesis on Christmas Eve, as they became the first human beings to witness an earthrise.

Q: To absorb the significance of events and people of an entire decade and to make it personal seems ambitious if not exhausting. Why did you undertake it?

A: It was pretty exhausting. But this was a decade that made such a huge impression on my life. I went from being a kid to a young reporter, with a life-changing interlude in college. I had chance encounters with people like Dr. King and Robert Kennedy and shared in the grief as we lived through the assassinations -- the Kennedys, King, Malcolm X, Medgar Evers; the Birmingham church bombing. And, of course, the War in Vietnam. I was so affected by all of this that I almost HAD to write it. And finally, there seemed to be such lessons and warnings for today -- the lessons of idealism and hope, the warnings against cynicism and despair.

Q: In terms of the writing and reporting mechanics, how did you start off? Did you enforce a discipline on your research and writing?

A: I had written about some of this before. The first chapter, for example, on the sit-ins. The detailed memories of some of those participants set a high standard for the rest of the book. I had to try at least to put a human face in the story; to describe how it felt, as well as what happened. Hopefully, the book has its share of feeling and heart.

Q: Yes, but for those who might want to write their own synthesis of a personal time of their life, how did you go about your research? Libraries? Google? Asking friends about their recollections? Gathering letters? You even put together a playlist to accompany the book, including the title from Bob Dylan's song. I imagine the process of discovery and selection must have both arduous and fun.

A: I kind of did all of the above. I had a research assistant, a terrific student of mine named Justine Burbank, and she spent a lot of time in libraries digging out newspaper and magazine articles about events I wanted to make sure I understood. I also read a lot of secondary sources that dealt with specific parts of the story -- a lot of biographies and such about major characters like Dr. King or the Kennedys, but also about figures I did not already know as well: Gloria Steinem or Betty Friedan or Cesar Chavez or Rachel Carson. And then there were interviews. . . Arduous and fun is a good summary.

And yes, we did put together a Spotify playlist that includes songs mentioned in the book because music was so richly integral to the whole decade.

Q: In that vein, you acknowledge, among many others, the work of David Halberstam who wrote The Fifties, as stirring your thoughts about writing this book. Could you list five writers who were major influences?

A: David Halberstam was always a writer I admired. I had already read books like The Best and the Brightest and his compact biography of Ho Chi Minh. A few years back I read The Fifties, and thought, huh, maybe I should try this on the 60s. I did not try to be David Halberstam, of course, but he was the writer who set me to thinking. I've also been a fan of Doris Kearns Goodwin and her biography of LBJ was especially influential on my thinking. Marilyn Young's book, The Vietnam Wars, was hugely significant in my understanding of the war. It was both passionate and well written and her views were similar, but more fully informed than mine when I began the work. Because Robert Kennedy was so important to the narrative, I was glad to have Jack Newfield's deeply felt RFK: A Memoir, and Evan Thomas's more skeptical biography. With regard to John Kennedy, I found a similar balance between Schlesinger's A Thousand Days and Larry Sabato's The Kennedy Half Century. I admired and read again David Garrow's Bearing the Cross about Dr. King and of course, The Autobiography of Malcolm X, including Alex Haley's afterword. All those books were especially important. But there were others.

Timothy J. McNulty is a veteran journalist, a retired lecturer at Northwestern University and a former teacher of creative non-fiction writing at the University of Chicago. His long career in national and foreign news coverage included roles as both a war correspondent and White House correspondent. He has traveled to all 50 states and reported from more than 65 countries. He was one of the first American journalists to live in Beijing. As the Middle East correspondent, he worked in Beirut and Jerusalem and upon returning to the U.S., he reported on social and political policy making in Washington for more than a decade. McNulty opened the newspaper's Atlanta bureau and traveled extensively through the South and became the national affairs correspondent the Tribune’s Washington Bureau. He was White House correspondent in President Ronald Reagan’s last year in office and for the full term of President George H.W. Bush. In 1992, McNulty won the White House Correspondents Association award for journalistic excellence for a series on the impact of satellite television on presidential decision-making and diplomacy. A senior editor at the Chicago Tribune for many years, McNulty served as the newspaper’s public editor from early 2006 until leaving the newspaper in August 2008. McNulty was the national reporter for the Tribune’s 1985 series on the emergence of an urban underclass, which won the Robert F. Kennedy Journalism Award and the Sidney Hillman Foundation Award. The Chicago Tribune awarded him its prize for distinguished reporting three times: For his contribution to reporting on Tiananmen Square, coverage of the Israeli siege of Beirut, and for the suicide/killing of more than 900 cult followers in Guyana.