REVIEW: John Banville's Fine Memoir of a Literary Life in Dublin

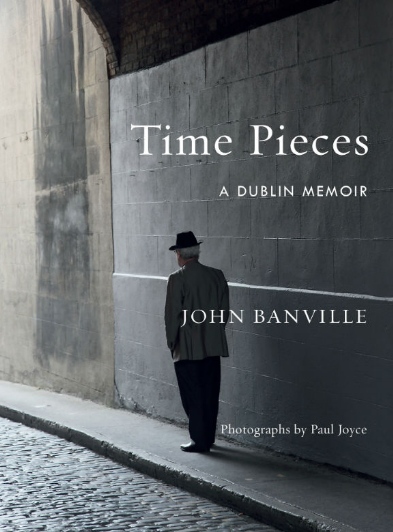

/Time Pieces: A Dublin Memoir

By John Banville

Photographs by Paul Joyce

Knopf, 224 pp.

By Robert Allen Papinchak

In Time Pieces, accomplished novelist John Banville manages to trap Dublin in amber and then, as in the Jim Croce lyric, put time in a bottle, forever uniting them in his memory and imagination. Banville -- a Man Booker Prize winner, the author of Mrs. Osmond and, as Benjamin Black, the writer of a series of mystery novels featuring Irish pathologist, Quirke -- seamlessly blends personal history with the story of Dublin to produce a rich non-traditional autobiography suffused with compelling descriptions and captivating anecdotes.

Now 72, Banville recalls a seminal recurring event in his childhood that shaped the rest of his life. Each year on his birthday, December 8 (the Holy Day of the Feast of the Immaculate Conception), he, along with his mother and sister, took the 80-mile train trip from his native Wexford into Dublin, the Christmas-bedecked city of “magical promise towards which [his] starved young soul endlessly yearned.” On his way there, the budding novelist imagined himself aboard the Orient Express as a “confidential agent” (a/k/a spy) on a “top-secret mission to the dusky and dangerous East.”

In Dublin, Danville says, even the rain is different, and “drops as fine as and as penetrating as neutrinos.” Once there, he spends his glorious birthday “jaunts” with his mother’s sister, Aunt Nan, who would have a lifelong influence on him. Her Mount Street flat became the residence of his protagonist, Quirke.

After a breakfast of “sausages, rashers, fried egg and fried bread,” there were stops for ice cream, the yearly purchase of a “ten-and-sixpenny wristwatch” which “charmed and fascinated” him, and an exchange of gifts (including another of his beloved toy guns). He left the city saddened because “something was ending, was being folded up, like a circus tent; was becoming, in short, the past.”

It is the past that is the overriding key theme to Time Pieces. Banville wonders, evoking Wordsworth, if the “child [is] father of the man,” then when “does the past become the past?” If the “present is where we live, while the past is where we dream,” then the past is “substantial, and sustaining.” It “buoys us up [like] a tethered and ever-expanding hot-air balloon.”

For most of the rest of the memoir, Banville is accompanied by developer Harry Crosbie (to whom the book is dedicated). He calls him Cicero, his enthusiastic and well-informed guide to “the hidden city.” In Cicero’s “little red roadster," they make stops to see the “carefully preserved frontage and side wall of the original Abbey Theatre;” the severed head of Admiral Nelson , which stood atop the landmark of Nelson’s Pillar until 1966, when an IRA bomb demolished it, leaving the hero looking like “a badly battered prize-fighter;” and the Iveagh Gardens, not far from St. Stephen’s Green, which includes a maze that is so mysterious it defies discovery. Their “whirlwind tour” culminates at the “airy confection of glass, steel and wood” that is the Great Palm House of the Botanic Gardens.

Gardens and parks, like pubs, hold a special place in Banville’s heart. It is in a park where Banville experiences his first throes of unrequited love. For him, parks and their gardens evoke a “magical timelessnesss.” They are the “quintessential public manifestations of the Enlightenment and its values.” Though “[w]e change, we age, we stay or move away, and in time we end,” a park “endures.” Banville still wonders if the girl he loved endures.

Dublin endures through its “most notorious” literary “’characters,’” Brendan Behan, Flann O’Brien, Patrick Kavanagh, James Joyce, W. B. Yeats, and Seamus Heaney. It is a city that had “more than its fair share of frauds, poseurs, and poetasters,” but it is also a “city of stories.” Banville chooses to tell a few of them, including ones about the stones of Georgian Dublin and the prostitutes he glimpsed in his aunt’s flat along with other “illustrious tenant[s]” like Yeats’s widow and daughter.

As Banville calls up incidents from his past to understand the present and its inveterate frozen timelessness, he also discovers something about art and its eternal presence. He sees art as a “constant effort to arrive at, or at least to approach as closely as possible, the essence of what it is, simply, to be.” Time Pieces concludes with Banville wondering, almost nostalgically, like F. Scott Fitzgerald’s “boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past,” what path time will take him on next. The reward for the reader of this fine memoir is that Banville has already provided an indelible image of his impressive footprints.

Robert Allen Papinchak has reviewed a range of fiction in newspapers, magazines, and journals including the New York Times Book Review, the Washington Post, the Chicago Tribune, the Seattle Times, USA Today, People, The Writer, Publishers Weekly, Kirkus Reviews, the New York Journal of Books, The Strand Magazine, and others. He is the author of Sherwood Anderson: A Study of the Short Fiction.