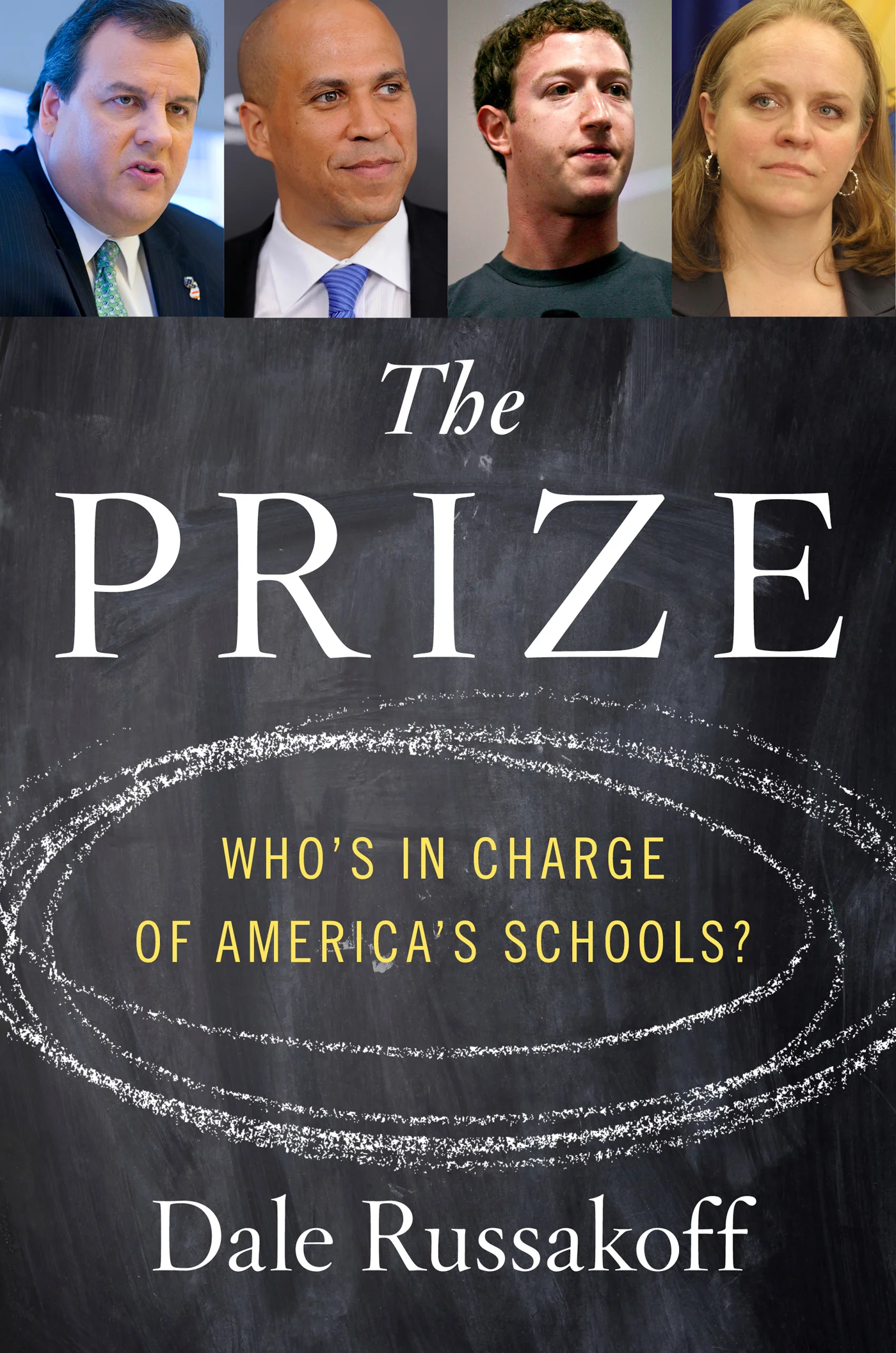

Review: How Mark Zuckerberg, Chris Christie, and Cory Booker Flunked School Reform

/By Jim Swearingen

The Prize: Who's In Charge of America's Schools

By Dale Russakoff

Houghton Mifflin Harcourt $27.00

Chris Christie, the Republican governor of New Jersey, and Cory Booker, the Democratic mayor of Newark, were driving through Newark’s most blighted neighborhoods in a limousine on a cold December night in 2009 plotting school reform. It was an odd pairing, but it soon got odder – when they enlisted Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg on a secretive, high-stakes plan to overhaul the Newark schools.

It was a dream team that appeared to have everything – a conservative hero, a liberal darling, $100 million of Zuckerberg’s fortune – and a bold vision for remaking American urban education. What could possibly go wrong? What could go wrong – what did go wrong – is the subject of Washington Post reporter Dale Russakoff’s smart and compelling The Prize: Who’s In Charge of America’s Schools.

There are few devices that make for better political theater than one-time opponents teaming up to combat a common enemy. And there are few causes more captivating than saving children in peril. This would have been an amazing story of bipartisan, public-private cooperation if Christie, Booker, and Zuckerberg had succeeded in taming an entrenched educational bureaucracy that cheated poor kids for half a century – and designed a model for reform nationally.

Instead, The Prize is something more sobering, but no less valuable: a story of how good intentions went awry. As Russakoff documents, an opportunity for political collaboration on a vital issue was lost when politicians ignored stakeholder input, the intrinsic motivations of inner city teachers, and the larger problem of urban poverty while allowing their own political ambitions to distract them from their ultimate goal.

The story begins with Booker and Christie forming an unlikely alliance to save children atrophying in urban schools. Their plan was bold: close failing schools, add charter schools, dismantle teacher tenure, and establish a pay-for-performance system that rewarded teachers and principals not for longevity, but for how their students performed on standardized tests.

The plan was also top-down: when Booker presented Christie with a written proposal it made no pretense of transparency, negotiation with stakeholders, political compromise, or grassroots participation. Rather, it would force reform by using unprecedented donor funding to saturate Newark with charter schools and unilaterally reconfigure teacher compensation.

Booker designed the enterprise to bypass the lumbering dinosaur of Newark Public Schools and create new schools outside the system, hand picking principals and teachers, paying them for high performance, and retaining only those deemed effective. The payback, Booker hoped, would be Christie handing state control of the Newark schools and their $1 billion budget over to the mayor while simultaneously improving local children’s education.

Booker proved himself a charismatic political fundraiser. Promising a revolutionary overhaul of urban education, he roped in Zuckerberg and his millions. This was not the cold-blooded techie of The Social Network. This Zuckerberg went into the venture as an effective corporate manager trying to learn how to be an effective philanthropist.

Zuckerberg was looking for a way to fix public schools generally and dismantle teacher tenure specifically. That would require removing the traditional protection of “First In, Last Out,” which calls for teachers to be dismissed in seniority order when budgets are cut, rather than starting with the least effective ones.

After numerous secret conversations, Booker presented Zuckerberg with a five-year plan, largely crafted by consultants, to use Newark as the launching pad for a national public education reform strategy that included data-driven accountability, improved teacher recruitment and training, and almost as an afterthought, a public relations arm to generate support. Zuckerberg responded with a $100 million matching grant for teachers’ pay-for-performance. Booker was tasked with finding the other $100 million.

No one was tasked with informing Newark that its school system was about to be overhauled by a pair of politicians with a think-tank plan, backed by a Silicon Valley fortune. Newark parents found out what lay in store for their children when Booker, Christie, and Zuckerberg appeared on Oprah to take a victory lap.

After this television unveiling, Booker launched a PR campaign to win citizen support. In public forums and door knocking campaigns, Newark residents were invited to share their ideas and voice their concerns. But nothing they said mattered. Unbeknownst to them, the fix was already in.

The strategic dismantling of the local school system had already been launched in closed-door meetings with highly paid consultants and out-of-state donors. The plan entailed closing neighborhood schools, opening charter schools, and revamping teacher tenure in exchange for donor support.

All of the things that predictably would go wrong did. In an economically depressed city where the public schools were the largest employer, threatening the educational bureaucracy caused a fierce backlash. Newark residents knew their schools needed help, but they were not excited about having a peevish Republican governor, a narcissistic Democratic mayor, and a West Coast tech baron using their city as an educational laboratory.

When the community saw what was happening, a political insurgency arose. Not surprisingly, the great reform plans unraveled as various stakeholders asserted themselves. In the end, most of Zuckerberg’s millions went to retroactive compensation for the old cadre of teachers, not incentivizing future teaching excellence. The issue of returning control of Newark's schools to the mayor’s office was never resolved. The dismantling of “First In, Last Out” never materialized.

Russakoff understands something important the reform triumvirate did not: how much of educational success occurs, painstakingly, in classrooms. The plan to fix the Newark schools lacked any classroom-level specifics. Innovative literacy programs, reading tutors, and media centers were dismissed by Booker’s highly paid reform apparatchiks as old hat.

Underneath the larger reality that Newark schools were not teaching well, Russakoff documents the tireless, self-sacrificing efforts of some principals and teachers who researched innovative new means of teaching students to read, to calculate, and to respect themselves. Their willingness to create an individualized social safety net for the most vulnerable children went unnoticed and unheralded by the reformers.

Long before pay-for-performance was discussed in those secret meetings, bright and dedicated Newark educators committed themselves to the demands of teaching poor, urban children without receiving traditional corporate rewards. One wonders what sort of reform plan Booker might have developed had he invited these selfless professionals to be part of the conversation.

Eventually, the reformers moved on. Booker proved to be easily sidetracked by new photo opportunities and his Twitter feed. By 2013 he had moved on to the Senate and dropped Newark school reform. Christie can, of course, be seen pulling up the rear at Republican presidential gatherings across the country.

Zuckerberg, who initially appeared to be another hapless do-gooder seduced by Booker’s charms, comes off best of all. He was the one principal who followed through on his promises – including his $100 million pledge. When he moved on, he and his wife tackled a more nuanced version of urban school reform in the San Francisco Bay area using the expensive education he acquired in Newark. Their latest venture addresses the physical, social, and emotional well-being of poor kids along with their formal schooling.

Zuckerberg’s epiphany – about the importance of attending to the whole child – is something the Newark plan needed from the start. In Russakoff’s telling, teachers, social workers, and principals all related the traumatizing effects of violent crime, drug culture, unemployment, sub-standard housing, poor nutrition, parental exhaustion, and rage on schoolchildren. Constantly gnawing at the edges of this story are the social costs of poverty – and its devastating impact on urban education.

The Prize is, as much as anything else, a morality play about what happens when plans are formulated for people instead of by people – and when the people doing the formulating ignore the single biggest element of the problem. It underscores that we cannot solve the failures of urban education without addressing inner city poverty.

That goal will require a long-term dedication of capital greater than Zuckerberg’s paltry $100 million. And it will require politicians to stick around long enough to do the hard work that is necessary. As Russakoff’s story sadly makes clear, there were no winners in Newark – and the prize is still up for grabs.

Jim Swearingen is an assistant high school principal, and a writer, in Minneapolis, Minnesota. The views expressed here are his own. Follow Jim on Twitter at @Jim_Swearingen