Q&A: The Pioneering Female New Deal Lawyer Who Went from an Orphan's Home to the Supreme Court

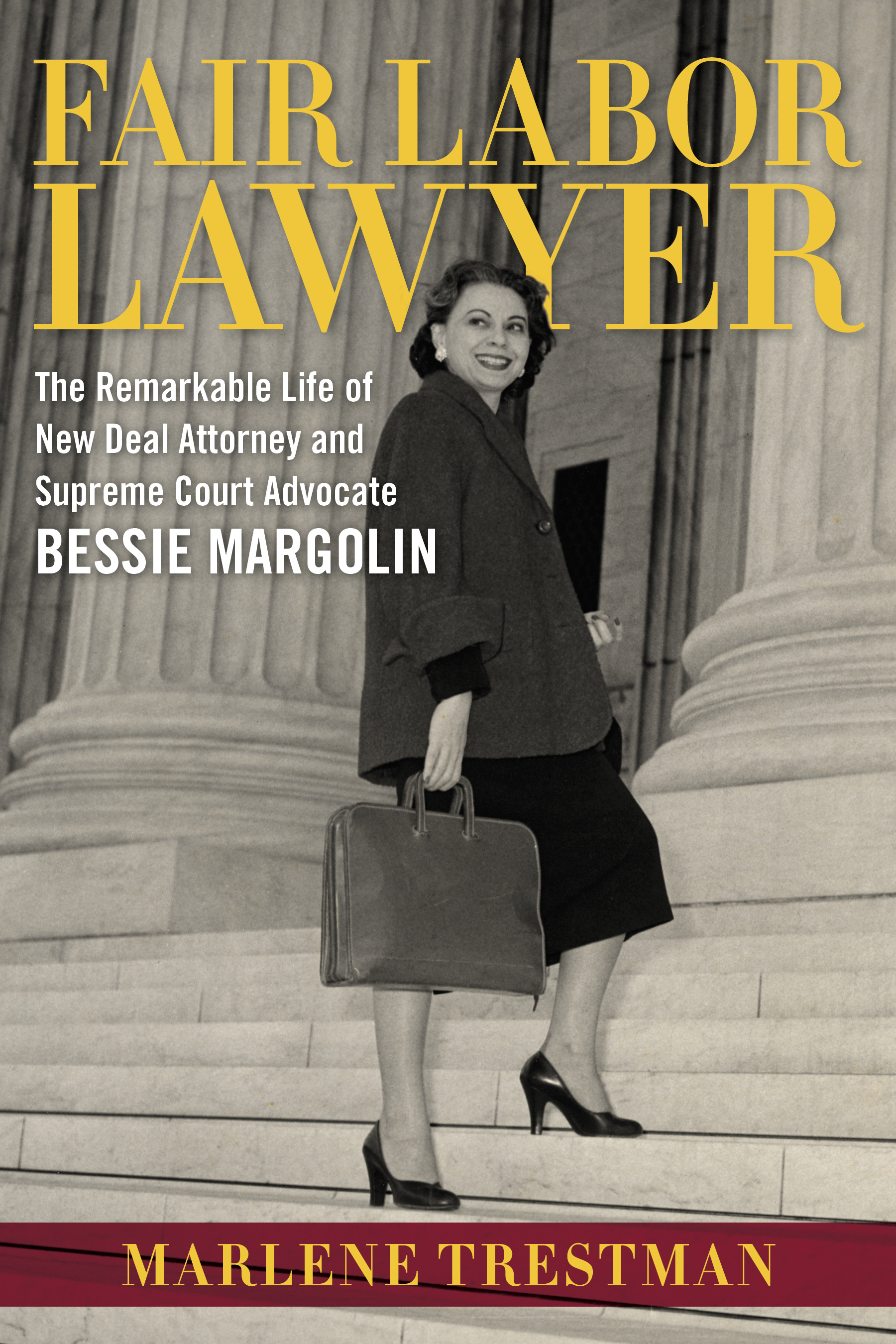

/Fair Labor Lawyer: The Remarkable Life of New Deal Attorney and Supreme Court Advocate Bessie Margolin, published last month by Louisiana State University Press, tells the story of a pathbreaking career in the law. The author, Marlene Trestman, answered questions from The National’s Leah Eskin.

Q: Bessie Margolin grew up in the Jewish Orphans’ Home in New Orleans. The two of you share some history. How did you meet her and how did she influence you?

A: Bessie Margolin and I are products of Southern Jewish benevolence, including life-changing educational opportunities. In 1903, a decade before Bessie was admitted, the trustees of the Jewish Orphans Home of New Orleans founded the Isidore Newman School to provide a rigorous secular education for its wards, but also admitted tuition-paying children, regardless of religion, from the broader community with whom the orphans learned side-by-side. The school quickly became what it remains today, a prestigious college prep school.

In 1967, two decades after the Home closed and Newman School became an independent entity, my parents died and I was placed in foster care under the supervision of the agency that succeeded the Home, today known as the Jewish Children’s Regional Service. At JCRS’s request, Newman admitted me on a full scholarship, honoring its founding mission to educate Jewish orphans.

Years later, when I left New Orleans to attend Goucher College, Newman’s guidance counselor — noting our common childhood experiences as wards of the Home and as Newman graduates — wrote a letter introducing me to Bessie Margolin, who had recently retired from her remarkable career as Associate Solicitor of the U.S. Department of Labor. Margolin graciously invited me for weekend visits to Washington, D.C., and our relationship continued through my years in college, law school and into the start of my own career as a government attorney.

Margolin, the first woman lawyer I ever met, was elegant, worldly, and kind. She provided helpful advice, captivating recollections of her career, important contacts in the legal community, and was a powerful role model for me. Little did she or I know that she was inspiring her future biographer.

Q: When Margolin began practicing law in 1930, you write, only 2 percent of American attorneys were female. Late in her career, in 1966, she helped found the National Organization for Women. Was Margolin always a feminist, or did she become one?

A: Your question goes to the heart of one of the most interesting facets of Margolin’s persona - her professed resistance to feminism — or at least her knee-jerk reaction to being called a “feminist.” Margolin, who pursued her legal career in a man’s world, sought only to be accepted as any highly qualified male attorney with exceptional academic credentials. Her original goals were personal; in fact, “intolerably dull” was the way Bessie described her 1933 summer job with the Inter-American Commission on Women cataloguing Latin American laws that discriminated against women. “I fear I’m not cut out to be this kind of feminist,” said Margolin, “I can’t scare up the least bit of enthusiasm over the legal equality between men and women in Latin America.”

But 35 years later, and only after she had spent several years as the nation’s top enforcer of the Equal Pay Act, which opened her eyes to the job discrimination suffered by many hard-working women, she told a reporter, “I’ve never been a feminist, but I’m becoming one.” In fact, she had become a zealous convert. Before she retired in 1972, Margolin oversaw the filing of 300 Equal Pay Act lawsuits in 40 states, and recovered millions of dollars for thousands of employees.

Despite her passion for wordsmithery, Margolin had resisted the label “feminist” throughout most of her career without ever defining the term to see that she had always been one.

Q: Margolin argued 24 times before the U.S. Supreme Court, winning 21 cases. She helped to enforce child-labor, minimum-wage, and overtime provisions of the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938. Is her handiwork intact – or threatened?

A: Although Congress has amended the Fair Labor Standards Act many times since it was in Margolin’s hands, the basic protections of the law and much of her foundational work — which Chief Justice Earl Warren described as developing the “flesh and sinews … around the bare bones” of the FLSA -- remain intact. For example, Margolin’s first argument (and victory) at the Supreme Court in 1945 (Phillips v. Walling), established the enduring principle that the FLSA is a humanitarian statute and its exemptions must be narrowly construed.

Bessie’s 1955 victory in Mitchell v. Joyce Agency, which required a comprehensive analysis of job circumstances to determine when workers are employees (as opposed to independent contractors) entitled to the Act’s protections, is still good law. Other examples of Bessie’s enduring work are the Supreme Court’s rulings that the FLSA requires compensation for any activities that are “integral and indispensable” to the principal job, such as showering and changing clothes to protect battery plant workers from toxic chemicals (Steiner v. Mitchell), and knife sharpening by meat packers (Mitchell v. King Packing Co). This principle was most recently cited by the Supreme Court in a 2014 case involving security screenings by workers at Amazon warehouses and earlier this month in a case involving the time spent donning, doffing, and sanitizing protective clothing by Tyson Food workers.

In her Equal Pay Act work, the most important precedent Margolin established through her appellate advocacy was in Shultz v. Wheaton Glass, a Third Circuit decision that the Supreme Court declined to review: work need be only substantially similar, and not identical, to warrant equal pay under the Act.

Q: Margolin assisted in the war crimes trials at Nuremberg. How did that experience shape her outlook?

A: Within the first two weeks of her 6-month tour of duty in Nuremberg, Margolin experienced a “revelation” about the gravity of the Nazi atrocities, which far exceeded any abuse or disregard for humanity she had witnesses in her child- labor cases. As the first American-born daughter of Russian Jewish immigrants, Margolin could no longer accept how any American could remain an isolationist, and resolved that “any little weight I may carry should be thrown in the direction of increasing the number of Nazis to be prosecuted for murder.”

By drafting the rules that established the American Military Tribunals, she helped mete out justice to more than 200 accused Nazis and sympathizers, including the doctors, judges and industrialists. Margolin and the close circle of friends she affectionately called her “old Nuernbergers,” had shared a role in shaping human destiny, a rewarding experience they sought to recapture in their careers.

Q: Okay, a little armchair psychology: Why did Margolin end up in so many clandestine relationships?

A: From Margolin’s pragmatic perspective, the married men with whom she worked offered the best combination of attributes for romantic partners: they were were brilliant lawyers with prestigious academic pedigrees; they shared her passion for using government to advance social justice; they appreciated her intellect; and were least likely to interfere with her independence or her career.

Margolin didn’t fully appreciate the importance of keeping her romances with married men “clandestine” until later in life. By all accounts, she did little to hide her passionate relationship with her Tennessee Valley Authority boss who was later the chair of the Federal Communications Commission — a relationship that was charitably described by many who knew them as “a widespread secret."

Q: Margolin was very private – you had to work with the limited papers she left behind. If you two could sit down now, what would you ask her?

A: So many things! Among the long list of very specific questions I would ask her are whether (and how much) she knew about the Congressional and FBI investigations into her private life, whether she supported the Equal Rights Amendment, and what did she least like about growing up in the Jewish Orphans’ Home. But above all, and perhaps this is common to all biographers, I’d like to ask Bessie Margolin whether she thinks I did justice in telling her remarkable story.

Leah Eskin is the author of Slices of Life: A Food Writer Cooks Through Many a Conundrum.