REVIEW: A Gruesome Child Murder, as Told by a Victim of Childhood Sexual Abuse

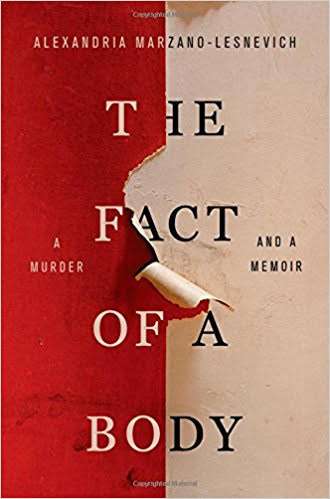

/The Fact of a Body: A Murder and a Memoir by Alexandria Marzano-Lesnevich

Flatiron Books, 322 pp.

By Madeleine Blais

There is much to admire about Alexandria Marzano-Lesnevich’s first book, The Fact of a Body: A Murder and a Memoir, including its ambition and its more than occasional felicities as a piece of prose.

The author has set for herself a daunting task, seeking to find the shared humanity and narrative communality in her own story and the story of a serial child molester and confessed murderer.

On a scale of who automatically makes a sympathetic character, Ricky Langley would easily attain a rank of zero. A runt with jug ears, he has come into this world as a result of what appears to be marital rape: bed-ridden and in a body cast, on a huge cocktail of drugs, including painkillers and subject to multiple X-rays, his mother becomes pregnant with him while recovering from a car accident that killed two of her other children. Blighted from the beginning, Ricky life limps along in the shadow of these losses and further deprivation. An obsession from an early age with his dead brother Oscar leads to hallucinations while still a child.

The author first learns about Ricky as a Harvard law student during a summer internship in Louisiana. She watches a tape in which he confesses to the murder of six-year-old Jeremy Guillory on a February day in 1992. Opposed the death penalty since childhood, at that moment she admits, “I want Ricky to die.”

Ricky’s victim is a neighbor who, with his mother’s permission and BB gun in tow, makes the fatal mistake of paying an after-school visit to a young pal at a house where Ricky, who supports himself at the nearby Fuel Stop, is a boarder.

No one else is at home and it is only a matter of minutes before the child is lured to an upstairs bedroom, smothered, in all likelihood sexually violated, and then hidden in a closet for three days before the authorities discover the body. When the child’s distraught mother appears at the house late in the afternoon of her son’s disappearance, Ricky Langley proceeds to take cruel pleasure in assuring her that he has not seen Jeremy, to the point of offering her a phone so she calls relatives to see if they know of his whereabouts, and sharing an alcoholic drink with her.

Marzano-Lesnevich, on the other hand, comes from an intact family with four children. Both parents are lawyers. She grows up in a beat-up but spacious Victorian in Tenafly, New Jersey, a good town, unlike the ones nearby “with crimes” and with “school statistics we whisper like warnings.” A maid does the laundry. The author spends summer in Nantucket until her father says he is bored with that and they go the France instead.

Yet her family had its own challenges including a father who hides his disappointment with drink, and a mother who refuses to acknowledge it. Both parents preferred, in lieu of candor, a veil of secrecy and silence. Marzano-Lesnevich has her own lost sibling: an older sister who was third in a set of triplets who died at five months whom she doesn’t learn of until years later. Even more traumatic than that loss were the visits at night to her bedroom by a supposedly beloved maternal grandfather in which a creaky staircase is the herald of his hideous approach.

The author tries to be fair:

So before my grandfather gets any higher on the staircase, before he climbs into our bedrooms, know this: He was not all bad. He was a man who delighted in the power of stories, who when my mother and her brothers were young would take home a projector from his film-cutting job and thrill them by turning their living room into a theater. He knew how to make children laugh and he always had a candy sucker in his pockets or a tin windup dog from the dime store. He was the finest artist I ever knew, a painter and a sculptor. He taught me to draw. He taught me what it was to look inward, to be quiet and thoughtful amid the world’s clamor. We were alike in this way, he and I. We were alone together in my family in this way. I loved him.

But then, during the molestation that follows, something shatters inside the young girl: her disembodiment is echoed in a startling image of her grandfather’s false teeth in a glass, “glistening like a sea creature.”

He warns her against revealing his dark desires: “I’m a witch. Don’t forget. If you tell I’ll always come find you. Always. Even after I am dead.”

Indeed, when her parents surmise the truth when they discover he has violated another daughter, instead of confronting him, the whole family goes out to dinner as planned, grandparents, parents and children, and the only repercussion is that he is never again allowed to spend the night under the author’s family’s roof.

Marzano-Lesnevich is left to grapple with the idea of forgiveness for the rest of her life. Among the most luminous moments in the book is the passage in which the dead boy’s mother Lorilei argues in court for mercy for her son’s killer: “As sure as I hear my child’s death cry, I too, can hear Ricky’s cry for help.” At least some of the author’s desire to blend the two stories comes from this woman’s remarkable compassion, a mystery the author tries to plumb.

In her desire to connect as many dots as possible, Marzano-Lesnevich hits a false note late in the book when she discovers that the killer and the boy’s mother were at the same high school at the same time and writes in a voice bloated with omen: “The future is coming, eleven years ahead. It sends its long low warning signal over the pages of this story.” A tendency to indulge in overstating her case in not the book’s worse flaw.

Marzano-Lesnevich’s work falters, dramatically, when she dishonors the distinction between the two stories and conflates the narrative threads. In one scene, the author dresses the killer’s mother in a housedress: “pink with tiny blue flowers, a smocked polyester collar with lace appliqued on it,” that she admits is imported from her grandmother’s closet. Much later, she revisits the same grandmother’s closet for yet another outfit for Ricky’s mom to wear. On numerous other occasions, she invokes this fictive sleight of hand, as when the dead boy’s mother is pictured talking to police before the body is found: “Let’s put her in a small room at the police station for this. From the ceiling hangs an overhead cone light like the one my parents had in the kitchen when I was growing up ….”

At one point, the killer’s father’s station wagon from the ‘60s reminds her of a family car that didn’t even exist until many years later. By the latter half of the book, a kind of ventriloquism takes over. The word “maybe” is used to usher in all kinds of scenes that might have occurred, but never did, at least never did with any evidence, which, if you think about it, is what most lawyers usually live for. Perhaps the most unsettling is when the author imagines Jeremy’s mother imagining her son at the age seventeen with Hallmark bromides: “He’d be sweet on a girl at the high school by now …”

A “note on source material” at the beginning of the book outlines the author’s reportorial strategy which includes the expected mix of archival research and direct interviews whenever possible, but she justifies these frequent fictive leap as an effort to layer her imagination “onto the bare-bones record of the past to bring it to life.” To her credit, she always makes it clear when such intrusions occur, but the conflations start to add up and clog the story rather than clarify it. The end result is a mish-mash that threatens to dilute the narrative thrust of both stories.

Paul Valery said, “All theory is autobiography” and Flaubert famously pronounced, “Madame Bovary, c’est moi.” Savvy readers of nonfiction are used to surmising, if only subliminally, the nexus between writer and subject: the shared kinship between Truman Capote and Perry Smith from “In Cold Blood” come to mind. But it is rare for the link to be stated so overtly.

Beverly Lowry’s Crossed Over: A Murder, A Memoir, published in 1992 resembles The Fact of a Body in its thesis. Set in Houston, this work examines emotional similarities between author’s eighteen-year-old son, killed in an accident, and 23-year-old Karla Faye Tucker who murdered two people with pick-axe. Loss and grief are the ultimate subjects of both works though Lowry is more circumspect about forcing the connectivity between the disparate storylines.

And yet, and yet, and yet: despite serious missteps in some of the story-telling choices, what remains for the reader of The Fact of the Body are two separate tales that possess undeniable power --- though it would seem, more so on their own.

Photo: Nancy Doherty

Madeleine Blais is Professor of Journalism at the University of Massachusetts Amherst where she serves as Honors Director in Journalism. She won a Pulitzer Prize in feature writing while on the staff of the Miami Herald’s Tropic Magazine and she was a Nieman Fellow at Harvard.

She is the author of The Heart is an Instrument, a collection of journalism, and In These Girls, Hope is a Muscle, which was chosen as a finalist in the category of general nonfiction by the National Book Critics’ Circle. Her memoir Uphill Walkers: Portrait of a Family was selected by the National Alliance for the Mentally Ill (NAMI) for its annual “Ken” book award and was also chosen as Massachusetts Book of the Year.

For twenty years Blaise has been Director of the Williston Writer’s Workshop Series at the Williston Northampton School, bringing in prominent writers to present to students and the public four times a year. She is also a faculty mentor in the Goucher College low-residency Masters of Fine Arts in Nonfiction program in Baltimore.

Her To the New Owners: A Martha's Vineyard Memoir is forthcoming from Grove Press in July.