Q&A: Sam Freedman on The New York Times Reporter Who Changed AIDS Journalism Before Dying of AIDS

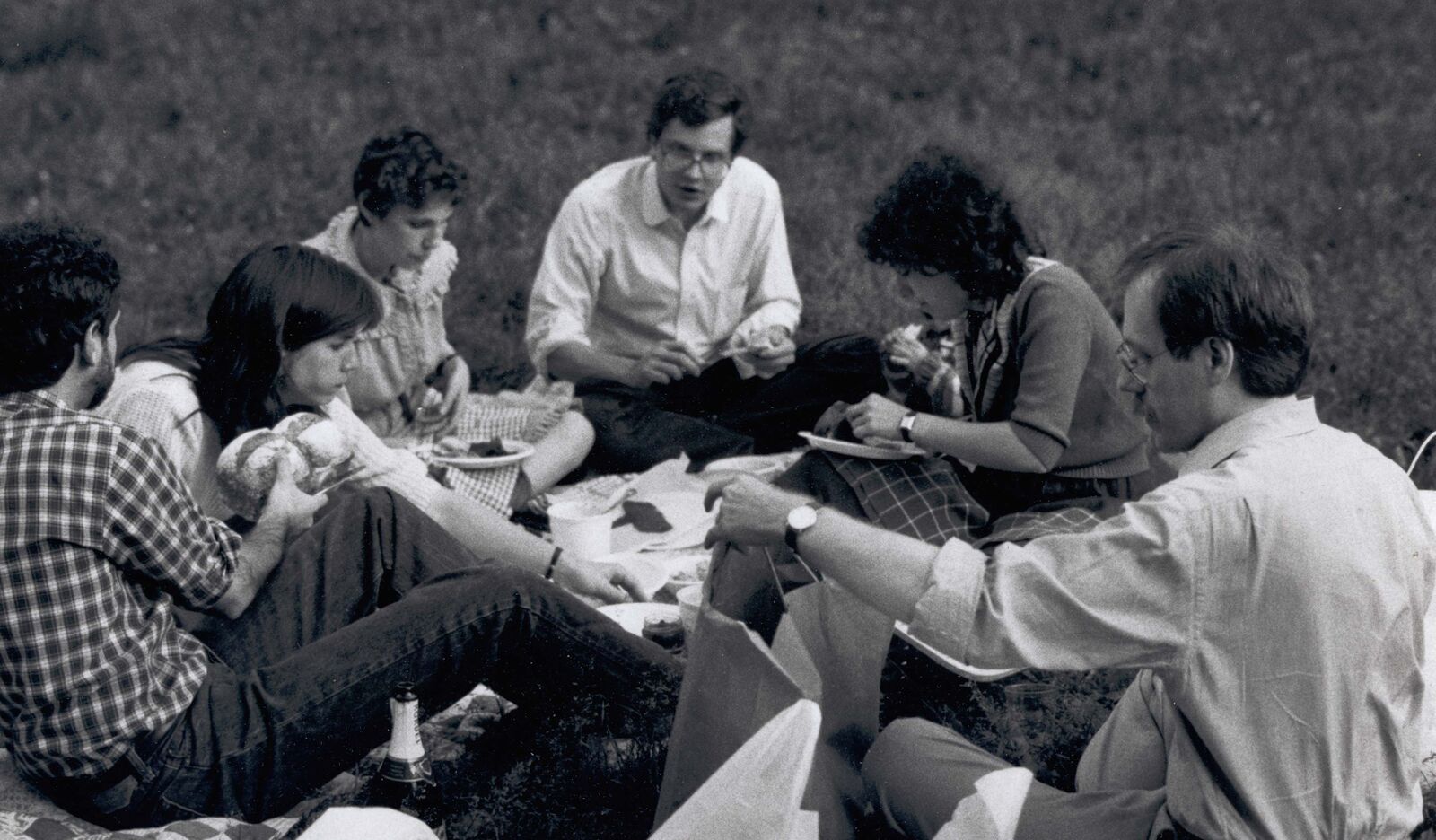

/Samuel G. Freedman (left), Arthur Sulzberger, Jr (center), Jeff Schmalz (right), and other New York Times journalists

Jeff Schmalz, who worked at the New York Times for more than 20 years before dying of AIDS, was a pioneer as a gay journalist at a time when the profession was often hostile, and one of the most influential reporters to cover the AIDS crisis.

Samuel G. Freedman, a Columbia Journalism School professor and himself a New York Times veteran, has written Dying Words: The AIDS Reporting of Jeff Schmalz and How It Transformed the New York Times (available on Amazon), accompanied by an audio documentary by radio producer Kerry Donahue. The project was funded through a Kickstarter campaign.

We spoke with Freedman about Dying Words, and about Jeff Schmalz – who was just 39 at the time of his death – and his legacy.

Q: Tell us a little about Jeffrey Schmalz. How did you get to know him, and what was he like?

A. I met Jeff in my first day or two on the Times in December 1981. In fact, it was this exact week 34 years ago when I started as a reporter on metro. I was based in the Connecticut bureau and Jeff's official position was regional editor, in charge of all suburban coverage, so he was my boss. He actually ran virtually the whole metro section because he was so talented. I was stunned that someone in a position of such authority was so young -- just 28, two years older than me.

Jeff was focused, on-point, witty, sometimes sardonic. He was also a superb newsroom rabbi for me. He taught me Times style and standards, since I was making a big leap from working in the suburbs of Chicago. He was a great advocate when I did a story well. I still remember the phone ringing in our bureau and his greeting me, "hi, Scoop!" but if I fell short, for instance if a story wasn't balanced, he'd very icily say, "when I read this story, I know exactly what Sam Freedman thinks."

Q: What was the Times newsroom like in the early 1980s – and what was it like for gay people?

A: Although Jeff was out to me and to other young reporters and editors he felt would be sympathetic, he was closeted to the editors who controlled his career. And that was typical. Abe Rosenthal, the executive editor, was a brilliant man in many ways, but he was insensitive or outright hostile to gays and lesbians and to LGBQ causes.

The gays and lesbians in the newsroom felt that chill. I knew some who made paper marriages so as to appear straight. I knew others who were demoted once their sexual orientation became known. And in doing the book and documentary, I’ve now come to know far more than I knew at the time.

Q: When was Jeff Schmalz diagnosed with AIDS? What happened next? Did it force him to disclose both his illness and sexuality?

A: AIDS outed Jeff. He had a grand mal seizure in the newsroom in late 1990, when he was deputy national editor, and about two months later, it was confirmed that he had full-blown AIDS.

By 1990, Abe Rosenthal had been pushed into retirement and his successor, Max Frankel, was very inclusive on LGBT issues. The same was true for Arthur Sulzberger, Jr., who was in the process of supplanting his father as publisher.

But even in this more tolerant climate, Jeff retained the old fear that coming out might hurt his career. So only with the AIDS diagnosis did he tell Max and other top editors he was gay, as well as that he had AIDS.

Q: After this disclosure, how was Schmalz treated?

A: Jeff was one of the most respected people in the newsroom, a quintessential Times man. So he was completely embraced and supported. Max Frankel was literally holding Jeff's hand as they waited for the ambulance on the day Jeff had his seizure.

And when Jeff returned to the newsroom seven months later, top editors looked for a way to best use his talent. Initially, it was in covering the 1992 presidential race, but Jeff very quickly realized that he felt a mission to cover AIDS. The Times had never had an AIDS beat before, and it covered AIDS primarily as a medical story or a political story. Jeff made it a human story.

Q: How did Jeff Schmalz start covering the AIDS crisis?

A: Jeff started doing a couple of stories on the gay constituency in the 1992 campaign and got so much positive feedback from LGBT readers that he went more fully into the AIDS issue in the presidential race. Remember that this is 1992, when both parties have HIV-positive people addressing their convention. And once the election ended, Jeff did nothing but AIDS coverage for that would turn out to be the last year of his life.

Q: Can you explain what coverage was like before Jeff was on the beat? How did he change the coverage, and did any particular stories about AIDS stand out?

A: As I said before, AIDS before Jeff was treated as a medical story. And, even at that, the Times was reviled by groups like ACT UP for having been so late to the AIDS story -- a criticism that is valid.

What Jeff brought to the coverage was a deep compassion and a terrible firsthand knowledge. And he put them to use in a series of memorable profiles of people with HIV or AIDS -- from Magic Johnson to Harold Brodkey, from Mary FIsher to Randy Shilts. Jeff wrote with incredible tenderness, but he was also unflinching in his questioning. And in two extraordinary first-person articles, Jeff was every bit as piercing in writing about himself.

Q: What is his legacy – for the Times, and more broadly?

A. Jeff set the standard for AIDS coverage in the mainstream media. After his example, any major news organization realized it needed a full-time AIDS reporter. Jeff also captured AIDS as it was moving from a disease of largely gay men to a disease afflicting all corners of society.

Internally at the Times, Jeff sensitized the paper not only to AIDS but to the lives of LGBT people inside and outside its newsroom. And his several first-person articles really advanced the frontier of what we might call literary journalism at the Times. All of these effects were felt in the news industry as a whole not only because of Jeff’s talents but because of the Times' influence.

Q: How did you come to decide to undertake this book, and why do it as a book with audio?

A: I was talking to a few friends in 2011, right after New York State approved marriage equality, and marveling at how the formerly unsympathetic New York Times had become the champion of LGBT rights. And that led me to talking about Jeff.

I was stunned when one of my friends, a longtime journalist turned TV writer, didn't even know who Jeff was. I realized right then that Jeff's work and legacy were being forgotten. And the way the project made itself felt to me was as voices talking -- Jeff's voice and the voices of those who worked with him and the voices of those he wrote about.

At that point, I partnered with an exceptional radio producer, Kerry Donahue, who knew what I did not know: how to produce a radio documentary. We did all the interviews and other research together over 18 months.

And as I began to think about a book, it was my editor-publisher, Tim Harper at CUNY Journalism Press, who argued against just doing an anthology of Jeff's work. At Tim's prodding, I came up with the concept of an oral history book that included excerpts from Jeff's work as well as other "found objects" -- diary entries, letters, passages from interviews. And I bracketed all of that material with a foreword and afterword that I wrote.

Q: How were you changed by Jeff, and what impact did this project have on you?

A: Jeff was the first person to unashamedly come out as gay to me. He made being gay normal to me. He talked about flirting and dating and sleeping with people -- exactly as a straight friend might have done. And I owe a lot of my career to his role as my rabbi.

Then he was the first person I knew well to die of AIDS, the person at whose bedside I sat in his final days. So he made the AIDS epidemic painfully real to me. And he left me with a sense of moral obligation that I sought to fulfill by doing this book and documentary.

To download the radio doc: https://soundcloud.com/dying-words-project