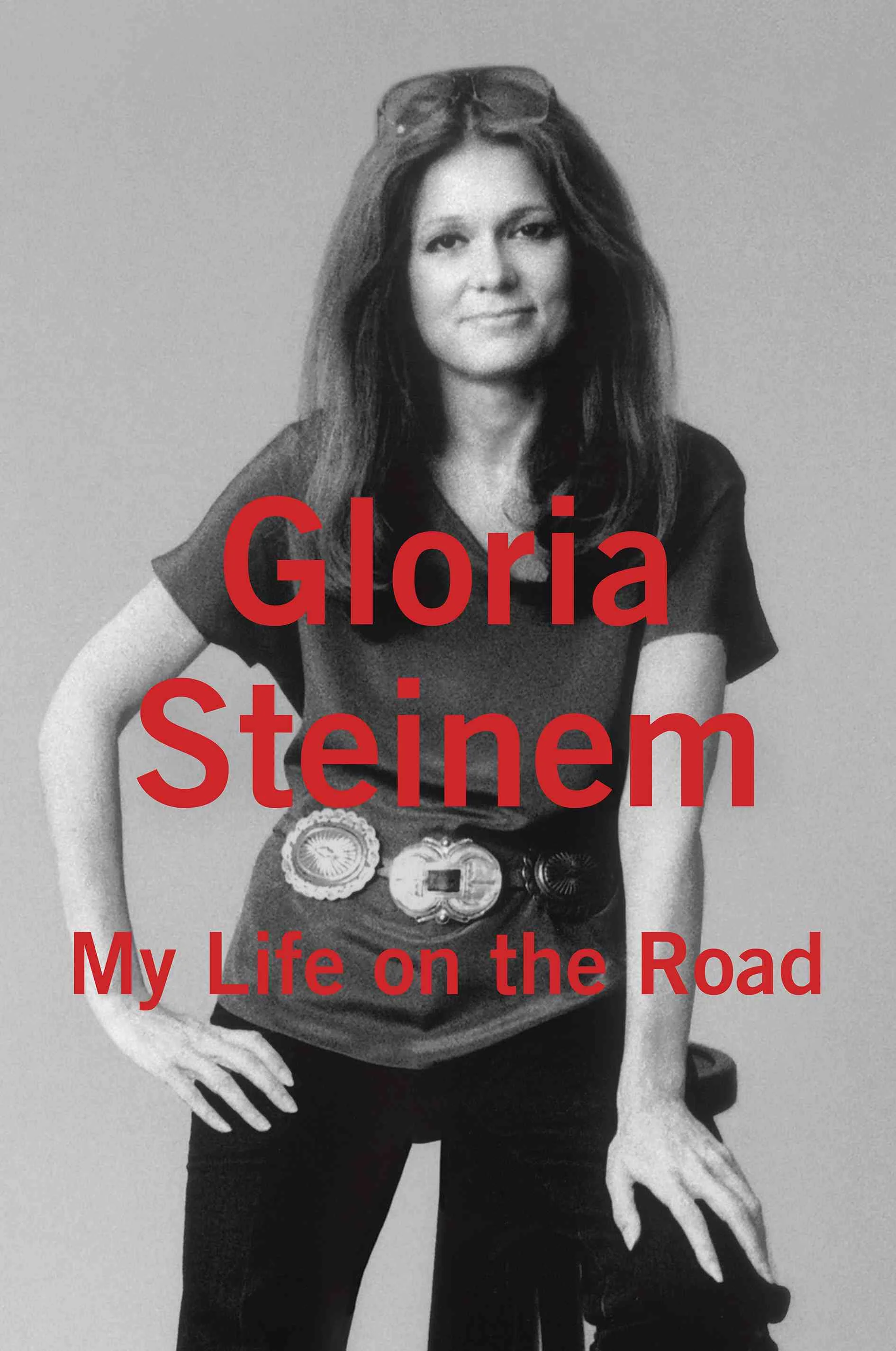

Review: A Feminist Icon Takes Us On a Sometimes Too-Fast-Moving Adventure

/My Life on the Road

By Gloria Steinem

Random House 304 pp. $28

By Carol Owens

Gloria Steinem is a real person. That may be stating the completely obvious, but it also accurately sums up the dawning realization a reader feels while making her way through Steinem’s lyrical, fascinating, and ultimately frustrating memoir, My Life on the Road. As key a figure as Gloria has been in the Second Wave of feminism – and there is no argument about the centrality or longevity of her leadership – she herself as a person has remained in the shadows.

Certainly, Steinem is recognizable, and in fact, easily described: her physicality, her distinct manner of dress and speech, the aviator glasses and center-parted long hair unchanged over the years. She is readily and easily associated with her championing of the core political causes meant to achieve women’s equality and basic civil rights: the Equal Rights Amendment, the National Organization of Women, and Ms. magazine. At 81 years old, she has been in the public eye for nearing six decades.

And yet, despite being at the red-hot center of one of the most important social movements of the last century, Steinem has somehow managed to remain a singular person, her own person, never defined by her relationships to others in the way most women find themselves: daughter, sister, lover, wife, mother, aunt. She has always just been Gloria Steinem.

Perhaps this is why the first third of My Life on the Road is such a pleasant surprise, shattering whatever preconceptions of normalcy about Steinem’s early years may have existed. Instead of reading the expected story of the hardscrabble life of a Depression-era childhood, there is Gloria’s family living happily in Toledo, Ohio -- mother, sister, and most surprising, father Leo.

Gloria’s father’s outsize figure is the one that looms largest both physically and in spirit. Leo, the son of German and Polish Jewish immigrants, is a restless wanderer by nature. As soon as the summer begins to wane, not too long after the camp where he runs an entertainment pavilion has begun to empty out, Leo packs his wife and daughters into the car and heads out for the open road.

This is, of course, just when the school year should be beginning, but there is no mention of Steinem’s early, formal education. Instead, she describes her life as a passenger in the family car, headed to one warm-weather destination or another, as she reads whatever books she wants and is indulged in her love of horses at various stops along the way.

To support the family, Leo, Gloria, and her sister cull treasures from roadside antique stores and yard sales. Leo, it is clear, has taught them how to spot quality in precious metals and jewels, a skill Gloria’s never-named sister utilizes in her adult life when she becomes a jewelry buyer in a department store. The Steinems prowl the back roads, snapping up small treasures from unsuspecting or desperate householders and loading them up in their car. Steinem says her father, a man of well over three hundred pounds, was noted for his propensity for carrying loose, perfect jewels wrapped in tissue paper in his pockets, small treasures that he first admired and hoarded before selling to feed the family and fuel the car.

Steinem never refers to her father as a grifter, and it is clear she has only fond memories for this start to her life on the road. Still, there is so very much left unsaid in her often-poetic descriptions of her early years. One throwaway sentence gives a small hint, when she mentions the resonance she felt on first seeing the father-daughter pairing in the movie “Paper Moon.” There is much to be said there, but she writes nothing further about it.

This is Steinem’s style as a memoirist: giving the reader a quick glance at a fascinating part of her life, such as her peripatetic childhood, and then closing the door before the reader can look too long. So it is with Steinem’s mother, who remains a cipher, a literate woman whose own journalistic career was cut short by mental illness and by the gender-based limitations of her time. Once again, the reader is left saying to herself: tell me more.

After she graduates from Smith College and begins her own career as a journalist, Steinem acknowledges that she is in part living the life her mother never could, even as the aggregation of her traveling tales makes clear that she is very much her father’s daughter. Always on the go, Steinem is a hoarder of valuables of a different kind – connections that she makes with people, often other women, along her path.

Like many great travelers, Steinem manages to cover a lot of ground in part by rarely looking back. She is not one for regrets – the only one she expresses in this memoir is that she was unable to get to her father’s side before he died. Her mother and her unnamed sister then disappear from her narrative, never to be mentioned again.

It is not only family that Steinem holds at arm’s length. Even in the most heartfelt of the later sections of the book, when she writes about the long, important friendship she had with Wilma Mankiller, the distance is notable. There is no doubt about the love and kinship – the sisterhood – Steinem felt with Mankiller. And yet the grief that she feels about the loss of that relationship to death is muted, hidden between the lines.

In her adult years, Steinem’s life intersected with many of the biggest literati and glitterati of the 20th and early 21st centuries, but few of them appear in the pages of My Life on the Road. It is to her credit that she is not a namedropper, as so many memoirists are, but again the reader is likely to be left wanting a bit more. The names Steinem does share are almost all female, as in the long section, “Talking Circles,” which reads like a compendium of famous names from the Civil Rights Movement and the Women’s Movement.

Recalling those historic times, Steinem writes a good deal about how she and the other participants communicated. She discusses her training in listening and facilitating change through achieving consensus, lessons she ascribes to the time she spent in India, her work with female leaders of the American Civil Rights movement, and her later associations with indigenous people both at home and internationally.

Steinem is much taken with the concept of the “talking circle,” a traditional Native American way of working through problems. It is a structure that allows people to give a little, get a little back, create understanding – and then move on. It is not hard to believe some of the attraction of this episodic mode of communication, for her, is its similarity to her earliest days on the road.

In the end, it always seems to come back to moving on. Steinem would no doubt be a fascinating person to sit next to on a plane or train, or in the backseat of a car rolling down the highway. Her stories would certainly make the miles fly by. If only there were more to them. If only we could really get to the heart of things before she bid a polite goodbye and moved on to the next adventure.

Carol Owens is a Boston-based writer.