ESSAY: Fireflies in a Glass: Catching the Light After an Author is Gone

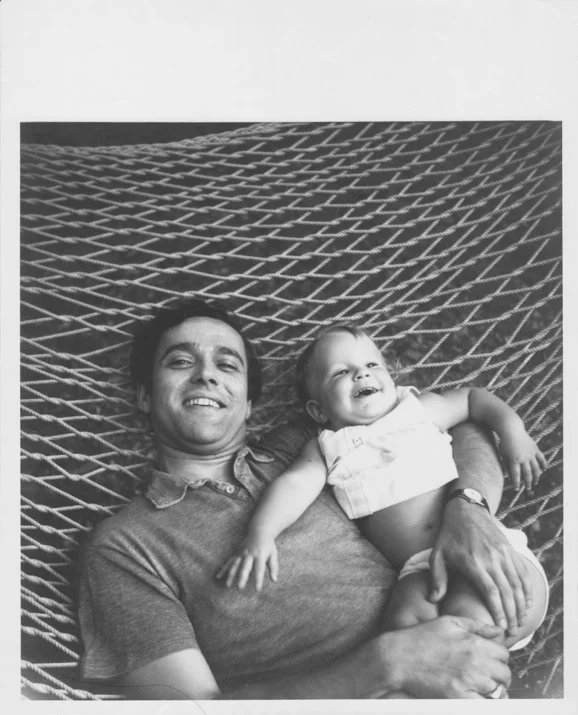

/In this photo, from the summer of 1969, Reynolds Price was 36 and Memsy was months shy of 2. It inspired Reynolds to write “To My Niece: Our Photograph in a Hammock,” published in Southern Review in Autumn 1972 and reprinted in poetry collections.

By Memsy Price

When my uncle, the author and English professor Reynolds Price, died in January 2011 he left behind a quasi-museum: his house, filled with paintings, sculptures, and the detritus of his steadfast devotion to eBay. He had lived in the house since the early 1960s and filled every available surface with objects. When he ran out of wall space he hung pictures on the kitchen cabinets.

He purchased the midcentury, split-level home in the woods with the proceeds from the movie option to his first novel, A Long and Happy Life. In the mid-1980s when spinal cancer and radiation treatments resulted in paralysis, he expanded the house with a wheelchair-accessible addition. He’d written the early parts of his 1986 novel, Kate Vaiden, before he got sick. He was supposed to die with that book unfinished. But Reynolds lived, and the novel went on to win the National Book Critics Circle Award.

Reynolds published twenty-five more books of fiction, nonfiction, poetry, essays, and plays in his lifetime. He was a successful and prolific writer, and a demanding but loving—occasionally even doting—uncle. Born eight years before my dad, his only brother, I christened him during my toddlerhood with a not-quite-grandfather nickname: Uncle Tuff.

As anyone who’s been left crumpled in the wake of grief understands, the endless logistics associated with death can feel particularly burdensome. My father, William Price, and my mother, Pia, tirelessly tackled logistics, including the epic task of what to do with more than half a century of accumulated possessions: his house, his wheelchair, his furniture, his many collections (including rare volumes of poetry by John Milton, Wedgwood busts of authors, movie stills, Russian icons, a pantry shelf groaning under the weight of every spice he’d ever purchased).

There was also the question of what to do with his work. Reynolds left behind thirty-eight books, several plays, two songs he co-wrote with James Taylor, reams of correspondence, royalty statements, and an unfinished memoir under contract with Scribner. My dad was named literary executor, a second full-time job on top of clearing out his brother’s house. Reynolds had appointed him but never mentioned it; dad learned the news when he read the will. When I asked my father about it he said, “I guess he trusted I’d do fine.”

In the immediate aftermath of an author’s death, a literary executor must notify agents, publishers, and others associated with his or her work. The executor also has to determine the best course of action for published works (in all media) and any unpublished work and papers, including correspondence. In my uncle’s case, these tasks weren’t as complicated as some—I’m thinking of someone like Maya Angelou, whose legacy includes books, movies, plays, television shows, recordings, and a line of merchandise—but they were thorny enough that I thought my work experience in book publishing would be of help. I knew how to parse contractual language and decipher royalty statements, so I volunteered to help manage my uncle’s literary estate in consultation with my dad, who readily agreed.

Dad started with Reynolds’ papers and correspondence, which were the most straightforward in legal terms. Years earlier, Reynolds had arranged for his papers to go to the David M. Rubenstein Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Duke, the university where he taught for more than fifty years. It’s a rich collection—he traded letters frequently with Eudora Welty and Stephen Spender, two of his mentors. The list of his other correspondents reads like an eclectic anthology of 20th century literature: W.H. Auden, Edward Albee, Pat Conroy, James Dickey, Ralph Ellison, Toni Morrison, Anne Tyler (whom Reynolds taught in his first year as a professor).

Reynolds had transferred correspondence and drafts of his manuscripts to Duke over the years, and Dad followed suit. Less straightforward was what to do with his published works and unpublished memoir. He hadn’t left us explicit instructions regarding either. His final months were grim, marked by intense pain and heavy medications. His literary legacy was a low priority compared to managing his pain and round-the-clock caregivers.

After his death, we thought he’d want Scribner to publish a posthumous version of his memoir-in-progress but didn’t know whether it would accept an unfinished manuscript. Dad and I forged ahead without a map.

Dad’s experience as an archivist and his deep knowledge of his brother’s life and work combined with my publishing experience made us a good team. I’d never worked as my father’s colleague, and doing so was a transformative experience for both of us, a chance to appreciate each other as committed professionals instead of child or parent.

Scribner did want to publish the unfinished memoir and Midstream debuted in the spring of 2012, with a foreword by Anne Tyler and an afterword by dad. With a posthumous publication, there’s no author to book on a reading tour or for interviews with Charlie Rose. Nor was there an author to make and approve revisions or sign off on design or jacket copy.

Dad and I had to make hundreds of decisions along the way: approval of cover art, what the cryptic list of photographs I retrieved from Reynolds’ computer meant, what his biography should say on the back flap. We tried to channel my uncle but understood we’d never be him.

The memoir received a range of reviews, a traditional part of the publication process that could proceed even posthumously. My favorite review, from Open Letters Monthly, was mixed but, for me, contained an almost perfect observation: “He generated a small handful of these wondrous little memoirs, capturing some glint of himself in each like fireflies in a glass. Midstream is the last flicker of that self readers will ever get; they should treasure it.”

The published work isn’t the same as the version that would have appeared if Reynolds had lived. But it’s a firefly in a glass, and Anne and dad’s memories of a writer and person they admired and loved are fireflies too. My hope for all families and publishers left to make decisions on behalf of authors is that they can rest easy knowing they can’t be the author, but will do the best they can.

The last time I spoke to my uncle he was bedridden and had finally resorted to the morphine he’d resisted as long as he could (because it dulled his sharp intellect). But the surgeries, radiation, and decades in a wheelchair wrecked his back, and his vertebrae were essentially scraping against each other. I had gone by his house to take supper to Reynolds and his assistant, Braden, before my family and I left on a holiday trip. I talked quietly with Braden in the kitchen while Reynolds slept in a morphine doze. As I got ready to leave, he called me to his bedside. He thanked me for the food, and I leaned down to give him a kiss goodbye. “Don’t be gone too long,” he said, “don’t forget about your old Uncle Tuff.”

I assured him I wouldn’t, but I never saw him conscious again. I miss him, even now. I wish I could tell him that my daughter loves David Copperfield. I think he’d be glad I finally finished that MFA I talked about for years and that I cooked his favorite spaghetti carbonara for our extended family in his kitchen on the night he died. I’ve not forgotten my old Uncle Tuff. I hope in the decisions dad and I have made as executors, we’ve remembered him well.

About Reynolds Price

Reynolds Price was born in Macon, North Carolina, in 1933. He earned an A.B. from Duke University, and in 1955 he studied English literature at Merton College, Oxford University as a Rhodes Scholar. After three years and a B. Litt. degree, he returned to Duke, where—for over fifty years—he taught, becoming the James B. Duke Professor of English. His work has been translated into seventeen languages.

Price died on January 20, 2011. His home, where he had lived for nearly fifty years, was a testament to his many passions. Shortly after his death, the photographer Alex Harris documented his house and many collections.

In August 2017, George F. Thompson, in collaboration with The Center for Documentary Studies at Duke, will publish Dream of A House: The Passions and Preoccupations of Reynolds Price. That book, edited in collaboration with the photographer and memoirist Margaret Sartor, includes a selection of Harris’s photographs, excerpts from Price’s works, and essays by Harris and Sartor. An exhibit of selected photographs from the book and artifacts from Price’s collected papers will be held at the Rubenstein Library at Duke University from July through November 2017.

Memsy Price is a writer and editor in Chapel Hill, North Carolina. In 2016, she received an MFA in Creative Nonfiction from Goucher College. Price recently completed a memoir, Siren Song: A Story in Two Southern Worlds, that tells the story of her two Southern families, one Neapolitan and one North Carolinaian.