ESSAY: Reading Thomas Wolfe in Italy

/

By Memsy Price

About a dozen of us assembled in the lobby of the Thomas Wolfe Historic Site in Asheville, N.C., when the guide announced the start of our tour. An enthusiastic guy, with the sort of Scotch-Irish Southern accent that pegged him as a native of the North Carolina mountains, he warmed us up with a broad smile and words of welcome: “Thank you for choosing to spend this beautiful spring day at My Old Kentucky Home” — using the name the old boardinghouse had when Wolfe’s mother, Julia, bought it in 1906.

Then he asked for a show of hands: “How many of you have read Look Homeward, Angel?” Nearly everyone’s hand went up. I read the book in college. A few years later I read You Can’t Go Home Again, The Hills Beyond, and The Web and the Rock during the six months I lived in Milan, Italy. All three books changed me, but it was You Can’t Go Home Again, one of his posthumous novels, that hit me in the gut.

As the tour progressed through the house’s warren of bedrooms, I recalled my youthful connection to Wolfe and his work, and how important his books became at a time when I struggled to understand where I was going and where I was from. I can’t go home again, I told myself during and immediately after college. But when I left Milan, having consumed Wolfe’s big stories and a lot of life, I wondered if I could.

Like Wolfe, I grew up in North Carolina and attended its flagship state university. I majored in English, he in Dramatic Arts. I often walked by the Wolfe memorial on campus—a bas-relief angel. Like him, I moved to New York City shortly after college.

I lived in Chelsea when there was still an A&P on Eighth Avenue where Debbie Harry sometimes shopped. I worked for a literary agent—a Frenchman, no less—and fancied myself part of the city’s literati. I took the subway to 23rd Street instead of the 18th Street station closer to my apartment so I could detour past the Chelsea Hotel and the plaques on its façade, honoring the musicians and writers who had lived there: Bob Dylan, Dylan Thomas, and Thomas Wolfe. I liked how their names could run together into one continuous name, Bob Dylan Thomas Wolfe. Wolfe’s plaque calls him a “Great American Writer,” and commemorates the years he spent living and writing in room 829.

* * *

My second summer in the city, I got an ear infection and went to the only doctor I could think of—the cardiologist father of a college friend—who, during my exam, noticed “a nodule” on my neck. Everything happened really fast after that, but also in kind of surreal slow motion; I shuffled around New York in a daze. I had a big a tumor on my thyroid, the “best” kind of tumor to get but still frightening. After a biopsy, the doctors concluded surgery was my best option.

I was smart enough to know I needed to go be with my parents in North Carolina. When I called my health insurance company to verify they’d cover the surgery regardless of location, the customer service agent asked me where exactly I’d have the operation. “North Carolina,” I replied.

“Hold on, hon,” she clipped, in a New York accent so thick it sounded like a parody of a New York accent.

When she came back, she asked, “Will you have the surgery in a hospital?”

Did she think we didn’t have hospitals in North Carolina? Was she picturing a guy with a pocketknife who’d take care of business out by the barn? Was somebody going to bust up a chifferobe?

I never figured out what she thought, but they approved the surgery.

New York seemed determined to suffocate me after I returned, and the July heat wilted my resolve. I had moved apartments by then, to a fifth-floor walkup in Murray Hill with no air conditioning and two roommates. The blades of the box fan in my tiny bedroom filled the space with cloying smells—yak butter, goat stew—from the Tibetan restaurant downstairs

I felt desperate to change my life. If I didn’t do it now, I told myself, when would I ever get the chance? One can become very sands-through-the-hourglass after a health crisis, even when it turns out okay. My desperation took the form of an ill-formed and idealistic plan: move to Italy and get a job.

My mother grew up in Southern Italy, and I had spent a summer during college studying Italian in Perugia and visiting her hometown, Sorrento. I decided I’d get a “real” job, not one where I had to wait tables, and it would be easy enough to find one in the publishing industry, which I had worked in in New York. The Italian publishing industry is in Milan, so I’d move there, where I didn’t know a soul.

* * *

In the winter of 1991, when I left North Carolina for visits to Paris and Brussels on my way to Italy, I didn’t have to show ID to get through airport security. I went to the bank in Raleigh to get travelers’ checks, which I signed in the presence of a banker and signed again when cashing them. My friends and family sent letters care of the American Express office in Milan while I tried to find work and a place to live. I would dutifully troop over there a couple of times a week to see if anyone had mailed me a letter.

I spent most of my first weeks alone. I walked the entire city. I’d buy a piece of focaccia studded with salty, purple olives and sit in front of the massive cathedral watching tour groups and beggars move back and forth across the building’s ornate, white façade. I found the American library, where I could read English-language newspapers and magazines for free. I wrote in my journal (at the time, I used “journal” as a verb) with a fountain pen and tallied every lira I spent.

I stayed in terrible, one-star hotels. My first night in the city, as I checked into a shabby place near the train station, the guy working the desk asked if I wanted to go have coffee. I declined, and holed up in my single room. A friend of a friend, a fashion writer I’d met in Paris, had scheduled a trip to Milan and told me to call her collect as soon as I got to town.

I don’t know how I had the foresight to mention the guy at the desk, but when I did she said, “I’m going to wait while you move every stick of furniture in front of the door to your room.”

When I demurred, she said, “He has a pass key.” In the middle of the night, I heard a key rattle in the door. The furniture prevented it from opening. I understood how lucky I was, but it didn’t make me any less concerned about finding a place to live. “It occurs to me,” I journaled, “that the kind of hotels I can afford to stay in are hotels where the towels and coat hangers are printed with the names of other hotels.”

I somehow found a job and a place to live. I got hired by a friend of a friend of the fashion writer to work at a small ad agency and sublet an apartment from an American woman named Carla, who had moved in with her Italian artist boyfriend.

I was so grateful to be in an apartment, with a narrow but sunny kitchen where I could make my own espresso. There was a wonderful bread store around the corner, where the owners were so kind about my improving Italian language skills. My conversational Italian was decent when I arrived, but my journals are filled with lists of the new words I learned every day: to iron=stirare, scommettere=to bet, fiancé or boyfriend=fidanzato.

I had unexpectedly left a boyfriend behind in the States. As I planned to start a new life, I accidentally fell in love. I went to Italy thinking he was the man I’d marry, and I almost did. In Milan, I missed him with the sort of longing that could only be described by a Bronte sister.

I made friends in the city. I shared an office with a young woman in her late 20s who took me under her wing and corrected my Italian in the most helpful ways. But she lived at home, with her parents and brother, and I went back to my empty apartment. My other close friends, two Irish girls working in Italy thanks to the newfound freedoms of an EU passport, lived across town and I saw them on weekends.

On weeknights, I made an easy supper—a spinach omelet or a dish of pesto pasta—and stared over my balcony railing at the sunset. Sometimes I listened to music but mostly I read.

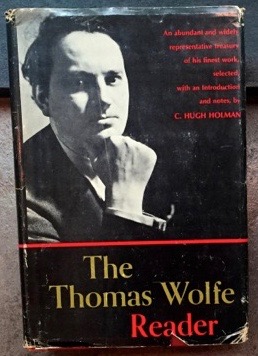

Carla left three cardboard boxes of books in the living room. I don’t remember the entire contents, but I read everything, including Lawrence Durrell’s Bitter Lemons and most of Edith Wharton’s novels. The real prizes in those boxes, though, were three big novels by Thomas Wolfe.

I put off reading them because I hadn’t loved Look Homeward, Angel. My journals show I tore through the Wharton books during April. Then, in mid-May I wrote, “Started Thomas Wolfe’s You Can’t Go Home Again. Totally took me (unlike Look Homeward). NC, NY, Europe. I feel in a way like it’s my book, too.”

* * *

This same feeling came flooding back as I walked around the Thomas Wolfe Historic Site, 25 years after writing in my journal. Sometimes the perfect writer finds us at exactly the right time. For me, a confused but determined girl from North Carolina feeling every kind of sickness there was—actual physical sickness, homesickness, lovesickness—I looked past the flowery and archaic language to find Wolfe giving voice to my nostalgia.

I loved George Webber, the protagonist who comes home to North Carolina shocked by the angry reception to his autobiographical first novel. I quoted him at length in my journal: his impressions of train rides, thoughts on the vastness of America, what it meant to George to be a writer. I copied down what Wolfe’s characters thought about being Southern. Passages like, “He knew that there was something twisted, dark, and full of pain which Southerners have known all their lives—something rooted in their souls beyond all contradiction.”

George Webber was lonely, too: “During all this time his life was about as solitary as any that a modern man can know. Loneliness, far from being a rare and curious circumstance, is and always has been the central and inevitable experience of every man.”

When I finished the novel, I wrote, “Cried at the end of this book, thinking of how things never are the same, how you can’t go home again and how profoundly painful that can be. But how good, too. To experience home as a new place, to be forced to find somewhere besides home because home isn’t what you thought it was. After the initial disillusionment, I suppose, comes grand perspective.”

* * *

As I sit now at my desk in Chapel Hill, looking back with the distance of time and age, I understand Wolfe helped me stay in Italy while I learned how to live on my own. It was the loneliest I’ve ever been but also the most courageous. And he allowed me to decide to come back to North Carolina—“Old Catawba,” he called it—where I’ve made my own grownup life and family.

I’ve never read another Wolfe novel, nor have I re-read any, lest I spoil the magic they created in Milan. I did later read some of his correspondence with Maxwell Perkins, Wolfe’s editor and literary executor. The last letter Wolfe ever wrote was a note to Perkins dated August 12, 1938, when the author sensed his approaching death. It’s a short letter, especially by Wolfe standards. He closed it by remembering the day he learned his novel, Of Time and the River, was a huge success.

Wolfe wrote: “No matter what happens or has happened, I shall always think of you and feel about you the way it was that Fourth of July day three years ago when you met me at the boat, and we went out of the café on the river and had a drink and later went on top of the tall building, and all the strangeness and the glory and the power of the life and of the city was below.”

No matter what happens or has happened, my memory of sitting alone on my Italian balcony—reading his big novels while hearing the buzz of Vespas, the ominous toll of the church bells in the campanile across the street, and the clanking of dishes as my neighbors cleaned up after supper—is as vivid as Wolfe’s Fourth of July.

* * *

Wolfe died too young, at 38. I’ve now lived a decade past that and, while visiting the Wolfe Memorial, I felt at home, even as conflicted as I am about living in North Carolina’s current political climate. What’s happened to our state? Where did the New South go?

I try and reassure myself that history operates in cycles, that bigotry has to lose in the end. I’m still that solitary young woman who found a way to love her home state even if she didn’t understand it.

In The Web and the Rock, Wolfe wrote, “Old Catawba is just right. They are not going to set the world on fire down there, neither do they intend to. They make all the mistakes people can make. They elect the cheapest sort of scoundrel to the highest offices they are able to confer. They have Rotary Clubs and chain gangs and Babbitts and all the rest of it. But they are not bad.”

In recent years, we’ve elected the cheapest sort of scoundrels to our highest offices. They’ve yanked the social safety net out from under thousands of our poorest residents and grabbed headlines with their outrageous, discriminatory legislation. My neighbor’s hay field is covered in buttercups; his grazing cows look like props in a pastoral theater set.

When my daughter attended her first Moral Monday protest at the General Assembly on a beautiful April afternoon, her determination shone with the fierce stubbornness of a teenager waking up to the world. My family isn’t setting the world on fire, but we’re trying to do our part. We make mistakes and try to correct them. Home, even on our bad days, is just right.

Memsy Price is a writer and editor pursuing an MFA in Creative Nonfiction at Goucher College. She was an editor at Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill back in the days when the publishing house’s office was in an actual wood-frame house in Carrboro (a P.O. box was kept in Chapel Hill). Follow her on Twitter at @memsyp