Essay: Patricia Highsmith's "The Price of Salt," The Lesbian Novel That's Now a Major Motion Picture

/The movie Carol, starring Cate Blanchette and Rooney Mara, opened in New York and Los Angeles last weekend. Carol, which has gotten rave reviews and is generating Oscar talk, is based on The Price of Salt, a novel by Patricia Highsmith.

By Erin G. Carlston

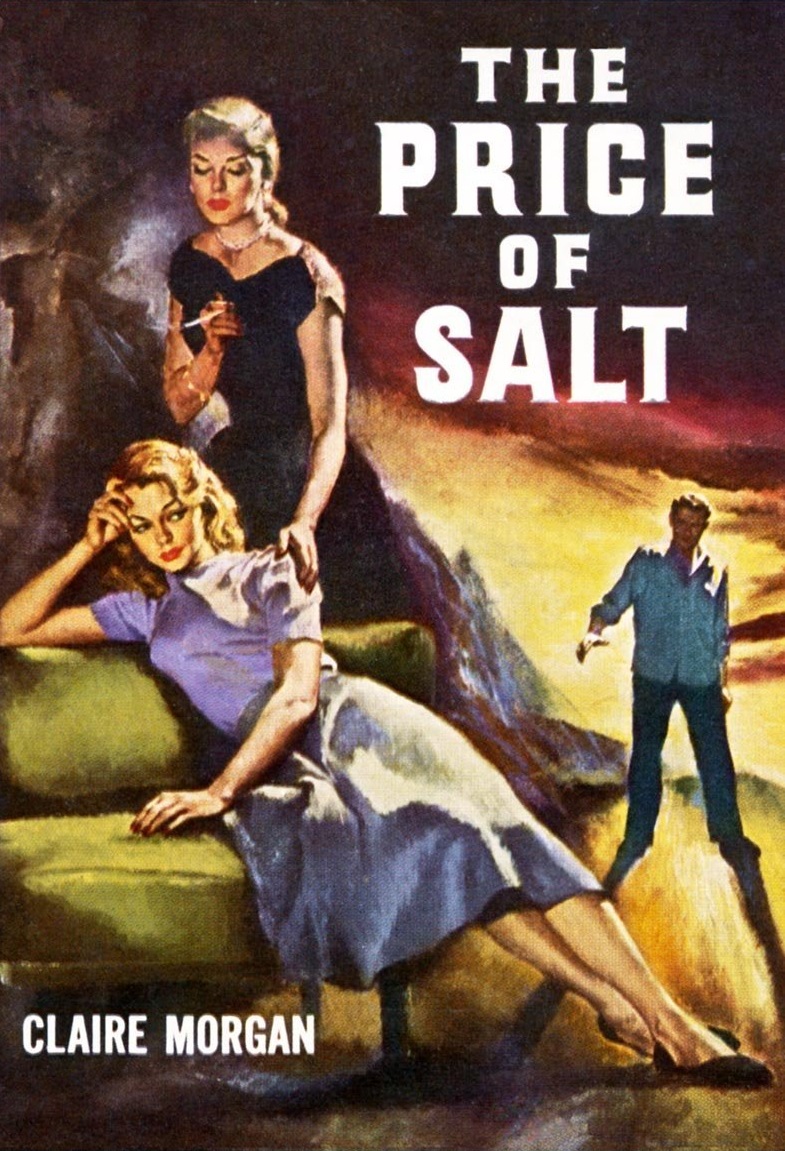

Right now I’m looking at three novels on my desk: The Price of Salt, by Claire Morgan, with a photo of a salt shaker on the cover; The Price of Salt, by Patricia Highsmith, with a blurry black-and-white photo of a young woman and the tagline “Now A Masterwork, the Novel That Inspired Nabokov’s Lolita” (about which more in a moment); and, on my Kindle, The Price of Salt: Or Carol, also by Patricia Highsmith.

These are all, of course, the same book, or versions of the same book, and if I wanted to spend the money I could add a bookshelf’s worth of other versions of this malleable text. In the multiple permutations of this novel we can trace the historical arc of American attitudes towards, and marketing of, lesbianism from the 1950s until today. Its fortunes have been, in a sense, the fortunes of queer Americans themselves.

The Price of Salt is the story of the love between Therese, a budding set designer who works in the toy department of a department store, and Carol, an elegant customer who comes into the store one day. When the book was first published, in 1952, Patricia Highsmith—a thirty-year-old writer who’d just had a major success with her novel Strangers on a Train—couldn’t take the risk of issuing a lesbian romance under her own name; in fact, the mostly-closeted Highsmith wouldn’t admit publicly that she was the novel’s author until she was in her 60s. After her real name made it onto the cover, the title was changed to Carol for the U.K. and Commonwealth editions, presumably because the original title was considered too cryptic—not that Carol tells us much more.

With its well-known author hiding behind a pseudonym and neither title giving much away, publishers have relied on the covers to sell the book. The cover of the original 1952 hardcover edition explains to the prospective reader that she holds in her hands “A Modern Novel of Two Women,” discreetly promising something sophisticated and psychological. It’s aimed at a reader who likes to think of herself as up-to-date, broad-minded.

The 1953 Bantam paperback edition has a garishly colored pulp cover and bears the tantalizing heading, “The Novel of a Love Society Forbids.” It targets buyers titillated by the racy cover art, while trying to hedge its bets by including a demure blurb from a New York Times review claiming that the novel “[handles] explosive material... with sincerity and good taste”— a recommendation that may actually have been off-putting to readers who were looking forward to the forbidden love bits, and to hell with good taste.

Over the next sixty years editions multiplied, attributed variously to Morgan or Highsmith, titled either The Price of Salt or Carol, with all kinds of covers and blurbs. Many of these later editions aim to appeal to an arty, highbrow crowd, as is suggested by my Norton edition’s bold claim that the novel “inspired Lolita”—which as far as I know is only a hypothesis that Terry Castle advanced speculatively in a 2003 New Republic article on Highsmith, not a fact.

My own notes for this article were taken from the 1986 Naiad Press edition. Naiad was the largest of the lesbian/feminist publishing firms that arose in the 1970s to print and distribute work that mainstream publishers and bookstores wouldn’t handle. While many of the readers of Highsmith’s work in the 1950s must have been lesbians and gay men, nobody was marketing books specifically to them until queers and feminists launched presses and bookstores that became lively sites of political and cultural activism. My cherished Naiad Price of Salt is a reminder of that valiant and vital effort to recover gay and lesbian histories, to bring a culture to light, and in doing so to fuel a movement that ended up changing the social and political landscape of the United States forever.

The latest entrant in this array of editions indicates just how dramatic that change has been. It’s the book labeled Carol (Movie Tie-In), released as part of the marketing campaign for the “major motion picture” announced on the new cover, which also features the exquisite faces of the film’s co-stars, Cate Blanchett and Rooney Mara. A book that began with an author who couldn’t acknowledge it as her own work, marketed in turn to the intelligentsia, thrill-seekers, and members of a minority sub-culture struggling for recognition, is now the basis of a “major motion picture,” starring two of the most celebrated actresses in the world and generating all kinds of awards-season buzz. The film is likely to garner multiple Oscar nominations, and it will probably make a lot of money, as will the novel. And millions of people around the world—in the parts of the world that allow such films to be shown—will watch a well-told, well-acted story of two women in love and be moved by it.

This is unquestionably progress, of a kind, and I have no quarrel with it, although I’m saddened that the queer and feminist presses and bookstores that helped keep The Price of Salt and novels like it in print have almost all closed. But it’s hardly an original observation that along the road to mainstream cultural acceptance, marriage equality, and general respectability, queers lost many of the community institutions and much of the oppositional energy that sustained us through so much devastation, for so long: a sign of either our success or our co-optation. But either way, there’s no doubt that life has gotten easier for many of us since 1952.

In charting the changes between then and now, though, there are two mistakes we could make, and I’m already anticipating that responses to the movie Carol will make them. The first is to imagine that things now are much better than they are. The second is to imagine that the 1950s were even worse than they were.

The first error is a fairly obvious one. Sure, today Highsmith’s beleaguered lovers Carol and Therese could make their road trip as a legally married couple (or could if Carol’s divorce from her husband, Harge, were finalized). But their reception in many small towns across the American West would probably be even chillier now, when the nature of their relationship would be recognized, than it would have been in the 1950s when two women could share a hotel bed without being thought more than chums. People still lose custody of their children because of their sexual orientation, if not quite so automatically as they would have in 1952. People still get fired or kicked out of their homes because they are, or are thought to be, gay. Queers still get killed—especially when they aren’t protected, as Carol and Therese are, by white skin, gender conformity, and class privilege. All this, we know.

What’s harder to see, given just how repressive and conservative the 1950s were in the U.S., is that there were cracks in that homogeneous façade way before the 1960s blew it apart. The Price of Salt, for all its “explosive” content, found a major publisher fairly quickly and sold more than a million copies in the first couple of years it was out. This shouldn’t really be surprising. After all, the 1950s gave us some of our most iconic images of rebellion against conformity—Brando and Dean, early rock ‘n’ roll, the Beats going On The Road. And in the 1950s there were also networks, whole communities, of people whose lives ran against the grain.

Highsmith knew this, and wove it all into her novel. Many of her characters are vaguely bohemian, artists or would-be artists, who knowingly read James Joyce and—more significantly—Gertrude Stein. (The use of Modernism as a signifier of both hipness and queerness is one of the novel’s fetching period details, along with references to the atom bomb and a level of tobacco and alcohol consumption that makes Don Draper look abstemious. Judging from the trailers, the cigarettes and cocktails have made it into the movie, but I suspect that the winking allusions to Stein haven’t.)

The characters know about people “like that.” Therese, for all her initial naiveté, works in theater, which brings her into contact with a number of recognizable queers and allows us to think that if her career in set design takes off, she’ll never want for a community. Carol, separated from Harge, also chooses a promisingly “alternative” job selling antique furniture. She’ll probably meet lots of homosexuals in her line of work, too. These women won’t have to be alienated loners.

Furthermore, Highsmith doesn’t single out sexual oddities: the novel indicates that a lot of people are unhappy conforming to what they’re supposed to be doing, like Therese’s boyfriend Richard, who thinks he wants to be a painter but is destined to end up working for his family’s gas bottling business. The novel doesn’t pit embattled homosexuals against a punitive social order quite so much as it suggests that people doing creative work, queer or not, are generally happier than people who work as cogs in a capitalist machine.

Indeed, Therese’s conflicts—if not Carol’s—have less to do with social condemnation of her love for Carol, although that unquestionably plays a role, than with her own inability to connect her feelings to what she knows about lesbians. The predominant image of lesbians in the 1950s, purveyed by both the medical/psychological establishment and lesbians themselves, was of gender-non-conforming women, or what used to be called “congenital inverts.” At least one member of a lesbian couple was supposed to be noticeably masculine in her affect, style, and behavior.

This was a model that provided a profound sense of recognition and identity to innumerable women, and still does today. But it was, and is, of little use to women like Therese and Carol, whose erotic identity and desires both respond to conventional markers of femininity: skirts, high heels, cosmetics, perfume, carefully styled hair. For the woman like Therese who might thrill equally to the sight of herself in a beautiful dress, or the sight of another woman with lipstick and manicured fingernails, there was no language, no conceptual slot to fit herself into. As Therese tries to understand the nature of her feelings for Carol, she thinks, “She had heard about girls falling in love, and she knew what kind of people they were and what they looked like. Neither she nor Carol looked like that.” Hers was the love that not only didn’t dare speak its name, but had no idea what its name might be.

It’s hard to remember in these post-"L Word" days, but until that show came along with its fabulously dressed, long-haired, heavily made-up lesbians constantly falling into bed with one another, depictions of femme-femme relationships were rare outside of heterosexually oriented pornography. Such couples are easily mocked as conformist, assimilationist, class-privileged, and/or catering to male fantasies, and the on-screen pairing of Blanchett and Mara is probably going to provoke some of the same criticisms. But the fact is that particular permutation of desire was a potent reality for some women in 1952, as it is for some women now.

The Price of Salt was bold for its time in many ways: it didn’t condemn its lovers to suicide or send them back to their men. It suggested that queers, in certain cities and certain professions, could find friends, communities, and creative work that were fulfilling and sustaining. And it departed from the butch-femme paradigm that was standard not only in the popular conception of lesbians, but in almost all lesbian fiction before it. It tells us, in short, that even in 1952 women who fell in love with other women could break all kinds of molds, without breaking themselves.

It’s a vision of lesbian life in some ways freer and more inspiring than we, from our fortunate position in 2015, expect from the 1950s. So as people line up to see Carol (and I, for one, intend to be in that line), I hope they’ll also pick up The Price of Salt so that they can judge for themselves what Highsmith wanted to say about queerness in the 1950s. And I hope they’ll remember that, however far we’ve come since 1952, we got here only because writers like Highsmith expanded the parameters of what could be said about homosexuality. And then dedicated lesbian readers, publishing houses, and bookstores kept this work in print and built a culture and a community that changed America to the point where Todd Haynes could think about making this movie, and a big studio would back it, critics would rave about it, and audiences would—I hope—flock to it.

Erin G. Carlston lives in New Zealand, where she teaches and writes about sexuality, gender, and race in Modernist literature.