Q&A: Revelation, Jonah, Song of Songs, and More: Great Writers Reflect on the Bible

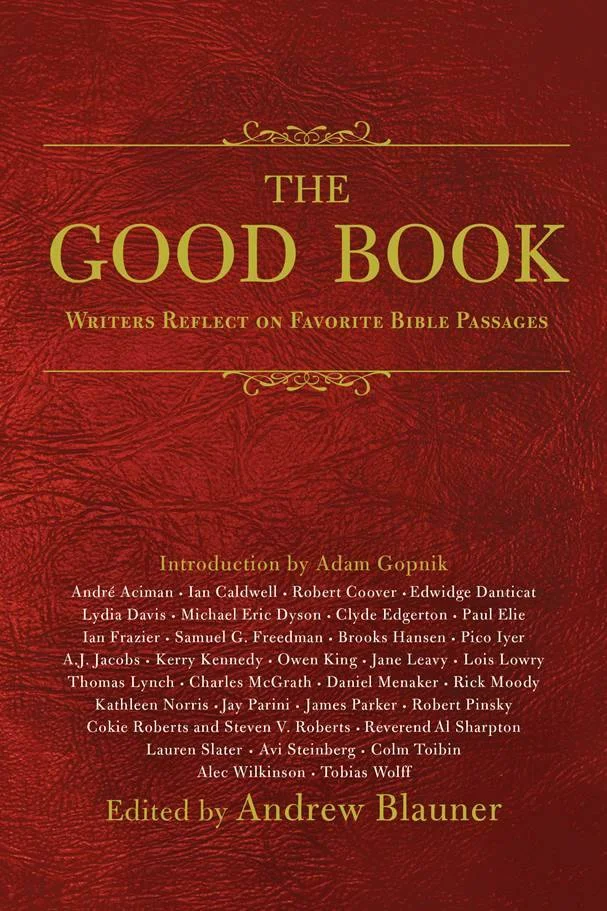

/In the new anthology The Good Book: Writers Reflect on Favorite Bible Passages, leading authors like Rick Moody, Andre Aciman, and Robert Pinsky do just what the book’s subtitle says. The introduction is by New Yorker writer Adam Gopnik, who argues that even in this largely secular age, the Bible still has a strong appeal for a simple reason: ultimately it is a book about people. In their essays, indeed, the contributors focus on the Bible’s rich assortment of characters and their very human problems.

The Good Book, published by Simon & Schuster, is the fifth anthology edited by Andrew Blauner.

Q: A lot of people wonder where anthologies come from. How did you come up with the idea to have writers reflect on their favorite Biblical passages?

A: Around the time I took Religion in the 7th Grade at Collegiate School there was a school production of Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat, and I saw Godspell. Years before that, I first saw A Charlie Brown Christmas, the most meaningful part of which, for many, is Linus reciting a passage from Luke.

But it wasn’t until years later that something sparked. On the one hand, the catalytic event was a Harold Bloom piece in New York Review of Books, entitled, I think, literally, “My Favorite Book in the Bible.”

I liked the piece and, instantly, loved the idea that NYRB was going to be publishing a series of pieces on the subject, inviting different people to write essays. When I learned they had no such plan, I thought, maybe this should be a book.

Then, some other things kicked in. More and more, I was becoming aware of references, allusion to the Bible, almost everywhere I looked—and even places I was not looking.

And often in places and from people who were not what we think of as “religious.” So much from the language to the lessons, the stories and sensibilities of the Bible were, it seemed, part of secular, quotidian life.

Who among us, irrespective of background, has not thought of, and invoked: an eye for an eye, the golden rule, am I my brother’s keeper?, the good Samaritan, turn the other cheek, the prodigal son, the patience of Job, the wisdom of Solomon, and on and on.

By the way, it was, I thought, telling that a study showed that in the days and weeks immediately following September 11, 2001, the number of people buying and reading the Bible spiked up, across virtually all demographics.

Q: Was it an idea publishers saw the value of right away?

A: Yes. Very much so. Happily, surprisingly so.

Q: How did you go about selecting the writers? What were the main qualities you were looking for?

A: Oh, that’s often a fun, fascinating, and/or frustrating part of the process. I wanted to select, er, invite people I thought would have something interesting, resonant, new to say about this, a very old subject. Great essayists, seminal thinkers, artful storytellers, mindful of not having it be a homogenous group, and making it more of a—what?—mosaic. “Anthology,” I think, comes from the Greek word for “bouquet” – a collection of flowers.

As some were very quick to point out, the book is not the kind of bouquet to its subject that some of my other collections have been. Most acknowledge that the Bible was the first book, the first printed book, that is. And by consensus it was definitionally an anthology, itself, written some speculate, by some 40 “contributors.” The Bible has 66 “books,” and is approximately 800,000 words, while The Good Book has 33 contributors and is approximately 80,000 words.

Q: Did you let them choose their own Bible passages, or did you do any matching of authors and subjects?

A: I had hunches, suggestions for some, but, at the outset, and in the end, I asked them all to choose their own. A couple were flummoxed, along the way, when, say, he or she decided late in the process, to sign on, that a passage about which he or she wanted to write was taken. And while I did not rule out, unconditionally, the possibility of having two people write about the same passage, I wanted to try to avoid duplication, unless there was a compelling case not to.

Q: Pull back the curtain a bit and tell us what it is like to edit a book like this. How much editing did you have to do of these essays?

A: Oh, that. That’s an easy one to answer. And I can liken it to being the coach/manager in an All-Star game, whose task it is not to get in the way, not try to do too much. Sometimes the hardest thing to do is to do nothing.

If you choose well, when it comes to the writers, then there is often not a lot of editing to be done. The surprising thing to some may be, naturally, that it’s some of the more/most accomplished/successful writers who most crave the editing/revising/collaborative process. So much, though, flows from the initial idea.

No two anthologists, I’m sure, approach the projects and processes the same way, but there is always a lot to do, beyond what’s traditionally thought of as editing, and “editor,” in many instances, can really be a misnomer. What would be better, I don’t know, but some have suggested it’s more like being a producer or curator or some cocktail of those things, coupled with, hmmmm, what else is it that I hear, oh, therapist, but I don’t experience that part of it. Which is not to say that you’re not dealing with psyches, psychologies, personality, pride… You are.

Q: How many writers missed their deadlines? Did you commission any essays that didn't work out?

A: How many writers missed their deadlines? What an endearing question. At the risk of parsing things that may code Clintonian, it depends on what your definition of “deadlines” is, or even what “missed” means. But I can only say, broadly, that many missed many deadlines.

And did I commission any essays that didn't work out? YES.

Q: There are a lot of remarkable essays in the book by some very prominent writers – Daniel Menaker on Jonah, Pico Iyer on Song of Songs, Jay Perini on the Sermon on the Mount. It wouldn’t be fair to ask which is your favorite, but are there any essays that particularly spoke to you?

A: You mention two whom I consider friends, there, in Dan and Pico. And I have long had nothing but great admiration for Jay. You’re thoughtful not to ask me to name a favorite. And when put on the spot, in the past, with the other books, I think that, perhaps, the only times I ever singled anyone out were, in a previous anthology I did, Coach: 1) Roger Angell, figuring nobody could/should/would take exception, feel bruised by that, all things considered, and if they did, well, so be it; and 2) David Duchovny, the actor -- and screenwriter, and director, and novelist -- an old school friend, writing about the coach we shared, Larry Byrnes, at the aforementioned Collegiate School.

But in the Good Book …. in terms of which essays particularly spoke to me I’d be remiss if I did not mention how much I personally love Edwidge Danticat’s chapter, “A Voice from Heaven,” on Revelation 14:13.

I think it fair, too, to say that what spoke to me first and on its own, special level, was Adam’s Introduction. And if you want a taste, a feel for why, well, I’d venture to say that there is no hour better spent listening to anything more than this conversation between Adam and Krista Tippett, on “On Being,” a conversation that was inspired by Adam’s table-setting piece in the Good Book.