Q&A: Barack Obama Speechwriter Tells All (Spoiler: He's a Big Fan)

/When David Litt graduated from Yale with a major in history, he had little idea that his own words would one day enter into history. But after becoming entranced by a youthful, Democratic Senator from Illinois named Barack Obama, and pledging his life to Obama’s presidential campaign, Litt found himself rewarded with a job in the White House as a speechwriter. By his mid-20’s, he had worked his way into a senior position on Obama’s staff, writing the President’s monologues for the Correspondents’ Dinners, and, in what should be considered an even more impressive triumph, teaching the President how to pronounce “Chag Sameach” on Passover.

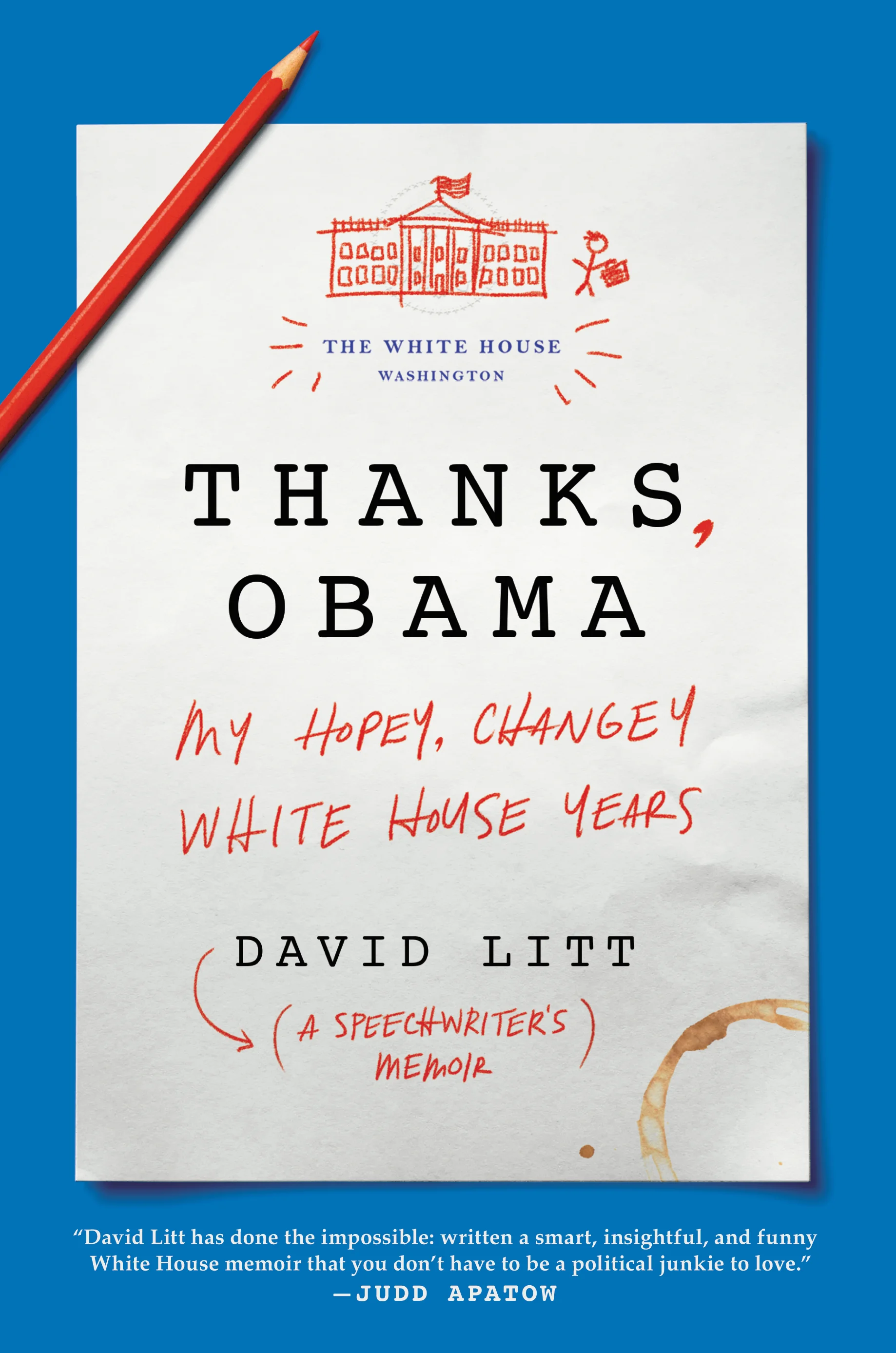

In his new book, Thanks Obama: My Hopey Changey White House Years, Litt chronicles his journey from wide-eyed college graduate to seasoned White House veteran, and the steps, missteps, and near-World War inducing disasters in between. The National’s own recent Yale graduate and history major, Noah Asimow, had some questions for David Litt, including his advice to a new generation of up-and-coming speechwriters.

Q: David, thanks so much for doing this! What were some of the unique challenges in writing a full-length book as someone who spent almost a decade working as a speechwriter, a business in which creative expression often plays second-fiddle to word limits and brevity? Did you enjoy writing about yourself and your experiences, or did the years spent writing for others, including President Obama, make writing a book in your own voice particularly difficult?

A: Everyone warned me that writing a book would be hard, and I was like, “Yeah, right. I wrote for the president of the United States. This is going to be easy!”

It turned out I was wrong and everybody was right. The most difficult thing about a book, as opposed to speeches, was thinking about the entire story arc – I was used to writing in 3,000 word increments. I’m really confident that the published version is a single, coherent whole, but it took five drafts.

Q: Many of the hilarious stories you tell about your time as a Presidential speechwriter could fall under the term “misadventures”- you give Obama a Gordian-knot of headphones and watch as he untangles them with a death-stare, you find yourself exposed, nearly-naked in front of all of your co-workers on Air Force One. Yet these follies all seem incongruous when told from your writing voice, a voice that is confident, powerful, and funny. How do you explain that the person who wrote myriad jokes for Obama’s Correspondents’ Dinners is the same guy who always seemed at a loss for words when talking to him face-to-face? Would you say that your writing voice is a more accurate representation of yourself, or are you like me; someone who can write a 20-page paper in a night but can barely tie his shoes when he needs to go turn it in?

A: I was always confident that I had the ability to do the work. It was everything tangential to the work that scared me. In other words, I truly believed that with enough effort and focus, I could write a great presidential speech. But remembering to wear a belt every day? Avoiding coffee stains on the paper that went to the president’s desk? Those things were not going to happen.

Q: Your sense of humor is one of the best elements of the book, and it clearly was integral to your career as a speechwriter. At what point in your life did you know you were funny? Do you find that your sense of humor comes through most vividly in writing, or are you someone who people consider funny in real-life as well? If not, what’s the difference?

A: I’ve always been either the kind-of-serious funny person in the room, or the kind-of-funny serious person in the room. The first time you meet me, I will almost guarantee you that you won’t find me funny. But I’d say I’m precise with my language, and that’s a trait most comedy writers and speechwriters share.

Q: Near the end of the book, you mention leaving the Oval Office and “never dreaming” of taking an apple from the bowl on the table, a symbolic power-move that would have felt quite out of line. But working as a Presidential speechwriter, did you ever feel you deserved an apple even though you were never allowed to have one? As in, was there ever a moment when you felt that your work was going unnoticed and unappreciated, and that you had to give up personal fame in exchange for almost complete anonymity? If you never felt you deserved an apple, who in Obama’s White House did?

A: All speechwriters trade ownership of the words for size of the audience, and it’s a trade I was certainly comfortable with (especially considering who I was writing speeches for!) If we’re talking metaphorical apples rather than literal ones, what I love about campaigns and public service is that there’s not a limited amount of responsibility to go around. I think all my colleagues feel, in some small way, that they personally did something to improve the country they care about. And they would all be right. So, apples for everybody!

Q: At the book’s start, you give “a note on facts,” clearly a necessity in the shadow of Trump. We are now almost eight months into his presidency, and the dysfunction in the White House becomes more apparent every day. How do you imagine Trump’s speechwriters feel about him? (If he has any at all, which is always unclear.) Has it been painful to watch these past six months unfold, knowing how much hard work went into Obama’s tenure? If so, what do you see in store for the future, of both Trump and the legislation he wants to either enact or repeal?

A: It’s been painful, not because I worked for Obama, but because I don’t think this administration shares America’s values. We’re going to get through this – we’ll protect democracy and make our union more perfect, just like we’ve always done. But putting the wrong people in power has consequences, and we’re going to have to live with them.

Q: Just as Trump has disavowed the media, he has also, time and time again, refused to use a teleprompter or script of any sort when giving speeches, claiming that these practices are the domain of career politicians. What do you think is the role of the speechwriter in the age of Trump? Does Trump have a point in saying that perfectly tailored speeches have watered-down politics, or does this make the role of good speechwriters, like good journalists, more important than ever?

A: I’d actually take issue with that. Trump frequently uses a teleprompter, and it’s clear he doesn’t really understand or believe the words written for him. So, he’s exactly the kind of politicians so many conservatives decried.

Q: Before working in the White House, you “imagined spending [your] twenties squeezing every drop of adventure from life.” Eight years later, you were wearing a suit to work every day and instead of climbing Himalayan peaks, you climbed bureaucratic ladders. Do you think that this is good advice for recent graduates who may not yet know their calling? Do you ever regret missing the chance to backpack through the Himalayas, even if you missed it to work in Obama’s White House?

A: I don’t think I made the wrong choice, but I certainly regret not getting to live multiple lives and spend one of them in the mountains. There’s nothing wrong at all with taking time to have some experiences right after college that you can’t have nearly as easily a few years later. But after you find yourself, find out what matters even more than yourself.

Q: Has it been difficult to re-adjust to a life outside 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue?

A: The strangest thing was the release of pressure I had forgotten even existed. Suddenly if I let myself down, I was only letting myself down. In some ways that was great! The flip side is that I didn’t get to be even a small part of these extraordinary moments. And I do miss that.

Q: If the right candidate came along, do you see yourself ever reentering the speech-writing business? You say in the book that your true love was campaigning. For Democrats, there are big elections coming up, not just in 2018, but 2020 as well. Is there anyone you could see yourself knocking on doors for right now? If not, what do you think the ideal 2020 presidential candidate would look like?

A: In September 2005 I don’t think anyone could have predicted that Barack Obama was going to emerge as the nominee in 2008. So, who knows? And I’m excited about not knowing. Let’s give lots of different voices and vision a chance to compete, and become stronger – I’m confident if we do the best one will emerge in time for the 2020 campaign.

Noah Asimow recently graduated cum laude from Yale University with a degree in history. While there, he was a Thouron Scholar, captained the Club Baseball team, and started an a capella group that exclusively sung nautical folk music (they called themselves The High C’s). Although he currently works for West Wing Writers as a speechwriting intern, Noah also has fond memories of umpiring, caddying, and the summer he spent working at the St. Louis Cardinals Hall of Fame and Museum--even though he grew up in Chicago, and is a die-hard Cubs fan.