Q&A: Brunonia Barry on her Modern Witch’s Tale, ‘The Fifth Petal,’ and Salem’s Past and Present

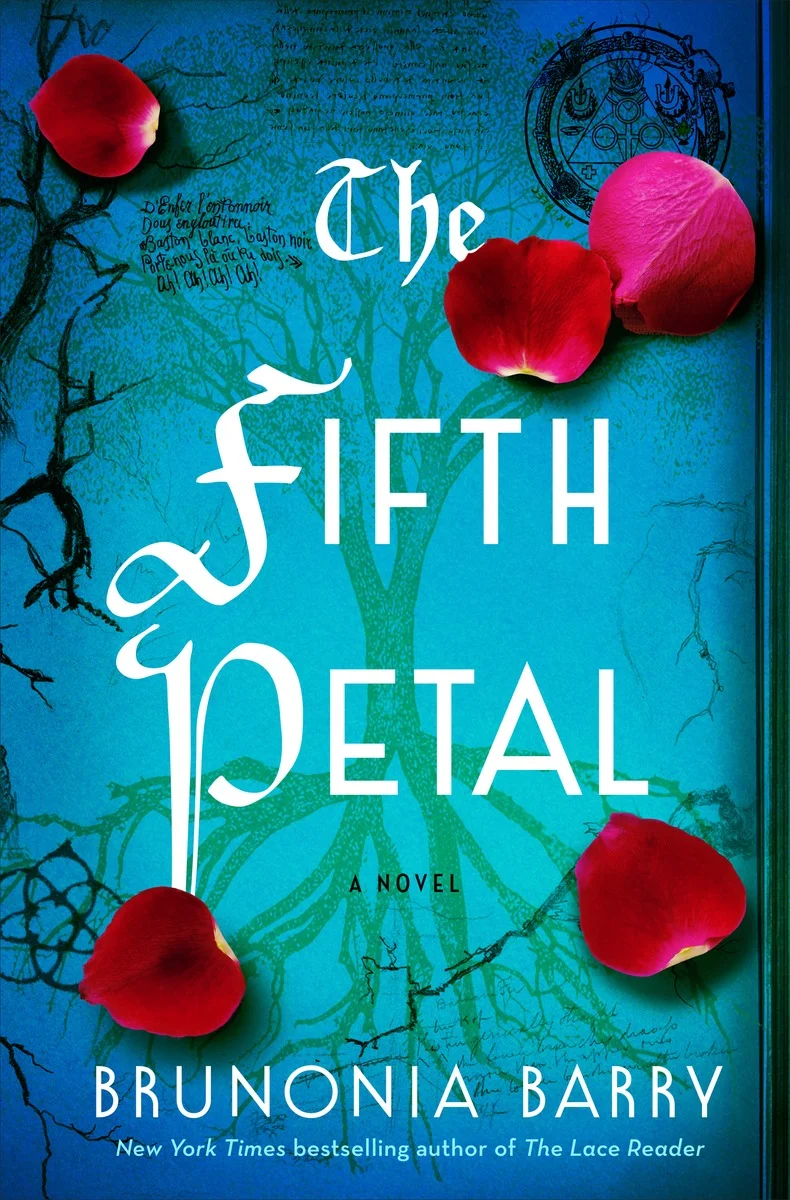

/The Fifth Petal is the long-awaited third novel from Brunonia Barry, the beloved Salem, Mass. storyteller. Barry made her debut with The Lace Reader (2008)—a rare example of a self-published title that became a New York Times and international bestseller when later released traditionally. Barry was the first American to win the International Women’s Fiction Festival’s Baccante Award; she is also the winner of New England Book Festival’s award for Best Fiction. Her works have been translated into more than 30 languages. Barry co-chairs the Salem Athenaeum’s Writers’ Committee and, with her husband, is the organizer of the Salem Literary Festival.

Q: What first inspired the idea for The Fifth Petal – and how do you see this work as representing an evolution of your storytelling?

A: In terms of my storytelling evolution, it was time for me to tell the story everyone expects when they think of Salem: the 1692 Witch Trials. But I wanted to do so in a way no writer had yet approached, that is a modern story that mirrors our dark history. There were no witches in Salem in 1692, but, ironically, they thrive here in great numbers now. Thousands of neo-witches and pagans from all over the world have moved to Salem to practice their religion, not in spite of 1692’s dark history but largely because of it. An alternative title for The Fifth Petal might be A Tale of Two Salems.

Living here, I am often struck by the opposing factions in our city. During the month of October, our population of 42,000 grows by almost 300,000 with tourists booking rooms years in advance to celebrate Halloween here. The locals are divided in sentiment about the influx. Merchants need to make a living on the tourist trade, but just as many Salemites would like to “ditch the witch,” forget our dark history, and simply move on. Every year at Halloween, evangelist preachers come to Salem to save the souls of the sinful revelers, preaching hell and damnation. So far, it has been a fairly peaceful coexistence, but it always makes me uneasy. I find myself wondering if the whole thing could happen again in Salem, and if so, what a modern day witch-hunt might look like.

Q: As a resident of Salem, tell us: in what ways does the collision of past and present create a unique atmosphere there– and how do you endeavor to capture that within your narrative?

A: History casts a very long shadow in Salem. You can’t wander our streets without discovering a history lesson around almost every corner, from the witch trials of 1692, to the China trade when Salem was the richest port in the New World, to the first blood of the American Revolution, which was shed in Salem. We are informed by everything that has happened here and suffer a generational guilt about the witch hysteria that is typical to places where such horrifying events have occurred. It would be almost impossible to forget our dark past; the tourists who visit Salem remind us of it every day.

Writing a fictional story about a real place can present some challenges, particularly in capturing its essence. For that reason, I have tried to treat Salem as a character in all three of my novels. But the Salem of The Lace Reader and The Map of True Places is not the same city as that of The Fifth Petal, which takes place fifteen years later. Salem has changed and grown in much the same way a real character might. As the cultural center of the North Shore, we have been discovered for our architecture, art, restaurants, etc., as well as real estate prices that are far cheaper than Boston’s, thereby attracting young professionals who commute into town. The influx is great for property values but bad for diversity, something Salem has prided itself on, an indirect reaction to the 1692 witch trials, when being different, or “other,” was a dangerous thing. In losing this diversity, we risk losing some of the tolerance we have celebrated over the years.

Q: In the book, there are contemporary deaths that appear to have historical roots. How is the community’s response a reflection of the sentiment that prevailed in the seventeenth century? Also, what are the lessons to be learned from the Salem witch trials that are both relevant and resonant still today?

A: What would a modern day witch hunt look like in Salem? It wouldn’t be the same, of course; we would never let that happen again here. But there are subtle similarities that occur any time anyone is persecuted for being “other,” and they are happening everywhere today.

Mental illness has always been one of the causes of persecution, and it’s the one I chose to focus on for this book. There is still such a stigma against seeking treatment. The state hospitals have closed (which was probably not a bad thing), but the promised community treatment centers that were supposed to replace them have never materialized. As a result, there are five times as many mentally ill in jails now as there are in hospitals and many more than that are homeless.

A few of those executed as witches in 1692 were mentally ill. I used the case of Sarah Good as an example in this book. Though diagnosis was difficult to come by, speculation says that Good was probably mentally ill, as was her daughter, Dorothy, who at 5 years old was the youngest of the accused and jailed, and though she was never tried or executed, the child was never the same after her incarceration and had to be cared-for for the rest of her life. Her mother Sarah’s illness went untreated, and as a result, she was hanged as a witch. There were other factors involved of course: Sarah’s outspoken nature, an inherited debt from her first husband, passed along to her second husband and causing tremendous hardship, reducing the family to homeless beggars.

The town’s treatment of Rose Whelan in The Fifth Petal, though perhaps more subtle, is a modern version of what happened to Sarah Good. Sarah’s daughter provided the model for Callie. And, of course, all three victims who were murdered on Halloween in 1989 were descendants of the five women hanged on July 19, 1692. Rumor and innuendo play the same part as they did in 1692, this time with social media intensifying and spreading the accusation. And in much the same way as events unfolded in 1692, Salem once again doesn’t recognize this witch hunt for what it is until it is almost too late. The lessons learned have their roots in the past, proving the old adage: those who do not understand history are doomed to repeat it.

Q: Your books incorporate magical realism and the paranormal. How does the suspension of disbelief play into this – and in what ways does interweaving fact and fiction help ground the story?

A: Most of the magical realism in the novel has parallels in quantum physics, and I believe that helps to ground the story. For example, the belief in non-linear time parallels Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle in which observation affects what is being observed. Things we often consider paranormal now will most likely be explained at some point by scientific theory. I’m sure that psychic knowledge, which I consider very real, can be explained by some as yet unmapped part of the brain.

Sound healing is another example. If sound can destroy (think of kidney stones being exploded by ultrasound), can it also heal? Music certainly has the ability to “soothe the savage breast.” And the magic image system of the trees in the novel comes from recent research into tree communication, which is being studied around the world. For anyone interested in the subject, The Hidden Life of Trees by Peter Wohlleben is a great source book. I’ve always wanted my stories to exist on two levels, to be explained by both mysticism and science, letting readers decide which rings true for them.

Q: You don’t adhere to the traditional book-a-year publishing schedule. How do you balance the need to sustain your audience with the need to fully cultivate your story?

A: I’d love to publish a book a year, but is just doesn’t work for me. My stories are quite complex and, though I generally start with a simple premise, they take a while to fully reveal themselves to me. I also confess to loving the research process so much that I may linger there bit longer than necessary. There is a single moment when I know the story is complete, but, deadlines aside, I can’t predict when that moment might come, not at the expense of the narrative.

I know this presents a particular challenge for readers, and so I’m trying hard to get started writing a bit earlier in the process, researching just what I need to know for the story and not letting my interest in the subject matter capture my attention in the same way it did with The Fifth Petal. The good news is that my next book, Bone Lace has a great head start, and I expect to have a first draft finished later this year, so it shouldn’t be as long a wait next time.

Q: Your first book, The Lace Reader, was initially self-published. Given that background, how do you see that platform (and the perception of it) as having changed over time – and what advice would you give to writers when considering what outlets to pursue?

A: When The Lace Reader first came out in 2008, the e-book platform wasn’t as well established, so we followed a more traditional route, publishing the book as a trade paperback. We hired an editor and a PR company, and we were lucky enough to find a distributor. There was still a stigma against self-publishing, and the process was expensive, which left little money for marketing. We had some good early reviews and were quickly picked up by a larger publisher who had the marketing budget it would take to make the book a hit, but it could easily have gone the other way.

For that reason, I never recommended self-publishing to other writers. There was just too much luck involved. But with the popularity of e-books, everything has changed, and self-publishing has become not only acceptable, but, I believe, a smart way to get started. Self-publishing in e-book format is a great way to launch a book, and I know that this is where agents and publishers are looking for new writers. That said, marketing is still a huge part of the process, and finding some kind of promotional hook is important. It is easier with non-fiction, but it’s important to fiction as well.

John Valeri wrote for Examiner.com from 2009 to 2016. His "Hartford Books Examiner" column consistently ranked in the top ten percent of all Hartford, National Books and National Arts & Entertainment Examiners. John currently contributes to The National Book Review, The News and Times, The Strand Magazine, Suspense Magazine, and CriminalElement.com. He made his fiction debut in Tricks and Treats, a Halloween-themed anthology published by Books & Boos Press last fall. Visit John online at www.johnbvaleri.com.