REVIEW: When Oneida, N.Y. was a Center of Utopianism, Eugenics, and Free Love

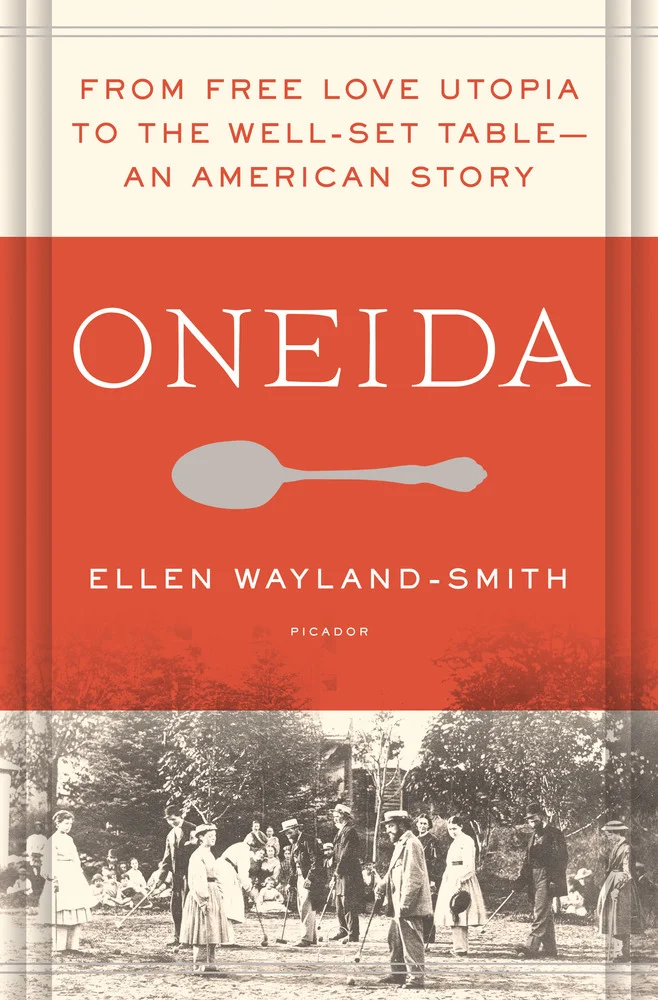

/Oneida: From Free Love Utopia to the Well-Set Table—An American Story by

Ellen Wayland-Smith

Picador 320 pp

By Ann Fabian

It’s not always easy to be introduced as the historian at the dinner table. Your hostess seats you next to a perfectly decent man who turns to you and says, “I have a theory about the Battle of Lake George.” I’m fine with theories, even at nice dinner parties. But the Battle of Lake George? Really? There was a battle? With ships and theories?

Quick to change the subject, I ask him, “Where did you grow up?” Oneida, he says. I knew just enough about his New York town’s utopian days to lead us back to his grade-school field trips and to chat us through the first course. But now, after reading Ellen Wayland-Smith’s rich, tangled and well-told Oneida: From Free Love Utopia to the Well-Set Table—An American Story, I could get us all the way to dessert and then pretty deep into the racy talk at the after party.

You can find the outlines of the story of Oneida in any American history textbook. Oneida was one of several utopian communities that appeared in the northern United States in the 1830s and 1840s. As the so-called market revolution churned through farms and communities of the northeast, visionaries, like Oneida founder John Humphrey Noyes, gathered up followers looking for alternatives to the harsh terms of the capitalist world emerging around them.

Oneida was born in the spiritual hot house of the 1840s, but the community lasted on into the 1880s, and then in a new guise through the first half of the 20th century, as a corporate and industrial mainstay of the tableware business. Oneida Limited was enormously successful in the prosperous years that followed the Second World War, and it’s likely that at one time or another, most of us have held an Oneida-made fork. But as a corporate entity, Oneida Limited erased its unconventional origins and peddled its silverware to middle-class housewives.

It’s hard to imagine those conventional housewives from Oneida’s beginnings. Noyes propounded a brand of “Bible Communism” hatched amid the religious and social ferment of the 1830s. As Wayland-Smith writes, “At the height of his powers, Noyes would command a following of nearly three hundred souls who saw, in his vision of a golden age communitarian paradise, an attractive alternative to the stingy, competitive regime of private property and monogamy that held sway in the profane world outside their doors.”

Noyes’s quarrel with monogamy gives this story a particular punch. Noyes developed a strange mix of theology and biology that “placed sexual intercourse at the very heart of Christian community,” sex for pleasure and for procreation. Oneidans weren’t the only ones thinking about marriage in the middle years of the century, but Noyes and his followers channeled their sexual urges in peculiar ways, practicing what they called “Complex Marriage”—neither the anarchy of free love nor the narrow selfishness of traditional marriage—but multiple, sequential couplings approved by community elders.

Noyes presided over his community’s elaborate choreography of sexual pairings, taking any number of fine young women to his own bed and making sure his adherents avoided the “sticky love” that would have filled the community with jealous rivalries. He advocated for coitus interruptus—“Male Continence”—to cut down on unwanted pregnancies. But more striking was the community’s turn in the 1870s to eugenic breeding practices, or what Noyes called “stirpiculture.” In an unusual eugenic trial, Oneidans set out to “cross-breed to produce a new race of super-Perfectionists.”

Wayland-Smith knows that the eugenic story—with its ties to horrors of racism and genocide—casts a creepy light on the whole business of Oneida. Doubly so in her case, because Oneida is her own family’s story. We don't usually have to spend time imagining the sex lives of our ancestors (although I suppose we could try), but Wayland-Smith knows a lot about the particular mix of erotic pleasure and planned coupling that ultimately brought her into this world.

She sometimes lost me in the weeds of her grandparents—the great, the great great and the great, great, great. And all the crossbreeding cousins became something of a fornicating blur. And much as I appreciated Noyes’s dissent from the mainstream, the idea that Noyes (and chosen elders) fathered children with nieces (or closer kin), all in the interest of Noyes’s self-gratifying schemes seems sinister.

But as a writer, Wayland-Smith plays her personal cards artfully, letting us see how this unorthodox community registered its century-long encounter with American culture. We watch as the utopian community morphs in response to ideas and events and witness a history that moves through the generations down to Wayland-Smith herself.

Years ago, one of Wayland-Smith’s relatives tried to write an insider’s history of Oneida, but in 1947 Wayland-Smith’s straight-laced great-grandfather presided over the burning of the archive. With so much of the story already recorded in letters, diaries, Noyes’s pronouncements, and the community’s chipper newspapers, it’s hard to imagine what scandalous revelation might have set the censors off to their bonfire at the Oneida town dump.

Believe me, the expurgated record is plenty good enough to liven up any dinner table. If you have a sheepish companion, you can tell him that Oneida gives us a chance to think about religion and science, Bible communism and American capitalism. Or, if you’re brave, you can head off theories about the Battle of Lake George just by pointing to the forks and knives and letting him know you have a good, long story about sex and silverware.

Ann Fabian is an American historian. She is working on a book about herpetologist Mary Cynthia Dickerson.