REVIEW: A Rapturous New Oral History of 'Angels in America'

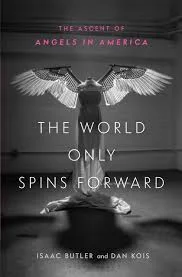

/The World Only Spins Forward: The Ascent of Angels in America by Isaac Butler and Dan Kois (Bloomsbury)

By Janice C. Simpson

Oral histories can be a lazy way of doing journalism. A reporter plunks down a recorder in front of a series of people who shared a common experience, later plucks out the juiciest parts of what they said and voilà, the job is done. Which may explain why oral histories of every pop cultural phenomenon from Woodstock to Baywatch now vie with Top 10 lists as a surefire way to lure readers into magazines and websites.

But there is nothing lazy about The World Only Spins Forward: The Ascent of Angels in America, the prodigiously reported and deeply engaging book by Isaac Butler and Dan Kois that traces the evolution of Tony Kushner's landmark two-part play about the AIDS crisis. This oral history is, like the play it chronicles, a masterpiece of its art form and it makes a persuasive argument that Angels in America helped change the way this country views gay people and gay people view themselves.

The World Only Spins Forward started out as a magazine story for the online publication Slate back in 2016. But the response was so strong that Butler, a theater director and writer, and Kois, a culture editor at Slate, have expanded that piece into this 448-page book that arrives just in time for the first Broadway revival of the plays since they premiered there in 1993.

The book's very first chapter signals that The World Only Spins Forward intends to be more than frivolous chatter. Its main voices include Barney Frank, the first openly gay congressman; Cleve Jones, founder of the AIDS Memorial Quilt project, and Robin Haueter, a spokesman for the activist group ACT UP, each recalling the horrors of the early plague years when thousands died from the then-fatal disease and millions more feared not only death but the shame that often came when family members or employers discovered they were gay.

Recalled Haueter, "One of the hardest things for people who didn’t live through that time to understand about gay culture was what it was like to be underground. In a big city like New York, you could hang around gay people and live in a pretty gay world and feel like you were 'out,' but the reality was you were in a bubble. The real world, no one was 'out' in the larger world."

But as the AIDS body count rose, plays like William M. Hoffman's As Is and Larry Kramer's The Normal Heart began to reveal the struggles of the gay community. Located in San Francisco, an epicenter of the plague, but unable to get the rights to either of those works, the small but socially conscious Eureka Theatre Company commissioned Kushner to write an AIDS play for them. The playwright already had a title, drawn from a poem he'd written for a friend who'd died from the disease: Angels in America. He subtitled it "A Gay Fantasia on National Themes."

After three years and much angst—Kushner had so many ideas he wanted to explore that the play had to be broken into two parts—the first reading was held in 1989 in a tiny theater on San Francisco's Mission Street. Word of the plays' intellectual precocity and unapologetic gayness spread quickly. People with AIDS came in wheel chairs to see them. Workshop productions at the Mark Taper Forum in Los Angeles and the Juilliard School in New York were set up, as was a full production at the Royal National Theatre in London.

Kushner relentlessly and ruthlessly revised the plays at every stop, weaving together the multiple storylines of Prior Walter, a man recently diagnosed with AIDS and his fickle lover Louis; Joe Pitt, a closeted gay Mormon and his Valium-popping wife Harper; Roy Cohn, the real-life lawyer and confidante of both Joseph McCarthy and Donald Trump who denied his homosexuality even after contracting AIDS; the ghost of Ethel Rosenberg, who was executed for being a Communist spy during the Red Scare that Cohn helped engineer; and, of course, the Angel who crashes through Prior's bedroom ceiling at the end of the play's first half.

Throughout the process, parts got cut or pumped up. Speeches were rewritten and then rewritten again. Actors for whom roles had been created saw them recast with others. Even Oskar Eustis, the dramaturge at the Eureka who had commissioned Angels, co-directed the L.A. workshop and become one of Kushner's closest friends, got replaced by the New York director George C. Wolfe when the plays moved to Broadway.

Those eventually Pulitzer- and Tony-winning Broadway productions fall at the midpoint of the book. The remaining half chronicles subsequent productions, including the HBO mini-series directed by Mike Nichols and starring Al Pacino as Cohn, Meryl Streep as Ethel Rosenberg and Emma Thompson as the Angel; the experimental Dutch director Ivo van Hove's stark version played against a soundtrack of David Bowie songs, a controversial student production at Catholic University and the current revival which played to great acclaim in London last year and has now transferred to Broadway with Andrew Garfield as Prior and Nathan Lane as Roy Cohn.

Butler and Kois, who talked to over 250 people, track every step of the journey, from the NEA official who gave Kushner his first grant to work on the play to a chorus of contemporary playwrights like Pulitzer finalists Jordan Harrison and Stephen Karam and Hamilton's Lin-Manuel Miranda who grew up reading Angels and cite it as an inspiration for their work.

The book's authors also seem to have found every interview Kushner ever gave and pepper their narrative with excerpts from them, from letters written by and to the playwright and from contemporaneous diary and journal entries kept by people associated with the various productions.

Seemingly everyone who ever crossed paths with Kushner or his plays shared their memories. A few starry names like Pacino and Daniel Craig, who played Joe Pitt in the London production, are no-shows but Streep chimes in as do Garfield, Lane and Jeffrey Wright, who played the compassionate nurse Belize both on Broadway and in the miniseries.

When there are multiple versions of a particular event, Butler and Kois let each person have his or her say. Inevitably, some of the more quotable sources get to go on more than need be. And despite identifiers in each chapter, it can be hard to remember exactly who all the speakers are. But the overall effect is like eavesdropping at a reunion of old friends once the boring folks have left and the good booze has been poured.

Particularly winning are the interludes devoted to each of the major characters in which actors who played those roles—from Stephen Spinella, who originated the role of Prior in the first Eureka reading and played it straight through the Broadway production, to the stars of community theater showcases—talk about their interpretation of Kushner's creations and how portraying them affected their own lives.

The recollections aren't all sweetness and light. Disagreements are remembered. Disappointments are acknowledged. Kushner's sometimes bruising protectiveness about his work is a running theme. "He's legendarily tough on the director he's worked with over the years," recalled Tony Taccone, the Eureka's artistic director, who was booted from an early incarnation but is mounting a production at the Berkeley Repertory Theatre this spring.

Still, Angels clearly meant a lot to the people who worked on it over the years and their awe of the play and lingering devotion to it resounds through their comments. David Marshall Grant, who played the closeted Joe in the original Broadway production, came out during that run and considered giving up his acting career when the show ended. "I didn't think there was anywhere else to go," he told the authors. "I felt a part of something that was way beyond me."

The World Only Spins Forward is a full-throated celebration of the remarkable work that made Grant and so many others feel that way.

Janice C. Simpson directs the Arts & Culture Reporting program at CUNY's Graduate School of Journalism; she also writes the theater blog Broadway & Me and hosts the BroadwayRadio podcast "Stagecraft.”